http://www.washingtonpost.com

‘ISIS’ vs. ‘ISIL’ vs. ‘Islamic State’: The political importance of a much-debated acronym

Tonight, President Obama in his State of the Union address refered to "ISIL," or the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.Here's the portion of his speech in which he refers to the terror group:

In Iraq and Syria, American leadership – including our military power – is stopping ISIL’s advance. Instead of getting dragged into another ground war in the Middle East, we are leading a broad coalition, including Arab nations, to degrade and ultimately destroy this terrorist group. We’re also supporting a moderate opposition in Syria that can help us in this effort, and assisting people everywhere who stand up to the bankrupt ideology of violent extremism. This effort will take time. It will require focus. But we will succeed. And tonight, I call on this Congress to show the world that we are united in this mission by passing a resolution to authorize the use of force against ISIL.In September, President Obama went on "Meet the Press" to talk with new host Chuck Todd. They talked at length about terrorism and the administration's plans to counter it, but they didn't couldn't quite agree on what to call the enemy.

"I'm preparing the country to make sure that we deal with a threat from ISIL," Obama said. ISIL stands for the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant. Todd followed up with, "Obviously, if you're going to defeat ISIS, you have used very much stronger language." ISIS stands for the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

Later, after the interview ended, Todd told his panel, "Obviously we refer to it at NBC News as ISIS. The Obama administration, president, says the word ISIL. The last S stands for Syria, the last L they don’t want to have stand for Syria." The insinuation is that the country Obama decided to stay out of last year is also his Voldemort, better left unnamed.

Many conservative news organizations agreed that the acronym was worth 1,000 words.

Many politicians and media organizations that have chosen ISIL rather than ISIS have said they went with the former as a paean to grammar. When you translate the Arabic name for the group of insurgents (Al-Dawla Al-Islamiya fi al-Iraq wa al-Sham) into English, many argue that using "the Levant" (a.k.a. ISIL) to describe the region is most accurate -- as this WorldViews post from June explains.

Others have interpreted this acronym choice differently. Maureen Dowd wrote in an Aug. 9 column:

It’s a bit odd that the administration is using “the Levant,” given that it conjures up a colonial association from the early 20th century, when Britain and France drew their maps, carving up Mesopotamia guided by economic gain rather than tribal allegiances. Unless it’s a nostalgic nod to a time when puppets were more malleable and grateful to their imperial overlords.The White House has often faced an army of deconstructionists whenever words come out of Obama's mouth -- and even when they don't -- and it seems a bit excessive to infer an entire foreign policy from an acronym. But politicians and media organizations all over have struggled with what to call this group of Sunni insurgents, and how their choice would be interpreted.

House Democrats last year decided after a long debate that they too would call the extremist group ISIL -- partly because ISIS was a name that first belonged to a goddess, and then to thousands of women who took said goddess's name, before a terrorist group claimed it.

ISIL might sound odd, which is why it has the virtue of not already being taken by other people. The Obama administration has been clear that the Sunni insurgents represent a serious threat, and if the group sounds like nothing you've ever heard before, both in deed and name, it's probably easier to make that sink in.

The Levant also denotes a far larger region than just Iraq and Syria. By calling the group ISIL instead of ISIS, it implies that the group is not only a serious threat, it is a large one too.

Going back to Congress: Even before House Democrats decided to go with ISIL, there was an evident partisan split on Congress on how legislators decided to refer to the group, as shown by data collected by the Sunlight Foundation.

Out of all the mentions of ISIS that have occurred during floor speeches, 86 percent have come from Republicans. Fifty-four percent of ISIL mentions have come from Democrats. However, this split could be explained by many other things -- Republicans out-talking Democrats on the Islamic State overall or the fact that Congress has had the same difficulties settling on a name as the media has.

While the government has been choosing between ISIS and ISIL, many news organizations have been making similar decisions in their style guides. The Washington Post has decided to refer to the group as the Islamic State, after the group itself declared that its ambitions outstripped Iraq and Greater Syria. Several other news organizations have also made the switch, including the Associated Press, as Poynter reported.

About a month ago ISIL changed its name, so our approach is to refer to them on first reference simply as “Islamic militants,” “jihadi fighters,” “the leading Islamic militant group fighting in Iraq (Syria), etc.” On second reference, something like “the group, which calls itself the Islamic State,” with “group” helping to make clear that it is not an internationally recognized state.The ISIL-ISIS debate continues in large part because that the Islamic State is not internationally recognized, and officials wouldn't want to recognize the existence of a state that remains an ambition of a group they hope to extinguish.

Regardless of the reasoning, the fact that the Islamic State suffers so many synonyms has probably done little more than confuse the public, which has only figured out who these Sunni insurgents are very recently. A NBC/Wall Street Journal poll from July asking for opinions on the United States' actions against the group had 40 percent of respondents saying they didn't know enough to have an opinion. A recent ABC News/Washington Post poll shows that people now seem much more informed, but no polling exists testing public opinion on ISIL or the Islamic State.

The lesson: This situation is moving so fast -- the many explainers written about ISIS v. ISIL in June are already a few steps behind -- and the Islamic State's identity is changing so rapidly that it seems futile to treat acronyms as a magnifying glass.

However, it also isn't surprising. Given the White House's caution in explaining its thinking on how to deal with the Sunni insurgents, the media hasn't had much to parse beside the one letter that differentiates the administration from many of the news outlets that cover it.

Jaime

Fuller reports on national politics for "The Fix" and Post Politics.

She worked previously as an associate editor at the American Prospect, a

political magazine based in Washington, D.C.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Islamic State |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: باقية وتتمدد (Arabic) "Bāqiyah wa-Tatamaddad" (transliteration) "Remaining and Expanding"[1][2] |

||||||

| Capital | Ar-Raqqah, Syria[3][4] 35°57′N 39°1′E |

|||||

| Government | Islamic caliphate | |||||

| - | Caliph[5] | Ibrahim[6][7] | ||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant declared | 9 April 2013[8] | ||||

| - | Caliphate declared | 29 June 2014[5] | ||||

| Time zone | Arabia Standard Time (UTC+3) | |||||

| Calling code | +963 (Syria) +964 (Iraq) |

|||||

ISIS is the successor to Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn—more commonly known as Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)—formed by Abu Musab Al Zarqawi in 2004, which took part in the Iraqi insurgency against American-led forces and their Iraqi allies following the 2003 invasion of Iraq.[60][74] During the 2003–2011 Iraq War it combined with other Sunni insurgent groups to form the Mujahideen Shura Council and consolidated further into the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI).[75][74] At its height it enjoyed a significant presence in the Iraqi governorates of Al Anbar, Nineveh, Kirkuk, most of Salah ad Din, parts of Babil, Diyala and Baghdad, and claimed Baqubah as a capital city.[76][77][78][79] However, the ISI’s violent attempts to govern its territory led to a backlash from Sunni Iraqis and other insurgent groups, which helped to propel the Awakening movement and a decline in the group.[80][74]

Under its leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, ISIS has grown significantly, gaining support in Iraq due to alleged economic and political discrimination against Arab Iraqi Sunnis, and establishing a large presence in the Syrian governorates of Ar-Raqqah, Idlib, Deir ez-Zor and Aleppo after entering the Syrian Civil War.[81][82][83]

ISIS had close links to al-Qaeda until February 2014, when, after an eight-month power struggle, al-Qaeda cut all ties with the group, reportedly for its brutality and "notorious intractability."[84][85][86]

In June 2014, ISIS had at least 4,000 fighters in its ranks in Iraq[87] who, in addition to attacks on government and military targets, have claimed responsibility for attacks that have killed thousands of civilians.[88] In August 2014, the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights claimed that the group had increased its strength to 50,000 fighters in Syria and 30,000 in Iraq.[17]

ISIS’s original aim was to establish a caliphate in the Sunni-majority regions of Iraq. Following its involvement in the Syrian Civil War, this expanded to include controlling Sunni-majority areas of Syria.[89] A caliphate was proclaimed on 29 June 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi—now known as Amir al-Mu'minin Caliph Ibrahim—was named as its caliph, and the group was renamed the Islamic State.[5][6][7]

Contents

- 1 Name and name changes

- 2 Ideology and beliefs

- 3 Goals

- 4 Territorial claims

- 5 Analysis

- 6 Propaganda and social media

- 7 Finances

- 8 Equipment

- 9 History

- 10 Human rights abuses

- 11 Timeline of events

- 12 Notable members

- 13 Designation as a terrorist organization

- 14 See also

- 15 Notes

- 16 References

- 17 Bibliography

- 18 External links

Name and name changes

The group has had a number of different names since its formation in early 2004 as Jamāʻat al-Tawḥīd wa-al-Jihād, "The Organization of Monotheism and Jihad" (JTJ).[9]In October 2004, the group's leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi swore loyalty to Osama bin Laden and changed the name of the group to Tanẓīm Qāʻidat al-Jihād fī Bilād al-Rāfidayn, "The Organization of Jihad's Base in the Country of the Two Rivers," more commonly known as "Al-Qaeda in Iraq" (AQI).[9][90] Although the group has never called itself "Al-Qaeda in Iraq", this name has frequently been used to describe it through its various incarnations.[11]

In January 2006, AQI merged with several smaller Iraqi insurgent groups under an umbrella organization called the "Mujahideen Shura Council." This was little more than a media exercise and an attempt to give the group a more Iraqi flavour and perhaps to distance al-Qaeda from some of al-Zarqawi's tactical errors, notably the 2005 bombings by AQI of three hotels in Amman.[91] Al-Zarqawi was killed in June 2006, after which the group's direction shifted again.

On 12 October 2006, the Mujahideen Shura Council joined four more insurgent factions and the representatives of a number of Iraqi Arab tribes, and together they swore the traditional Arab oath of allegiance known as Ḥilf al-Muṭayyabīn ("Oath of the Scented Ones").[b][92][93] During the ceremony, the participants swore to free Iraq's Sunnis from what they described as Shia and foreign oppression, and to further the name of Allah and restore Islam to glory.[c][92]

On 13 October 2006, the establishment of the Dawlat al-ʻIraq al-Islāmīyah, "Islamic State of Iraq" (ISI) was announced.[9][94] A cabinet was formed and Abu Abdullah al-Rashid al-Baghdadi became ISI's figurehead emir, with the real power residing with the Egyptian Abu Ayyub al-Masri.[95] The declaration was met with hostile criticism, not only from ISI's jihadist rivals in Iraq, but from leading jihadist ideologues outside the country.[96] Al-Baghdadi and al-Masri were both killed in a US–Iraqi operation in April 2010. The next leader of the ISI was Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the current leader of ISIS.

On 9 April 2013, having expanded into Syria, the group adopted the name "Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant", also known as "Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham."[97][98] The name is abbreviated as ISIS or alternately ISIL. The final "S" in the acronym ISIS stems from the Arabic word Shām (or Shaam), which in the context of global jihad refers to the Levant or Greater Syria.[99][100] ISIS was also known as al-Dawlah ("the State"), or al-Dawlat al-Islāmīyah ("the Islamic State"). These are short-forms of the name "Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham" in Arabic; it is similar to calling "the United States of America" "the States."[101]

ISIS's detractors, particularly in Syria, refer to the group as "Da'ish" or "Daesh", (داعش), a term that is based on an acronym formed from the letters of the name in Arabic, al-Dawla al-Islamiya fi Iraq wa al-Sham.[102][103] The group considers the term derogatory and reportedly uses flogging as a punishment for people who use the acronym in ISIS-controlled areas.[104][105]

On 14 May 2014, the United States Department of State announced its decision to use "Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant" (ISIL) as the group's primary name.[103] The debate over which acronym should be used to designate the group, ISIL or ISIS, has been discussed by several commentators.[100][101] Ishaan Tharoor from The Washington Post concluded: "In the larger battlefield of copy style controversies, the distinction between ISIS or ISIL is not so great."[101]

On 29 June 2014, the establishment of a new caliphate was announced, with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi named as its caliph, and the group formally changed its name to the "Islamic State".[5][106][d]

In late August 2014, a leading Islamic authority, Dar al-Ifta al-Misriyyah, recently advised muslims to refer to the group as QSIS; which stands for al-Qaeda Separatists in Iraq and Syria, due to the militant group's un-islamic character.[108]

Ideology and beliefs

ISIS is an extremist group that follows al-Qaeda's hard-line ideology and adheres to global jihadist principles.[109][110] Like al-Qaeda and many other modern-day jihadist groups, ISIS emerged from the ideology of the Muslim Brotherhood, the world’s first Islamist group dating back to the late 1920s in Egypt.[111] ISIS follows an extreme anti-Western interpretation of Islam, promotes religious violence and regards those who do not agree with its interpretations as infidels and apostates. Concurrently, ISIS—now IS—aims to establish a Salafist-orientated Islamist state in Iraq, Syria and other parts of the Levant.[110]ISIS's ideology originates in the branch of modern Islam that aims to return to the early days of Islam, rejecting later "innovations" in the religion which it believes corrupt its original spirit. It condemns later caliphates and the Ottoman empire for deviating from what it calls pure Islam and hence has been attempting to establish its own caliphate.[112] However, there are some Sunni commentators, Zaid Hamid, for example, and even Salafi and jihadi muftis such as Adnan al-Aroor and Abu Basir al-Tartusi, who say that ISIS and related terrorist groups are not Sunnis at all, but Kharijite heretics serving an imperial anti-Islamic agenda.[113][114][115][116]

Salafists such as ISIS believe that only a legitimate authority can undertake the leadership of jihad, and that the first priority over other areas of combat, such as fighting against non-Muslim countries, is the purification of Islamic society. For example, when it comes to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, since ISIS regards the Palestinian Sunni group Hamas as apostates who have no legitimate authority to lead jihad, it regards fighting Hamas as the first step toward confrontation with Israel.[117][118]

Goals

From its beginnings the establishment of a pure Islamic state has been one of the group's main goals.[119] According to journalist Sarah Birke, one of the "significant differences" between Al-Nusra Front and ISIS is that ISIS "tends to be more focused on establishing its own rule on conquered territory". While both groups share the ambition to build an Islamic state, ISIS is "far more ruthless ... carrying out sectarian attacks and imposing sharia law immediately".[120] ISIS finally achieved its goal on 29 June 2014, when it removed "Iraq and the Levant" from its name, began to refer to itself as the Islamic State, and declared the territory which it occupied in Iraq and Syria a new caliphate.[5]In mid-2014, the group released a video entitled "The End of Sykes–Picot" featuring an English-speaking Chilean national named Abu Safiyya. The video announced the group's intention to eliminate all modern borders between Islamic Middle Eastern countries; this was a reference to the borders set by the Sykes–Picot Agreement during World War I.[121][122]

Territorial claims

On 13 October 2006, the group announced the establishment of the Islamic State of Iraq, which claimed authority over the Iraqi governorates of Baghdad, Anbar, Diyala, Kirkuk, Salah al-Din, Nineveh, and parts of Babil.[94] Following the 2013 expansion of the group into Syria and the announcement of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, the number of wilayah—provinces—which it claimed increased to 16. In addition to the seven Iraqi wilayah, the Syrian divisions, largely lying along existing provincial boundaries, are Al Barakah, Al Kheir, Ar-Raqqah, Al Badiya, Halab, Idlib, Hama, Damascus and the Coast.[123] In Syria, ISIS's seat of power is in Ar-Raqqah Governorate. Top ISIS leaders, including Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, are known to have visited its provincial capital, Ar-Raqqah.[123]During the Iraq conflict in 2014 the group expanded the areas under its control even further, and concerns have now been expressed about the capability of the IS to govern the territories it has conquered.[124]

Analysis

After significant setbacks for the group during the latter stages of the coalition forces' presence in Iraq, by late 2012 it was thought to have renewed its strength and more than doubled the number of its members to about 2,500,[125] and since its formation in April 2013, ISIS has grown rapidly in strength and influence in Iraq and Syria. Analysts have underlined the deliberate inflammation of sectarian conflict between Iraqi Shias and Sunnis during the Iraq War by various Sunni and Shiite actors as the root cause of ISIS's rise. The post-invasion policies of the international coalition forces have also been cited as a factor, with Fanar Haddad, a research fellow at the National University of Singapore's Middle East Institute, blaming the coalition forces during the Iraq War for "enshrining identity politics as the key marker of Iraqi politics".[126] ISIS's violence is directed particularly against Shia Muslims and indigenous Assyrian/Chaldean/Syriac Christians and Armenian Christians.[127] In June 2014, The Economist reported that "ISIS may have up to 6,000 fighters in Iraq and 3,000–5,000 in Syria, including perhaps 3,000 foreigners; nearly a thousand are reported to hail from Chechnya and perhaps 500 or so more from France, Britain and elsewhere in Europe".[128] Chechen fighter Abu Omar al-Shishani, for example, was made commander of the northern sector of ISIS in Syria in 2013.[129][130]By 2014, ISIS was increasingly being viewed as a militia rather than a terrorist group by some organizations.[131] As major Iraqi cities fell to al-Baghdadi's cohorts in June, Jessica Lewis, a former US army intelligence officer at the Institute for the Study of War, described ISIS as "not a terrorism problem anymore", but rather "an army on the move in Iraq and Syria, and they are taking terrain. They have shadow governments in and around Baghdad, and they have an aspirational goal to govern. I don't know whether they want to control Baghdad, or if they want to destroy the functions of the Iraqi state, but either way the outcome will be disastrous for Iraq." Lewis has called ISIS "an advanced military leadership". She said, "They have incredible command and control and they have a sophisticated reporting mechanism from the field that can relay tactics and directives up and down the line. They are well-financed, and they have big sources of manpower, not just the foreign fighters, but also prisoner escapees."[131]

According to the Institute for the Study of War, ISIS's annual reports reveal a metrics-driven military command, which is "a strong indication of a unified, coherent leadership structure that commands from the top down".[132] Middle East Forum's Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi said, "They are highly skilled in urban guerrilla warfare while the new Iraqi Army simply lacks tactical competence."[131] Seasoned observers point to systemic corruption within the Iraq Army, it being little more than a system of patronage, and have attributed to this its spectacular collapse as ISIS and its allies took over large swaths of Iraq in June 2014.[133] On 21 August 2014, in response to a question asking whether ISIS posed a similar threat to al-Qaeda prior to the September 11th attacks[134] United States Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel stated: "(ISIS) is as sophisticated and well-funded as any group that we have seen. They're beyond just a terrorist group".[135]

Hillary Clinton stated: "The failure to help build up a credible fighting force of the people who were the originators of the protests against Assad—there were Islamists, there were secularists, there was everything in the middle—the failure to do that left a big vacuum, which the jihadists have now filled."[136]

ISIS runs a soft-power program in the areas under its control in Iraq and Syria, which includes social services, religious lectures and da'wah—proselytizing—to local populations. It also performs civil tasks such as repairing roads and maintaining the electricity supply.[137]

Propaganda and social media

The group is also known for its effective use of propaganda.[138] In November 2006, shortly after the creation of the Islamic State of Iraq, the group established the al-Furqan Institute for Media Production, which produced CDs, DVDs, posters, pamphlets, and web-related propaganda products.[139] ISIS's main media outlet is the I'tisaam Media Foundation,[140] which was formed in March 2013 and distributes through the Global Islamic Media Front (GIMF).[141] In 2014, ISIS established the Al Hayat Media Center, which targets a Western audience and produces material in English, German, Russian and French.[142][143] In 2014 it also launched the Ajnad Media Foundation, which releases jihadist audio chants.[144]In July 2014, ISIS began publishing a digital magazine called Dabiq in multiple languages, including English. According to the magazine, its name is taken from the town in northern Syria, which is mentioned in a hadith about Armageddon.[145] Harleen K. Gambhir, of the Institute for the Study of War, found that while al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula's Inspire magazine focused on encouraging its readers to carry out lone-wolf attacks on the West, Dabiq is more concerned with establishing the religious legitimacy of ISIS and its self-proclaimed caliphate, and encouraging Muslims to emigrate there.[146]

ISIS's use of social media has been described by one expert as "probably more sophisticated than [that of] most US companies".[147][148] It regularly takes advantage of social media, particularly Twitter, to distribute its message by organizing hashtag campaigns, encouraging Tweets on popular hashtags, and utilizing software applications that enable ISIS propaganda to be distributed to its supporters' accounts.[149] Another comment is that "ISIS puts more emphasis on social media than other jihadi groups. ... They have a very coordinated social media presence."[150] Although ISIS's social media feeds on Twitter are regularly shut down, it frequently recreates them, maintaining a strong online presence. The group has attempted to branch out into alternate social media sites, such as Quitter, Friendica and Diaspora; Quitter and Friendica, however, almost immediately removed ISIS's presence from their sites.[151]

Egyptian and Lebanese media and politicians, as well as Facebook users, have spread the false claim that in her book Hard Choices Hillary Clinton stated that she created ISIS.[152] Fake quotes supposedly from Hard Choices have been used to support this false claim.[152]

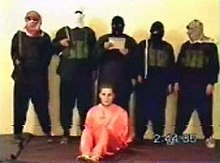

A pivotal moment[citation needed] occurred on 19 August 2014, when militants posted a propaganda video of the beheading of US photojournalist James Foley on the Internet; it claimed that the killing had been carried out in revenge for the US bombing of ISIS targets.[153] The video promised that a second captured US journalist Steven Sotloff would be killed next if the airstrikes continued.[154]

Finances

A study of 200 documents—personal letters, expense reports and membership rosters—captured from Al-Qaeda in Iraq and the Islamic State of Iraq was carried out by the RAND Corporation in 2014.[155] It found that from 2005 until 2010, outside donations amounted to only 5% of the group’s operating budgets, with the rest being raised within Iraq.[155] In the time-period studied, cells were required to send up to 20% of the income generated from kidnapping, extortion rackets and other activities to the next level of the group's leadership. Higher-ranking commanders would then redistribute the funds to provincial or local cells that were in difficulties or needed money to conduct attacks.[155] The records show that the Islamic State of Iraq was dependent on members from Mosul for cash, which the leadership used to provide additional funds to struggling militants in Diyala, Salahuddin and Baghdad.[155]In mid-2014, Iraqi intelligence extracted information from an ISIS operative which revealed that the organization had assets worth US$2 billion,[156] making it the richest jihadist group in the world.[157] About three quarters of this sum is said to be represented by assets seized after the group captured Mosul in June 2014; this includes possibly up to US$429 million looted from Mosul's central bank, along with additional millions and a large quantity of gold bullion stolen from a number of other banks in Mosul.[158][159] However, doubt was later cast on whether ISIS was able to retrieve anywhere near that sum from the central bank,[160] and even on whether the bank robberies had actually occurred.[161]

ISIS has routinely practised extortion, by demanding money from truck drivers and threatening to blow up businesses, for example. Robbing banks and gold shops has been another source of income.[70] The group is widely reported as receiving funding from private donors in the Gulf states,[162][163] and both Iran and Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki have accused Saudi Arabia and Qatar of funding ISIS,[164][165][166][167] although there is reportedly no evidence that this is the case.[167][168][169][170]

The group is also believed to receive considerable funds from its operations in Eastern Syria, where it has commandeered oilfields and engages in smuggling out raw materials and archaeological artifacts.[171][172] ISIS also generates revenue from producing crude oil and selling electric power in northern Syria. Some of this electricity is reportedly sold back to the Syrian government.[173]

Since 2012, ISIS has produced annual reports giving numerical information on its operations, somewhat in the style of corporate reports, seemingly in a bid to encourage potential donors.[147][174]

Equipment

The most common weapons used against US and other Coalition forces during the Iraq insurgency were those taken from Saddam Hussein’s weapon stockpiles around the country, these included AKM variant assault rifles, PK machine guns and RPG-7s.[175] ISIS has been able to strengthen its military capability by capturing large quantities and varieties of weaponry during the Syrian Civil War and Post-U.S. Iraq insurgency. These weapons seizures have improved the group's capacity to carry out successful subsequent operations and obtain more equipment.[176] Weaponry that ISIS has reportedly captured and employed include SA-7[177] and Stinger[178] surface-to-air missiles, M79 Osa, HJ-8[179] and AT-4 Spigot[177] anti-tank weapons, Type 59 field guns[179] and M198 howitzers,[180] Humvees, T-54/55 and T-72 main battle tanks,[179] M1117 armoured cars,[181] truck mounted DShK guns,[177] ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft guns,[182][183] BM-21 Grad multiple rocket launchers[176] and at least one Scud missile.[184]When ISIS captured Mosul Airport in June 2014, it seized a number of UH-60 Blackhawk helicopters and cargo planes that were stationed there.[185][186] However, according to Peter Beaumont of The Guardian, it seemed unlikely that ISIS would be able to deploy them.[187]

ISIS captured nuclear materials from Mosul University in July 2014. In a letter to UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, Iraq's UN Ambassador Mohamed Ali Alhakim said that the materials had been kept at the university and "can be used in manufacturing weapons of mass destruction". Nuclear experts regarded the threat as insignificant. International Atomic Energy Agency spokeswoman Gill Tudor said that the seized materials were "low grade and would not present a significant safety, security or nuclear proliferation risk".[188][189]

History

As Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (1999–2004)

Origins

Jama'at al-Tawhid wal-Jihad (abrreviated JTJ or shortened to Tawhid and Jihad, Tawhid wal-Jihad, sometimes Tawhid al-Jihad, Al Tawhid or Tawhid) was started in 1999 by Abu Musab al-Zarqawi and a combination of foreigners and local Islamist sympathizers.[74] Al-Zarqawi was a Jordanian Salafi Jihadist who had traveled to Afghanistan to fight in the Soviet-Afghan War, but he arrived after the departure of the Soviet troops and soon returned to his homeland. He eventually returned to Afghanistan, running an Islamic militant training camp near Herat.Al-Zarqawi started the network with the intention of overthrowing the Kingdom of Jordan, which he considered to be un-Islamic according to the four schools of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence. For this purpose he developed numerous contacts and affiliates in several countries. Although it has not been verified, his network may have been involved in the late 1999 plot to bomb the Millennium celebrations in the United States and Jordan. However, al-Zarqawi's operatives were responsible for the assassination of US diplomat Laurence Foley in Jordan in 2002.[190]

Following the US-led invasion of Afghanistan, al-Zarqawi moved westward into Iraq, where he reportedly received medical treatment in Baghdad for an injured leg. It is believed that he developed extensive ties in Iraq with Ansar al-Islam ("Partisans of Islam"), a Kurdish Islamic militant group based in the extreme northeast of the country. Ansar allegedly had ties to Iraqi Intelligence; Saddam Hussein's motivation would have been to use Ansar as a surrogate force to repress secular Kurds fighting for the independence of Kurdistan.[191] In January 2003, Ansar's founder Mullah Krekar denied any connection with Saddam's government.[192]

The consensus of intelligence officials has since been that there were no links whatsoever between al-Zarqawi and Saddam, and that Saddam viewed Ansar al-Islam "as a threat to the regime"[193] and his intelligence officials were spying on the group. The 2006 Senate Report on Pre-war Intelligence on Iraq concluded: "Postwar information indicates that Saddam Hussein attempted, unsuccessfully, to locate and capture al-Zarqawi and that the regime did not have a relationship with, harbor, or turn a blind eye toward al-Zarqawi."[193] According to Michael Weiss, Ansar entered Iraqi Kurdistan through Iran as part of Iran's covert attempts to destabilize Saddam's government.[194]

Following the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, JTJ developed into an expanding militant network for the purpose of resisting the coalition occupation forces and their Iraqi allies. It included some of the remnants of Ansar al-Islam and a growing number of foreign fighters. Many foreign fighters arriving in Iraq were initially not associated with the group, but once they were in the country they became dependent on al-Zarqawi's local contacts.[195]

Goals and tactics

The stated goals of JTJ were: (i) to force a withdrawal of coalition forces from Iraq; (ii) to topple the Iraqi interim government; (iii) to assassinate collaborators with the occupation regime; (iv) to remove the Shia population and defeat its militias because of its death-squad activities; and (v) to establish subsequently a pure Islamic state.[119]JTJ differed considerably from the other early Iraqi insurgent groups in its tactics. Rather than using only conventional weapons and guerrilla tactics in ambushes against the US and coalition forces, it relied heavily on suicide bombings, often using car bombs. It targeted a wide variety of groups, especially the Iraqi Security Forces and those facilitating the occupation. Groups of workers who have been targeted by JTJ include Iraqi interim officials, Iraqi Shia and Kurdish political and religious figures, the country's Shia Muslim civilians, foreign civilian contractors, and United Nations and humanitarian workers.[195] Al-Zarqawi's militants are also known to have used a wide variety of other tactics, including targeted kidnappings, the planting of improvised explosive devices, and mortar attacks. Beginning in late June 2004, JTJ implemented urban guerrilla-style attacks using rocket-propelled grenades and small arms. They also gained worldwide notoriety for beheading Iraqi and foreign hostages and distributing video recordings of these acts on the Internet.

Activities

The group took either direct responsibility or the blame for many of the early Iraqi insurgent attacks, including the series of high-profile bombings in August 2003, which killed 17 people at the Jordanian embassy in Baghdad,[195] 23 people, including the chief of the United Nations Mission to Iraq Sérgio Vieira de Mello, at the UN headquarters in Baghdad,[195] and at least 86 people, including Ayatollah Sayed Mohammed Baqir al-Hakim, in the Imam Ali Mosque bombing in Najaf.[198] Included here is the November truck bombing, which killed 27 people, mostly Italian paramilitary policemen, at the Italian base in Nasiriyah.[195]

The attacks connected with the group in 2004 include the series of bombings in Baghdad and Karbala which killed 178 people during the holy Day of Ashura in March;[199] the failed plot in April to explode chemical bombs in Amman, Jordan, which was said to have been financed by al-Zarqawi's network;[200] a series of suicide boat bombings of the oil pumping stations in the Persian Gulf in April, for which al-Zarqawi took responsibility in a statement published by the Muntada al-Ansar Islamist website; the May car bomb assassination of Iraqi Governing Council president Ezzedine Salim at the entrance to the Green Zone in Baghdad;[201] the June suicide car bombing in Baghdad which killed 35 civilians;[202] and the September car bomb which killed 47 police recruits and civilians on Haifa Street in Baghdad.[203]

As Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn (2004–2006)

Goals and umbrella organizations

See also: Mujahideen Shura Council (Iraq)

In a letter to Ayman al-Zawahiri in July 2005, al-Zarqawi outlined a four-stage plan to expand the Iraq War, which included expelling US forces from Iraq, establishing an Islamic authority—a caliphate—spreading the conflict to Iraq's secular neighbors, and engaging in the Arab–Israeli conflict.[197]

The affiliated groups were linked to regional attacks outside Iraq

which were consistent with their stated plan, one example being the 2005

Sharm al-Sheikh bombings in Egypt, which killed 88 people, many of them foreign tourists.In January 2006, Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)—the name by which Tanzim Qaidat al-Jihad fi Bilad al-Rafidayn was more commonly known—created an umbrella organization called the Mujahideen Shura Council (MSC), in an attempt to unify Sunni insurgents in Iraq. Its efforts to recruit Iraqi Sunni nationalists and secular groups were undermined by the violent tactics it used against civilians and its extreme Islamic fundamentalist doctrine.[204] Because of these impediments, the attempt was largely unsuccessful.[205]

AQI attributed its attacks to the MSC until mid-October 2006, when Abu Ayyub al-Masri declared the formation of the self-styled Islamic State of Iraq (ISI). This was another front which included the Shura Council factions. AQI then began attributing its attacks to the ISI.[206] According to a study compiled by US intelligence agencies, the ISI had plans to seize power and turn the country into a Sunni Islamic state.[207]

As Islamic State of Iraq (2006–2013)

Strength and activity

In 2007, some observers and scholars suggested that the threat posed by AQI was being exaggerated and that a "heavy focus on al-Qaeda obscures a much more complicated situation on the ground".[212][213] According to the July 2007 National Intelligence Estimate and the Defense Intelligence Agency reports, AQI accounted for 15% percent of attacks in Iraq. However, the Congressional Research Service noted in its September 2007 report that attacks from al-Qaeda were less than 2% of the violence in Iraq. It criticized the Bush administration's statistics, noting that its false reporting of insurgency attacks as AQI attacks had increased since the surge operations began in 2007.[208][214] In March 2007, the US-sponsored Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty analyzed AQI attacks for that month and concluded that the group had taken credit for 43 out of 439 attacks on Iraqi security forces and Shia militias, and 17 out of 357 attacks on US troops.[208]

According to the 2006 US Government report, this group was most clearly associated with foreign jihadist cells operating in Iraq and had specifically targeted international forces and Iraqi citizens; most of Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)'s operatives were not Iraqi, but were coming through a series of safe houses, the largest of which was on the Iraq-Syrian border. AQI's operations were predominately Iraq-based, but the United States Department of State alleged that the group maintained an extensive logistical network throughout the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia and Europe.[215] In a June 2008 CNN special report, Al-Qaeda in Iraq was called "a well-oiled ... organization ... almost as pedantically bureaucratic as was Saddam Hussein's Ba'ath Party", collecting new execution videos long after they stopped publicising them, and having a network of spies even in the US military bases. According to the report, Iraqis—many of them former members of Hussein's secret services—were now effectively running Al-Qaeda in Iraq, with "foreign fighters' roles" seeming to be "mostly relegated to the cannon fodder of suicide attacks", although the organization's top leadership was still dominated by non-Iraqis.[216]

Rise and decline of Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI)

The group officially pledged allegiance to Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda network in a letter in October 2004.[18][217][218] That same month, the group, now popularly referred to as "Al-Qaeda in Iraq" (AQI), kidnapped and killed Japanese citizen Shosei Koda. In November, al-Zarqawi's network was the main target of the US Operation Phantom Fury in Fallujah, but its leadership managed to escape the American siege and subsequent storming of the city. In December, in two of its many sectarian attacks, AQI bombed a Shia funeral procession in Najaf and the main bus station in nearby Karbala, killing at least 60 people in those two holy cities of Shia Islam. The group also reportedly took responsibility for the 30 September 2004 Baghdad bombing which killed 41 people, mostly children.[201]In 2005, AQI largely focused on executing high-profile and coordinated suicide attacks, claiming responsibility for numerous attacks which were primarily aimed at Iraqi administrators. The group launched attacks on voters during the Iraqi legislative election in January, a combined suicide and conventional attack on the Abu Ghraib prison in April, and coordinated suicide attacks outside the Sheraton Ishtar and Palestine Hotel in Baghdad in October.[197] In July, AQI claimed responsibility for the kidnapping and execution of Ihab Al-Sherif, Egypt's envoy to Iraq.[219][220] Also in July, a three-day series of suicide attacks, including the Musayyib marketplace bombing, left at least 150 people dead.[221] Al-Zarqawi claimed responsibility for a single-day series of more than a dozen bombings in Baghdad in September, including a bomb attack on 14 September which killed about 160 people, most of whom were unemployed Shia workers.[222] They claimed responsibility for a series of mosque bombings in the same month in the city of Khanaqin, which killed at least 74 people.[223]

The attacks blamed on or claimed by AQI continued to increase in 2006 (see also the list of major resistance attacks in Iraq).[206] In one of the incidents, two US soldiers—Thomas Lowell Tucker and Kristian Menchaca—were captured, tortured and beheaded by the ISI. In another, four Russian embassy officials were abducted and subsequently killed. Iraq's al-Qaeda and its umbrella groups were blamed for multiple attacks targeting the country's Shia population, some of which AQI claimed responsibility for. The US claimed without verification that the group was at least one of the forces behind the wave of chlorine bombings in Iraq, which affected hundreds of people, albeit with few fatalities, after a series of crude chemical warfare attacks between late 2006 and mid-2007.[224] During 2006, several key members of AQI were killed or captured by American and allied forces. This included al-Zarqawi himself, killed on 7 June 2006, his spiritual adviser Sheik Abd-Al-Rahman, and the alleged "number two" deputy leader, Hamid Juma Faris Jouri al-Saeedi. The group's leadership was then assumed by a man called Abu Hamza al-Muhajir,[225] who in reality was the Egyptian militant Abu Ayyub al-Masri.[226]

By late 2007, violent and indiscriminate attacks directed by rogue AQI elements against Iraqi civilians had severely damaged their image and caused loss of support among the population, thus isolating the group. In a major blow to AQI, many former Sunni militants who had previously fought alongside the group started to work with the American forces (see also below). The US troops surge supplied the military with more manpower for operations targeting the group, resulting in dozens of high-level AQI members being captured or killed.[227] Al-Qaeda seemed to have lost its foothold in Iraq and appeared to be severely crippled.[228] Accordingly, the bounty issued for al-Masri was eventually cut from $5 million to $100,000 in April 2008.[229]

As of 2008, a series of US and Iraqi offensives managed to drive out the AQI-aligned insurgents from their former safe havens, such as the Diyala and Al Anbar governorates and the embattled capital of Baghdad, to the area of the northern city of Mosul, the latest of the Iraq War's major battlegrounds.[229] The struggle for control of Ninawa Governorate—the Ninawa campaign—was launched in January 2008 by US and Iraqi forces as part of the large-scale Operation Phantom Phoenix, which was aimed at combating al-Qaeda activity in and around Mosul, and finishing off the network's remnants in central Iraq that had escaped Operation Phantom Thunder in 2007. In Baghdad a pet market was bombed in February 2008 and a shopping centre was bombed in March 2008, killing at least 98 and 68 people respectively; AQI were the suspected perpetrators.

Resisting established sectarian violence

Attacks against militiamen often targeted the Iraqi Shia majority in an attempt to incite sectarian violence.[231] Al-Zarqawi purportedly declared an all-out war on Shias[222] while claiming responsibility for the Shia mosque bombings.[223] The same month, a letter allegedly written by al-Zawahiri—later rejected as a "fake" by the AQI—appeared to question the insurgents' tactic of indiscriminately attacking Shias in Iraq.[232] In a video that appeared in December 2007, al-Zawahiri defended the AQI, but distanced himself from the crimes against civilians committed by "hypocrites and traitors" that he said existed among its ranks.[233]US and Iraqi officials accused the AQI of trying to slide Iraq into a full-scale civil war between Iraq's majority Shia and minority Sunni Arabs via an orchestrated campaign of militiamen massacres and a number of provocative attacks against high-profile religious targets.[234] With attacks purportedly mounted by the AQI such as the Imam Ali Mosque bombing in 2003, the Day of Ashura bombings and Karbala and Najaf bombings in 2004, the first al-Askari Mosque bombing in Samarra in 2006, the deadly single-day series of bombings in November 2006 in which at least 215 people were killed in Baghdad's Shia district of Sadr City, and the second al-Askari bombing in 2007, the AQI provoked Shia militias to unleash a wave of retaliatory attacks. The result was a plague of death squad-style killings and a spiral into further sectarian violence, which escalated in 2006 and brought Iraq to the brink of violent anarchy in 2007.[205] In 2008, sectarian bombings blamed on al-Qaeda killed at least 42 people at the Imam Husayn Shrine in Karbala in March and at least 51 people at a bus stop in Baghdad in June.

Operations outside Iraq and other activities

On 3 December 2004, AQI attempted to blow up an Iraqi–Jordanian border crossing, but failed to do so. In 2006, a Jordanian court sentenced to death al-Zarqawi in absentia and two of his associates for their involvement in the plot.[235] AQI increased its presence outside Iraq by claiming credit for three attacks in 2005. In the most deadly of these attacks, suicide bombs killed 60 people in Amman, Jordan on 9 November 2005.[236] They claimed responsibility for the rocket attacks that narrowly missed the USS Kearsarge and USS Ashland in Jordan, which also targeted the city of Eilat in Israel, and for the firing of several rockets into Israel from Lebanon in December 2005.[197]The Lebanese-Palestinian militant group Fatah al-Islam, which was defeated by Lebanese government forces during the 2007 Lebanon conflict, was linked to AQI and led by al-Zarqawi's former companion who had fought alongside him in Iraq.[237] The group may have been linked to the little-known group called "Tawhid and Jihad in Syria",[238] and may have influenced the Palestinian resistance group in Gaza called "Tawhid and Jihad Brigades", better known as the Army of Islam.[239]

American officials believed that Al-Qaeda in Iraq had conducted bomb attacks against Syrian government forces.[240][241][242] Al-Nusra Front, another al-Qaeda-inspired group, claimed responsibility for attacks inside Syria, and Iraqi Foreign Minister Hoshyar Zebari said that Al-Qaeda in Iraq members were going to Syria, where the militants had previously received support and weapons.[243]

Conflicts with other groups

See also: Awakening movements in Iraq and Islamic Army-al-Qaeda conflict

The first reports of a split and even armed clashes between Al-Qaeda in Iraq and other Sunni groups date back to 2005.[244][245] In the summer of 2006, local Sunni tribes and insurgent groups, including the prominent Islamist-nationalist group Islamic Army in Iraq (IAI), began to speak of their dissatisfaction with al-Qaeda and its tactics,[246]

openly criticizing the foreign fighters for their deliberate targeting

of Iraqi civilians. In September 2006, 30 Anbar tribes formed their own

local alliance called the Anbar Salvation Council (ASC), which was directed specifically at countering al-Qaeda-allied terrorist forces in the province,[247][248] and they openly sided with the government and the US troops.[249]By the beginning of 2007, Sunni tribes and nationalist insurgents had begun battling with their former allies in AQI in order to retake control of their communities.[250] In early 2007, forces allied to Al-Qaeda in Iraq committed a series of attacks on Sunnis critical of the group, including the February 2007 attack in which scores of people were killed when a truck bomb exploded near a Sunni mosque in Fallujah.[251] Al-Qaeda supposedly played a role in the assassination of the leader of the Anbar-based insurgent group 1920 Revolution Brigade, the military wing of the Islamic Resistance Movement.[252] In April 2007, the IAI spokesman accused the ISI of killing at least 30 members of the IAI, as well as members of the Jamaat Ansar al-Sunna and Mujahideen Army insurgent groups, and called on Osama bin Laden to intervene personally to rein in Al-Qaeda in Iraq.[230][253] The following month, the government announced that AQI leader al-Masri had been killed by ASC fighters.[226][234] Four days later, AQI released an audio tape in which a man claiming to be al-Masri warned Sunnis not to take part in the political process; he also said that reports of internal fighting between Sunni militia groups were "lies and fabrications".[254] Later in May, the US forces announced the release of dozens of Iraqis who were tortured by AQI as a part of the group's intimidation campaign.[255]

By June 2007, the growing hostility between foreign-influenced jihadists and Sunni nationalists had led to open gun battles between the groups in Baghdad.[256][257] The Islamic Army soon reached a ceasefire agreement with AQI, but refused to sign on to the ISI.[258] There were reports that Hamas of Iraq insurgents were involved in assisting US troops in their Diyala Governorate operations against Al-Qaeda in August 2007. In September 2007, AQI claimed responsibility for the assassination of three people including the prominent Sunni sheikh Abdul Sattar Abu Risha, leader of the Anbar "Awakening council". That same month, a suicide attack on a mosque in the city of Baqubah killed 28 people, including members of Hamas of Iraq and the 1920 Revolution Brigade, during a meeting at the mosque between tribal and guerilla leaders and the police.[259] Meanwhile, the US military began arming moderate insurgent factions when they promised to fight Al-Qaeda in Iraq instead of the Americans.[260]

By December 2007, the strength of the "Awakening" movement irregulars—also called "Concerned Local Citizens" and "Sons of Iraq"—was estimated at 65,000–80,000 fighters.[261] Many of them were former insurgents, including alienated former AQI supporters, and they were now being armed and paid by the Americans specifically to combat al-Qaeda's presence in Iraq. As of July 2007, this highly controversial strategy proved to be effective in helping to secure the Sunni districts of Baghdad and the other hotspots of central Iraq, and to root out the al-Qaeda-aligned militants.

By 2008, the ISI was describing itself as being in a state of "extraordinary crisis",[262] which was attributable to a number of factors,[263] notably the Anbar Awakening, but a few years later the group was greatly re-energised by the Syrian Civil War.

Transformation and resurgence

In early 2009, US forces began pulling out of cities across the country, turning over the task of maintaining security to the Iraqi Army, the Iraqi Police Service and their paramilitary allies. Experts and many Iraqis were worried that in the absence of US soldiers the ISI might resurface and attempt mass-casualty attacks to destabilize the country.[264] There was indeed a spike in the number of suicide attacks,[265] and through mid- and late 2009, the ISI rebounded in strength and appeared to be launching a concerted effort to cripple the Iraqi government.[266] During August and October 2009, the ISI claimed responsibility for four bombings targeting five government buildings in Baghdad, including attacks that killed 101 at the ministries of Foreign Affairs and Finance in August and 155 at the Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Municipalities and Public Works in September; these were the deadliest attacks directed at the new government in more than six years of war. These attacks represented a shift away from the group's previous efforts to incite sectarian violence, although a series of suicide attacks in April targeted mainly Iranian Shia pilgrims, killing 76, and in June, a mosque bombing in Taza killed at least 73 Shias from the Turkmen ethnic minority.In late 2009, the commander of the US forces in Iraq, General Ray Odierno, stated that the ISI "has transformed significantly in the last two years. What once was dominated by foreign individuals has now become more and more dominated by Iraqi citizens". Odierno's comments reinforced accusations by the government of Nouri al-Maliki that al-Qaeda and ex-Ba'athists were working together to undermine improved security and sabotage the planned Iraqi parliamentary elections in 2010.[267] On 18 April 2010, the ISI’s two top leaders, Abu Ayyub al-Masri and Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, were killed in a joint US-Iraqi raid near Tikrit.[268] In a press conference in June 2010, General Odierno reported that 80% of the ISI’s top 42 leaders, including recruiters and financiers, had been killed or captured, with only eight remaining at large. He said that they had been cut off from Al Qaeda's leadership in Pakistan, and that improved intelligence had enabled the successful mission in April that led to the killing of al-Masri and al-Baghdadi; in addition, the number of attacks and casualty figures in Iraq for the first five months of 2010 were the lowest since 2003.[269][270][271] In May 2011, the Islamic State of Iraq's "emir of Baghdad" Huthaifa al-Batawi, captured during the crackdown after the 2010 Baghdad church attack in which 68 people died, was killed during an attempted prison break, during which an Iraqi general and several others were also killed.[272][273]

On 16 May 2010, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was appointed the new leader of the Islamic State of Iraq;[274] he had previously been the general supervisor of the group's provincial sharia committees and a member of its senior consultative council.[275] Al-Baghdadi replenished the group's leadership, many of whom had been killed or captured, by appointing former Ba'athist military and intelligence officers who had served during the Saddam Hussein regime. Among these was a former army officer known as Haji Bakr, who became the group's overall military commander in charge of overseeing operations.[276]

In July 2012, al-Baghdadi’s first audio statement was released online. In this he announced that the group was returning to the former strongholds that US troops and their Sunni allies had driven them from prior to the withdrawal of US troops.[277] He also declared the start of a new offensive in Iraq called Breaking the Walls which would focus on freeing members of the group held in Iraqi prisons.[277] Violence in Iraq began to escalate that month, and in the following year the group carried out 24 waves of VBIED attacks and eight prison breaks. By July 2013, monthly fatalities had exceeded 1,000 for the first time since April 2008.[278] The Breaking the Walls campaign culminated in July 2013, with the group carrying out simultaneous raids on Taji and Abu Ghraib prison, freeing more than 500 prisoners, many of them veterans of the Iraqi insurgency.[278][279]

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi was declared a Specially Designated Global Terrorist on 4 October 2011 by the US State Department, with an announced reward of US$10 million for information leading to his capture or death.[280]

As Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (2013–2014)

Declaration and dispute with Al-Nusra Front

In March 2011, protests began in Syria against the government of Bashar al-Assad. In the following month violence between demonstrators and security forces lead to a gradual militarisation of the conflict.[281] In August 2011, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi began sending Syrian and Iraqi ISI members, experienced in guerilla warfare, across the border into Syria to establish an organisation inside the country. Lead by a Syrian known as Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, the group began to recruit fighters and establish cells throughout the country.[282][283] On 23 January 2012, the group announced its formation as Jabhat al-Nusra l’Ahl as-Sham, more commonly known as al-Nusra Front. Nusra rapidly expanded into a capable fighting force with a level of popular support among opposition supporters in Syria.[282]In April 2013, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi released an audio statement in which he announced that Al-Nusra Front—also known as Jabhat al-Nusra—had been established, financed and supported by the Islamic State of Iraq.[284] Al-Baghdadi declared that the two groups were merging under the name "Islamic State of Iraq and Al-Sham".[285] The leader of Al-Nusra Front, Abu Muhammad al-Jawlani, issued a statement denying the merger and complaining that neither he nor anyone else in Al-Nusra's leadership had been consulted about it.[286] In June 2013, Al Jazeera reported that it had obtained a letter written by al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, addressed to both leaders, in which he ruled against the merger and appointed an emissary to oversee relations between them and put an end to tensions.[287] In the same month, al-Baghdadi released an audio message rejecting al-Zawahiri's ruling and declaring that the merger was going ahead.[288] In October 2013, al-Zawahiri ordered the disbanding of ISIS, putting Al-Nusra Front in charge of jihadist efforts in Syria.[289] Al-Baghdadi, however, contested al-Zawahiri's ruling on the basis of Islamic jurisprudence,[288] and the group continued to operate in Syria. In February 2014, after an eight-month power struggle, al-Qaeda disavowed any relations with ISIS.[84]

According to journalist Sarah Birke, there are "significant differences" between Al-Nusra Front and ISIS. While Al-Nusra actively calls for the overthrow of the Assad government, ISIS "tends to be more focused on establishing its own rule on conquered territory". ISIS is "far more ruthless" in building an Islamic state, "carrying out sectarian attacks and imposing sharia law immediately", she said. While Al-Nusra has a "large contingent of foreign fighters", it is seen as a home-grown group by many Syrians; by contrast, ISIS fighters have been described as "foreign 'occupiers'" by many Syrian refugees.[290] It has a strong presence in mid- and northern Syria, where it has instituted sharia in a number of towns.[120] The group reportedly controlled the four border towns of Atmeh, al-Bab, Azaz and Jarablus, allowing it to control the exit and entrance from Syria into Turkey.[120] Foreign fighters in Syria include Russian-speaking jihadists who were part of Jaish al-Muhajireen wal-Ansar (JMA).[291] In November 2013, the JMA's ethnic Chechen leader Abu Omar al-Shishani swore an oath of allegiance to al-Baghdadi;[292] the group then split between those who followed al-Shishani in joining ISIS and those who continued to operate independently in the JMA under a new leadership.[13]

In May 2014, al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri ordered Al-Nusra Front to stop attacks on its rival ISIS.[25] In June 2014, after continued fighting between the two groups, Al-Nusra's branch in the Syrian town of al-Bukamal pledged allegiance to ISIS.[293][294]

Conflicts with other groups

In Syria, rebels affiliated with the Islamic Front and the Free Syrian Army launched an offensive against ISIS militants in and around Aleppo in January 2014.[295][296]Relations with the Syrian government

The group has special relations with the Syrian government's mukhabarat—intelligence agency—and its bases within Syria are exempt from being targeted by the Syrian air force under the condition that ISIS continues to pump oil to army installations from oilfields that they have captured.[297] The Syrian government did not begin to fight ISIS until June 2014 despite its having a presence in Syria since April 2013, according to Kurdish officials.[298]As Islamic State (2014–present)

On 29 June 2014, ISIS removed "Iraq and the Levant" from its name and began to refer to itself as the Islamic State, declaring the territory under its control a new caliphate and naming Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as its caliph.[5]On the first night of Ramadan, Shaykh Abu Muhammad al-Adnani al-Shami, spokesperson for ISIS, described the establishment of the caliphate as "a dream that lives in the depths of every Muslim believer" and "the abandoned obligation of the era". He said that the group's ruling Shura Council had decided to establish the caliphate formally and that Muslims around the world should now pledge their allegiance to the new caliph.[299][300]

The declaration of a caliphate has been criticized and ridiculed by Muslim scholars and rival Islamists inside and outside the occupied territory.[301][302][303][304][305][306]

Analysts observed that dropping the reference to region reflected a widening of the group's scope, and Laith Alkhouri, a terrorism analyst, thought that after capturing many areas in Syria and Iraq, ISIS felt this was a suitable opportunity to take control of the global jihadist movement.[307] A week before its change of name to the Islamic State, ISIS had captured the Trabil crossing on the Jordan–Iraq border,[308] the only border crossing between the two countries.[309]

ISIS has received some public support in Jordan, albeit limited, partly owing to state repression there,[310] but the group undertook a recruitment drive in Saudi Arabia,[168] where tribes in the north are linked to those in western Iraq and eastern Syria.[311]

In June and July 2014, Jordan and Saudi Arabia moved troops to their borders with Iraq after Iraq lost control of, or withdrew from, strategic crossing points, which were thence under ISIS's command.[51][309] There was speculation that al-Maliki had ordered a withdrawal of troops from the Iraq–Saudi crossings in order "to increase pressure on Saudi Arabia and bring the threat of Isis over-running its borders as well".[311]

After the group captured Kurdish-controlled territory[312] and massacred Yazidis,[313] the US launched a humanitarian mission and aerial bombing campaign against ISIS.[314][315]

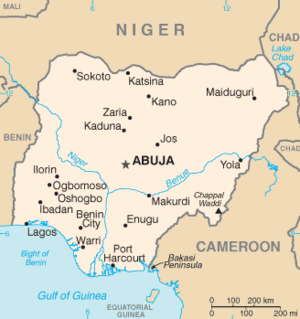

In July 2014, Boko Haram leader Abubakar Shekau declared support for the new Calpihate and Caliph Ibrahim.[20] In August, Abubakar Shekau announced that Boko Haram had captured the Nigerian town of Gwoza in the name of the Caliphate. Shekau announced: "Thanks be to Allah who gave victory to our brothers in Gwoza and made it part of the Islamic caliphate".[316] This announcement appears to be unilateral.

The moderate Free Syrian Army rebels have been backed by the United States with weapons and training.[317][318] However, as of August 2014, according to the high-level commander of the Islamic State, "In the East of Syria, there is no Free Syrian Army any longer. All Free Syrian Army people [there] have joined the Islamic State".[319]

Human rights abuses

ISIS compels people in the areas it controls, under the penalty of death, torture or mutilation, to declare Islamic creed, and live according to its interpretation of Sunni Islam and sharia law.[320][71] It directs violence against Shia Muslims, indigenous Assyrian, Chaldean, Syriac and Armenian Christians, Yazidis, Druze, Shabaks and Mandeans in particular.[127]Treatment of civilians

During the Iraqi conflict in 2014, ISIS released dozens of videos showing its ill treatment of civilians, many of whom had apparently been targeted on the basis of their religion or ethnicity. Navi Pillay, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, warned of war crimes occurring in the Iraqi war zone, and disclosed one UN report of ISIS militants murdering Iraqi Army soldiers and 17 civilians in a single street in Mosul. The United Nations reported that in the 17 days from 5 to 22 June, ISIS killed more than 1,000 Iraqi civilians and injured more than 1,000.[321][322][323] After ISIS released photographs of its fighters shooting scores of young men, the United Nations declared that cold-blooded "executions" said to have been carried out by militants in northern Iraq almost certainly amounted to war crimes.[324]ISIS's advance in Iraq in mid-2014 was accompanied by continuing violence in Syria. On 29 May, a village in Syria was raided by ISIS and at least 15 civilians were killed, including, according to Human Rights Watch, at least six children.[325] A hospital in the area confirmed that it had received 15 bodies on the same day.[326] The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that on 1 June, a 102-year-old man was killed along with his whole family in a village in Hama.[327]

ISIS has recruited to its ranks Iraqi children, who can be seen with masks on their faces and guns in their hands patrolling the streets of Mosul.[328]

Sexual violence allegations

According to one report, ISIS's capture of Iraqi cities in June 2014 was accompanied by an upsurge in crimes against women, including kidnap and rape.[329][330][331] The Guardian reported that ISIS's extremist agenda extended to women's bodies and that women living under their control were being captured and raped.[332] Hannaa Edwar, a leading women’s rights advocate in Baghdad who runs an NGO called al-Amal, said that none of her contacts in Mosul were able to confirm any cases of rape; however, another Baghdad-based women's rights activist, Basma al-Khateeb, said that a culture of violence existed in Iraq against women generally and felt sure that sexual violence against women was happening in Mosul involving not only ISIS but all armed groups.[333] During a meeting with Nouri al-Maliki, British Foreign Minister William Hague said with regard to ISIS: "Anyone glorifying, supporting or joining it should understand that they would be assisting a group responsible for kidnapping, torture, executions, rape and many other hideous crimes".[334] According to Martin Williams in The Citizen, some hard-line Salafists apparently regard extramarital sex with multiple partners as a legitimate form of holy war and it is "difficult to reconcile this with a religion where some adherents insist that women must be covered from head to toe, with only a narrow slit for the eyes".[335] Yezidi girls in Iraq were allegedly raped by ISIS fighters, and subsequently committed suicide, as described in a witness statement recorded by Rudaw.[336]War crimes accusations

The BBC reported the UN's chief investigator as stating: "Fighters from the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (Isis) may be added to a list of war crimes suspects in Syria".[337]Guidelines for civilians

After the self-proclaimed Islamic State captured cities in Iraq, ISIS issued guidelines on how to wear clothes and veils. ISIS warned women in the city of Mosul to wear full-face veils or face severe punishment.[338][339] A cleric told Reuters in Mosul that ISIS gunmen had ordered him to read out the warning in his mosque when worshippers gathered.[338] ISIS also banned naked mannequins and ordered the faces of both male and female mannequins to be covered.[340] ISIS released 16 notes labeled "Contract of the City", a set of rules aimed at civilians in Nineveh. One rule stipulated that women should stay at home and not go outside unless necessary. Another rule said that stealing would be punished by amputation.[137][341]Christians living in areas under ISIS control who wanted to remain in the "caliphate" faced three options, converting to Islam, paying a religious levy—jizya—or death. "We offer them three choices: Islam; the dhimma contract – involving payment of jizya; if they refuse this they will have nothing but the sword", ISIS said.[342] ISIS had already set similar rules for Christians in Ar-Raqqah, Syria, once one of the nation's most liberal cities.[343][344]

Timeline of events

2003–06 events

- The group was founded in 2003 as a reaction to the American-led invasion and occupation of Iraq. Its first leader was the Jordanian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who declared allegiance to Osama bin Laden's al-Qaeda network on 17 October 2004.[345] Foreign fighters from outside Iraq were thought to play a key role in its network.[346] The group became a primary target of the Iraqi government and its foreign supporters, and attacks between these groups resulted in more than 1,000 deaths every year between 2004 and 2010.[347]

- The Islamic State of Iraq made clear its belief that targeting civilians was an acceptable strategy and it has been responsible for thousands of civilian deaths since 2004.[348] In September 2005, al-Zarqawi declared war on Shia Muslims and the group used bombings—especially suicide bombings in public places—massacres and executions to carry out terrorist attacks on Shia-dominated and mixed sectarian neighbourhoods.[349] Suicide attacks by the ISI also killed hundreds of Sunni civilians, which engendered widespread anger among Sunnis.

2007 events

- Between late 2006 and May 2007, the ISI brought the Dora neighborhood of southern Baghdad under its control. Numerous Christian families left, unwilling to pay the jizya tax.[citation needed] US efforts to drive out the ISI presence stalled in late June 2007, despite streets being walled off and the use of biometric identification technology. By November 2007, the ISI had been removed from Dora, and Assyrian churches could be re-opened.[350][not in citation given] In 2007 alone the ISI killed around 2,000 civilians, making that year the most violent in its campaign against the civilian population of Iraq.[348]

- 9 March: The Interior Ministry of Iraq said that Abu Omar al-Baghdadi had been captured in Baghdad,[351] but it was later said that the person in question was not al-Baghdadi.[352]

- 19 April: The organization announced that it had set up a provisional government termed "the first Islamic administration" of post-invasion Iraq. The "emirate" was stated to be headed by Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and his "cabinet" of ten "ministers".[353]

- 3 May: Iraqi sources claimed that Abu Omar al-Baghdadi had been killed a short time earlier. According to the The Long War Journal, no evidence was provided to support this and US sources remained skeptical.[357] The Islamic State of Iraq released a statement later that day which denied his death.[358]

- 12 May: In what was apparently the same incident, it was announced that "Minister of Public Relations" Abu Bakr al-Jabouri had been killed on 12 May 2007 near Taji.[verification needed] The exact circumstances of the incident remain unknown. The initial version of the events at Taji, as given by the Iraqi Interior Ministry, was that there had been a shoot-out between rival Sunni militias. Coalition and Iraqi government operations were apparently being conducted in the same area at about the same time and later sources implied that they were directly involved, with al-Jabouri being killed while resisting arrest. (See Abu Omar al-Baghdadi for details.)

- 12 May: The ISI issued a press release claiming responsibility for an ambush at Al Taqa, Babil on 12 May 2007, in which one Iraqi soldier and four US 10th Mountain Division soldiers were killed. Three soldiers of the US unit were captured and one was found dead in the Euphrates 11 days later. After a 4,000-man hunt by the US and allied forces ended without success, the ISI released a video in which it was claimed that the other two soldiers had been killed and buried, but no direct proof was given. Their bodies were found a year later.[359][360]

- 18 June: The US launched Operation Arrowhead Ripper, as "a large-scale effort to eliminate Al-Qaeda in Iraq terrorists operating in Baquba and its surrounding areas".[361] (See also Diyala province campaign.)

- 25 June: The suicide bombing of a meeting of Al Anbar tribal leaders and officials at Mansour Hotel, Baghdad[362] killed 13 people, including six Sunni sheikhs[363] and other prominent figures. This was proclaimed by the ISI to have been in retaliation for the rape of a Sunni woman by Iraqi police.[364] Security at the hotel, which is 100 meters outside the Green Zone, was provided by a British contractor[365] which had apparently hired guerrilla fighters to provide physical security.[366][not in citation given] There were allegations that an Egyptian Islamist group may have been responsible for the bombing, but this has never been proven.[367]

- In July, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi released an audio tape in which he issued an ultimatum to Iran. He said: "We are giving the Persians, and especially the rulers of Iran, a two-month period to end all kinds of support for the Iraqi Shia government and to stop direct and indirect intervention ... otherwise a severe war is waiting for you." He also warned Arab states against doing business with Iran.[368] Iran supports the Iraqi government which many see as anti-Sunni.[citation needed]

- Resistance to coalition operations in Baqubah turned out to be less than anticipated. In early July, US Army sources suggested that any ISI leadership in the area had largely relocated elsewhere in early June 2007, before the start of Operation Arrowhead Ripper.[369]

2009–12 events

- In the 25 October 2009 Baghdad bombings 155 people were killed and at least 721 were injured,[370] and in the 8 December 2009 Baghdad bombings at least 127 people were killed and 448 were injured.[371] The ISI claimed responsibility for both attacks.

- The ISI claimed responsibility for the 25 January 2010 Baghdad bombings that killed 41 people, and the 4 April 2010 Baghdad bombings that killed 42 people and injured 224. On 17 June 2010, the group claimed responsibility for an attack on the Central Bank of Iraq that killed 18 people and wounded 55.[372] On 19 August 2010, in a statement posted on a website often used by Islamist radicals, the ISI claimed responsibility for the 17 August 2010 Baghdad bombings.[373] It also claimed responsibility for the bombings in October 2010.[verification needed]

- According to the SITE Institute,[374] the ISI claimed responsibility for the 2010 Baghdad church attack that took place during a Sunday Mass on 31 October 2010.[375]

- 8 February 2011: According to the SITE Institute, a statement of support for Egyptian protesters—which appears to have been the first reaction of any group affiliated with al-Qaeda to the protests in Egypt during the 2011 Arab Spring Movement—was issued by the Islamic State of Iraq on jihadist forums. The message addressed to the protesters was that the "market of jihad" had opened in Egypt, that "the doors of martyrdom had opened", and that every able-bodied man must participate. It urged Egyptians to ignore the "ignorant deceiving ways" of secularism, democracy and "rotten pagan nationalism". "Your jihad", it went on, is in support of Islam and the weak and oppressed in Egypt, for "your people" in Gaza and Iraq, and "for every Muslim" who has been "touched by the oppression of the tyrant of Egypt and his masters in Washington and Tel Aviv".[376]

- In a four-month process ending in October 2011, the Syrian government reportedly released imprisoned Islamic radicals and provided them with arms "in order to make itself the least bad choice for the international community."[377]

- 23 July 2012: About 32 attacks occurred across Iraq, killing 116 people and wounding 299. The ISI claimed responsibility for the attacks, which took the form of bombings and shootings.[378]

- In August 2012, two Iraqi refugees who have resided in Kentucky were accused of assisting AQI by sending funds and weapons; one has pleaded guilty.[379]

2013 events

- Starting in April 2013, the group made rapid military gains in controlling large parts of Northern Syria, where the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights described them as "the strongest group".[380]

- 11 May: Two car bombs exploded in the town of Reyhanlı in Hatay Province, Turkey. At least 51 people were killed and 140 injured in the attack.[381] The attack was the deadliest single act of terrorism ever to take place on Turkish soil.[382] Along with the Syrian intelligence service, ISIS was suspected of carrying out the bombing attack.[383]

- By 12 May, nine Turkish citizens, who were alleged to have links with Syria's intelligence service, had been detained.[384] On 21 May 2013, the Turkish authorities charged the prime suspect, according to the state-run Anatolia news agency. Four other suspects were also charged and 12 people had been charged in total. [clarification needed] All suspects were Turkish nationals whom Ankara believed were backed by the Syrian government.[385]

- In July, Free Syrian Army battalion chief Kamal Hamami—better known by his nom de guerre Abu Bassir Al-Jeblawi—was killed by the group's Coastal region emir after his convoy was stopped at an ISIS checkpoint in Latakia's rural northern highlands. Al-Jeblawi was traveling to visit the Al-Izz Bin Abdulsalam Brigade operating in the region when ISIS members refused his passage, resulting in an exchange of fire in which Al-Jeblawi received a fatal gunshot wound.[386]

- Also in July, ISIS organised a mass break-out of its members being held in Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison. British newspaper The Guardian reported that over 500 prisoners escaped, including senior commanders of the group.[387][388] ISIS issued an online statement claiming responsibility for the prison break, describing the operation as involving 12 car bombs, numerous suicide bombers and mortar and rocket fire.[387][388] It was described as the culmination of a one-year campaign called "destroying the walls", which was launched on 21 July 2012 by ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi; the aim was to replenish the group's ranks with comrades released from the prison.[389]

- In early August, ISIS led the final assault in the Siege of Menagh Air Base.[390]

- In September, members of the group kidnapped and killed the Ahrar ash-Sham commander Abu Obeida Al-Binnishi, after he had intervened to protect members of a Malaysian Islamic charity; ISIS had mistaken their Malaysian flag for that of the United States.[391][392]