From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

9K37 Buk

NATO reporting name:

SA-11 Gadfly, SA-17 Grizzly |

|

Buk-M1-2 air defence system in 2010

|

| Type |

Medium range SAM system |

| Place of origin |

Soviet Union |

| Service history |

| In service |

1979–present |

| Used by |

See list of present and former operators |

| Wars |

See combat service |

| Production history |

| Designer |

Almaz-Antey:

- Tikhomirov NIIP (lead designer)

- Lyulev Novator (SA missile designer)

- MNIIRE Altair (naval version designer)

- NIIIP (surveillance radar designer)

- DNPP (missiles)

- UMZ (TELARs)

- MZiK (TELs)[1]

MMZ (GM chassis) |

| Variants |

9K37 "Buk", 9K37M, 9K37M1 "Buk-M1", 9K37M1-2 "Buk-M1-2", 9K37M1-2A, 9K317 "Buk-M2", "Buk-M3"

naval: 3S90 (M-22), 3S90M, 3S90E1, 3S90M1 |

The

Buk missile system (

Russian:

"Бук";

beech,

//) is a family of

self-propelled, medium-range

surface-to-air missile systems developed by the

Soviet Union and its successor state, the

Russian Federation, and designed to fight

cruise missiles,

smart bombs,

fixed- and

rotary-wing aircraft, and

unmanned aerial vehicles.

[2]

The Buk missile system is the successor to the

NIIP/

Vympel 2K12 Kub (

NATO reporting name SA-6 "Gainful").

[3] The first version of

Buk adopted into service carried the

GRAU designation

9K37 and was identified in the west with the NATO reporting name

"Gadfly" as well as the

US Department of Defense designation

SA-11.

Since its initial introduction into service the Buk missile system has

been continually upgraded and refined. With the integration of a new

missile the

Buk-M1-2 and

Buk-M2 systems also received a new NATO reporting name

Grizzly and a new DoD designation

SA-17. The latest incarnation

"Buk-M3" is scheduled for production.

[4]

A naval version of the system, designed by

MNIIRE Altair (currently part of

GSKB Almaz-Antey) for the

Russian Navy, according to

Jane's Missiles & Rockets, received the

GRAU designation

3S90M1 and will be identified with the NATO reporting name

Gollum and a DoD designation

SA-N-7C. The naval system is scheduled for delivery in 2014.

[5]

The apparent shootdown of

Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 on July 17, 2014 is believed to have been caused by the Buk system, giving the weapon international attention.

Development

Development of the 9K37 "Buk" was started on 17 January 1972 at the request of the

Central Committee of the CPSU.

[6]

The development team comprised many of the same institutions that had

been responsible for the development of the previous 2K12 "Kub" (NATO

reporting name "Gainful", SA-6). These included the

Tikhomirov Scientific Research Institute of Instrument Design (NIIP) as the lead designer and the

Novator design bureau who were responsible for the development of the missile armament.

[6]

In addition to the land based missile system a similar system was to be

produced for the naval forces, the result being the 3S90 "Uragan" (

Russian:

"Ураган";

hurricane) which also carries the SA-N-7 and "Gadfly" designations

The Buk missile system was designed to surpass the 2K12 Kub in all parameters and its designers including its chief designer

Ardalion Rastov visited Egypt in 1971 to see Kub in operation.

[8]

Both the Kub and Buk used self-propelled launchers developed by

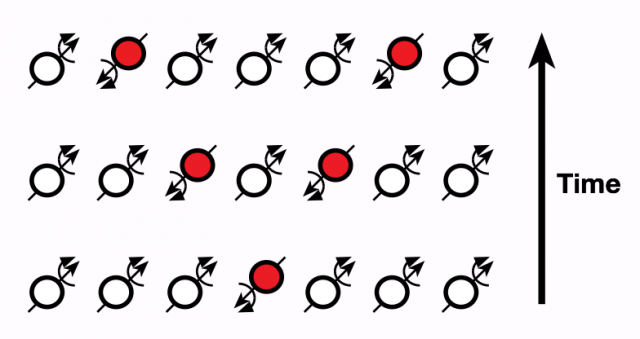

Ardalion Rastov. As a result of this visit the developers came to the

conclusion that each Buk

transporter erector launcher (TEL) should have its own fire control radar rather than being reliant on one central radar for the whole system as in Kub.

[8] The result of this move from TEL to

transporter erector launcher and radar (TELAR) was a system able to engage multiple targets from multiple directions at the same time.

During development in 1974, it was identified that although the Buk

missile system is the successor to the Kub missile system both systems

could share some interoperability, the result of this decision was the

9K37-1 Buk-1 system.

[6]

The advantage of interoperability between Buk TELAR and Kub TEL was an

increase in the number of fire control channels and available missiles

for each system as well as a faster service entry for Buk system

components. The Buk-1 was adopted into service in 1978 following

completion of state trials while the complete Buk missile system was

accepted into service in 1980

[8] after state trials took place between 1977 and 1979.

[6]

The naval variant of the 9K37 "Buk", the 3S-90 "Uragan" was developed by the

Altair design bureau under the direction of chief designer G.N. Volgin.

[9]

The 3S-90 used the same 9M38 missile as the 9K37 though the launcher

and associated guidance radars were exchanged for naval variants. The

9S-90 system was tested between 1974–1976 on the

Kashin-class destroyer Provorny, and accepted into service in 1983 on the Project 956

Sovremenny-class destroyers.

[9]

No sooner than the 9K37, "Buk" had started to enter service than the

next phase of its development was put into operation, in 1979 the

Central Committee of the CPSU authorised the development of a modernised

9K37 which would become the 9K37M1 Buk-M1, adopted into service in

1983.

[6] The modernisation improved the performance of the systems radars, kill probability and resistance to

electronic countermeasures

(ECM). Additionally a non-cooperative threat classification system was

installed, allowing targets to be classified without IFF via analysis of

return radar signals.

[8] The export version of Buk-M1 missile system is known as "Gang" (

Russian:

"Ганг";

Ganges)

[citation needed].

Another modification to the Buk missile system was started in 1992

with work carried out between 1994 and 1997 to produce the 9K37M1-2

Buk-M1-2,

[6] which was accepted into service in 1998.

[10]

This modification introduced a new missile, the 9M317 which offered

improved kinematic performance over the previous 9M38 which could still

be used by the Buk-M1-2. Such sharing of the missile type caused a

transition to a different

GRAU

designations – 9K317 which has been used independently for all later

systems. The previous 9K37 series name was also preserved for the

complex as was the "Buk" name. The new missile as well as a variety of

other improvements allowed the system to intercept ballistic missiles

and surface targets as well as offering improved performance and

engagement envelope against more traditional targets like aircraft and

helicopters.

[6]

The 9K37M1-2 Buk-M1-2 also received a new NATO reporting name

distinguishing it from previous generations of the Buk system, this new

reporting name was the SA-17 Grizzly. The export version of the 9K37M1-2

system is called "Ural" (

Russian:

"Урал")

Shtil-1 SA missile system (graphic)

The introduction of the 9K37M1-2 system for the land forces also

marked the introduction of a new naval variant, the "Ezh" which carries

the NATO reporting name SA-N-7B 'Grizzly' (9M317 missile) and was

exported under the name "Shtil" and carries a NATO reporting name of

SA-N-7C 'Gollum' (9M317E missile), according to

Jane's catalogue.

[7]

The 9K317 incorporates the 9M317 missile to replace the 9M38 used by

the previous system. A further advancement of the system was unveiled as

a concept at

EURONAVAL

2004, a vertical launch variant of the 9M317, the 9M317ME, which is

expected to be exported under the name 3S90E "Shtil-1". Jane's also

reported that in the Russian forces it would have a name of 3S90M

"Smerch" (

Russian:

"Смерч", English translation: '

tornado').

[9][11][12]

The Buk-M1-2 modernisation was based on a previous more advanced developmental system referred to as the 9K317 "Buk-M2".

[6]

This modernisation featured new missiles and a new third generation

phased array fire control radar allowing engagement of up to four

targets while tracking a further 24. A new radar system was also

developed which carried a fire control radar on a 24 m extending boom,

reputedly improving performance against targets flying at low altitude.

[13]

This new generation of Buk missile systems was stalled due to poor

economic conditions after the fall of the Soviet Union. The system was

presented as a static display at the 2007

MAKS Airshow. The export version of the Buk-M2 missile system Buk-M2E is also known as Ural (

Russian:

Урал; English:

Ural)

[citation needed].

In October 2007, Russian General

Nikolai Frolov, commander of the

Ground Forces'

air defense, declared that the Russian Army would receive the brand-new

Buk-M3 to replace the Buk-M1. He stipulated that the M3 would feature

advanced electronic components and enter into service in 2009.

[14] The upgraded Buk-M3 TELAR will have a seven rollers tracked chassis and 6 missiles in launch tubes.

[15]

Description

Inside the TELAR of a Buk-M1 SAM system

A standard Buk battalion consists of a command vehicle,

target acquisition radar (TAR) vehicle, six

transporter erector launcher and radar

(TELAR) vehicles and three transporter erector launcher (TEL) vehicles.

A Buk missile battery consists of two TELAR and one TEL vehicle. The

battery requires no more than 5 minutes to set up before it is ready for

engagement and can be ready for transit again in 5 minutes. The

reaction time of the battery from target tracking to missile launch is

around 22 seconds.

[citation needed]

Inside the TEL of a Buk-M1-2 SAM system

The Buk-M1-2 TELAR uses the

GM-569 chassis designed and produced by JSC

MMZ (

Mytishchi).

[16] TELAR

superstructure

is a turret containing the fire control radar at the front and a

launcher with four ready-to-fire missiles on top. Each TELAR is operated

by a crew of four and is equipped with

CBRN protection. The radar fitted to each TELAR, referred to as the 'Fire Dome' by NATO, is a

monopulse

type radar and can begin tracking at the missile's maximum range

(32 km/20 mi) and can track aircraft flying at between 15 m and 22 km

(50 to 72,000 ft) altitudes. It can guide up to three missiles against a

single target. The 9K37 system supposedly has much better ECCM

characteristics (i.e., is more resistant to

ECM and

jamming) than the

3M9 Kub system that it replaces. While early Buk had a day radar tracking system 9Sh38 (similar to that used on

Kub,

Tor and

Osa missile system),

its current design can be fitted with a combined optical tracking

system with a thermal camera and a laser range-finder for passive

tracking of the target. The 9K37 system can also utilise the same 1S91

Straight Flush 25 kW

G/

H band continuous wave radar as the 3M9 "Kub" system.

The 9S35 radar of the original Buk TELAR uses mechanical scan of

Cassegrain antenna reflector. Buk-M2 TELAR design used a

PESA for tracking and missile guidance.

A Buk-M1-2 SAM system 9S18M1-1 Tube Arm target acquisition radar (TAR) on 2005

MAKS Airshow

The 9K37 utilises the 9S18 "Tube Arm" or 9S18M1 (which carries the NATO reporting name "Snow Drift") (

Russian:

СОЦ 9C18 "Купол";

dome) target acquisition radar in combination with the 9S35 or 9S35M1 "Fire Dome"

H/

I band

tracking and engagement radar which is mounted on each TELAR. The Snow

Drift target acquisition radar has a maximum detection range of 85 km

(53 mi) and can detect an aircraft flying at 100 m (330 ft) from 35 km

(22 mi) away and even lower flying targets at ranges of around 10–20 km

(6–12 mi). Snow Drift is mounted on a chassis similar to that of the

TELAR, as is the command vehicle. The control post which coordinates

communications between the surveillance radar(s) and the launchers is

able to communicate with up to six TELs at once.

Console of the upgraded TELAR of a Buk-M2E

The TEL reload vehicle for the Buk battery resembles the TELAR but instead of a radar, they have a

crane

for the loading of missiles. They are capable of launching missiles

directly but require the cooperation of a Fire Dome-equipped TELAR for

missile guidance. A reload vehicle can transfer its missiles to a TELAR

in around 13 minutes and can reload itself from stores in around 15

minutes.

Also, Buk-M2 featured a new vehicle like TELAR, but with radar on top of a

telescopic lift,

and without missiles, called a target acquisition radar (TAR) 9S36.

This vehicle could be used together with two TELs 9A316 to engage up to

four targets, missile guidance in forested or hilly regions.

Mobile simulator SAM Buk-M2E was shown at MAKS-2013. Self-propelled

fire simulator installation JMA 9A317ET SAM "Buk-M2E" on the basis of

the mobile is designed for training and evaluating combat crew in the

work environment to detect, capture, maintenance and defeat targets.

Computer Information System fully record all actions of the crew to a

"black box" to allow objectively assess the consistency of the actions

and results.

[17]

All vehicles of Buk-M1 (Buk-M1-2) missile system uses an Argon-15A computer as

Zaslon radar

does (the first airborne digital computer designed in 1972 by the

Soviet Research Institute of Computer Engineering (NICEVT, currently

NII Argon) and produced at "

Kishinev plant of 50 Years of USSR".

[18][19]

The vehicles of Buk-M2 (Buk-M2E) missile system use a slightly upgraded

version of Argon-A15K. This processor is also used in such military

systems as

anti-submarine defense Korshun and

Sova, airborne radars for

MiG-31 and

MiG-33, mobile tactical missile systems

Tochka,

Oka and

Volga. Currently, Argons are upgraded into Baget series of processors by NIIP.

Basic missile system specifications

- Target acquisition range (by TAR 9S18M1, 9S18M1-1)

- Range: 140[clarification needed]

- Altitude: 60 meters – 25 kilometers (197 feet – 15.5 miles)

- Firing groups in one division: up to 6 (with one command post)

- Firing groups operating in a sector

- 90° in azimuth, 0–7° and 7–14° in elevation

- 45° in azimuth, 14–52° in elevation

- Radar mast lifting height (for TAR 9S36): 21 meters

- Reloading of 4 missiles by TEL from itself: around 15 minutes

- Combat readiness time: no more than 5 minutes

- Kill probability (by one missile): 90–95%

- Target engagement zone

- Aircraft

- Altitude: 15 meters – 25 kilometers (50 feet – 15.5 miles)

- Range: 3–42 kilometres (2–26 miles)

- Tactical ballistic missiles

- Altitude: 2.0–16 kilometres (1.2–9.9 miles)

- Range: 3–20 kilometres (1.9–12.4 miles)

- Sea targets: up to 25 kilometres (16 miles)

- Land targets: up to 15 kilometres (9.3 miles)

Integration with higher level command posts

The basic

command post

of the Buk missile system is 9С510 (9K317 Buk-M2), 9S470M1-2 (9K37M1-2

Buk-M1-2) and 9S470 (Buk-M1) vehicles organizing the Buk system into a

battery. It is capable of linking with various higher level command

posts (HLCPs).

As an option it could be combined into the brigade with the use of HLCP, but not mixing into a unified battery.

The Buk missile system may be controlled by an upper level command post system

9S52 Polyana-D4 integrating it with S-300V/

S-300VM into an air defence brigade.

[20][21] Also it may be controlled by an upper level command post system 73N6ME «Baikal-1ME»

[22] together with 1-4 units of

PPRU-M1 (PPRU-M1-2), integrating it with SA-19 "Grison" (

9K22 Tunguska) (6-24 units total) into an air defence brigade.

[23] With the use of the mobile command center

Ranzhir or

Ranzhir-M (

GRAU designations 9S737, 9S737М) the Buk missile system allows to create mixed groups of air defense forces, including

Tor,

Tungushka,

Strela-10, and

Igla.

[24] "Senezh"

[25] is another optional command post for a free mixing of any systems.

3S90 "Uragan"

The 3S90 "Uragan" (

Russian:

Ураган;

hurricane)

is the naval variant of the 9K37 "Buk" and has the NATO reporting name

"Gadfly" and US DoD designation SA-N-7, it also carries the designation

M-22. The export version of this system is known as "Shtil" (

Russian:

Штиль;

still).

The 9М38 missiles from the 9K37 "Buk" are also used on the 3S90

"Uragan". The launch system is different with missiles being loaded

vertically onto a single arm trainable launcher, this launcher is

replenished from an under-deck magazine with a 24 round capacity,

loading takes 12 seconds to accomplish.

[9] The Uragan utilises the MR-750 Top Steer

D/

E band

as a target acquisition radar (naval analogue of the 9S18 or 9S18M1)

which has a maximum detection range of 300 km (190 mi) depending on the

variant. The radar performing the role of the 9S35 the 3R90 Front Dome

H/

I band tracking and engagement radar with a maximum range of 30 km (19 mi).

3S90 "Ezh"

The modernised version of the 3S90 the 9K37M1-2 (or 9K317E) "Ezh"

which carries the NATO reporting name "Grizzly" or SA-N-12 and the

export designation "Shtil" was developed which uses the new 9M317

missile. This variant was supposed to be installed on Soviet

Ulyanovsk-class nuclear aircraft carriers, and has been retrofitted to the

Sovremenny-class destroyers.

[citation needed].

In 1997, India signed a contract for the three Project 1135.6

frigates with "Shtil". Later, when the decision was made to modernize it

with a new package of hardware & missiles, the name changed to

"Shtil-1".

3S90M "Shtil-1"

In 2004, the first demonstration module of the new 9M317ME missile was presented by

Dolgoprudniy Scientific and Production Plant for the upgraded 3S90M "Shtil-1" naval missile system (jointly with

'Altair'). Designed primary for the export purpose, its latest variant used a

vertical launch

missile which is fired from under-deck silos clustered into groups of

twelve, twenty-four or thirty-six. The first Shtil-1 systems were

installed into ships exported to India and China.

[26][27] Old systems Uragan, Ezh and Shtil could be upgraded to Shtil-1 by replacing the launcher module inside the ship.

Missiles

| 9М38 |

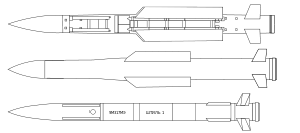

Comparison of 9M38M1, 9M317 and 9M317ME surface-to-air missiles of the Buk missile system

|

| Type |

Surface-to-air missile |

| Place of origin |

Soviet Union |

| Production history |

| Variants |

9М38, 9М38M1, 9M317 |

| Specifications (9М38, 9M317) |

| Weight |

690 kg, (1521 Lbs) 715 kg,(1576 Lbs) |

| Length |

5.55 m (18'-3") |

| Diameter |

0.4 m (15 3/4") (wingspan 0.86 m)(2'-10") |

| Warhead |

Frag-HE |

| Warhead weight |

70 kg,(154.3 Lbs) |

|

Detonation

mechanism

|

Radar proximity fuse |

|

| Propellant |

Solid propellant rocket |

|

Operational

range

|

30 kilometres (19 mi) |

| Flight altitude |

14,000 metres (46,000 ft) |

| Speed |

Mach 3 |

|

Guidance

system

|

Semi-active radar homing |

|

Launch

platform

|

See structure |

9М38 and 9М38M1 missile

The 9M38 uses a single-stage X-winged design without any detachable parts; its exterior design is similar to the American

Tartar and

Standard surface-to-air missile series, which led to the half-serious nickname of

Standardski.

[28]

The design had to conform to strict naval dimension limitations,

allowing the missile to be adapted for the M-22 SAM system in the

Soviet Navy.

Each missile is 5.55 m (18.2 ft) long, weighs 690 kg (1,520 lb) and

carries a relatively large 70 kg (150 lb) warhead which is triggered by a

radar

proximity fuze. In the forward compartment of the missile, a semi-active homing radar head (9E50,

Russian:

9Э50, 9Э50М1), autopilot equipment, power source and warhead are located. The homing method chosen was

proportional navigation.

Some elements of the missile were compatible with the Kub's 3M9; for

example, its forward compartment diameter (33 cm), which was less than

the rear compartment diameter.

9M317 surface-to-air missile on the Buk-M2 quadruple launcher.

The 9M38 surface-to-air missile utilizes a two-mode

solid fuel rocket engine with total burn time of about 15 seconds; the

combustion chamber

is reinforced by metal. For the purpose of reducing the centering

dispersion while in flight, the combustion chamber is located close to

the center of the missile and includes a longer gas pipe. A direct-flow

engine was not used because of its instability at large

angle of attack and by a larger air resistance on a passive trajectory section as well as by some technical difficulties.

[citation needed] Those difficulties had already wrecked plans to create the missile for Kub.

[citation needed]

9M38 is capable of readiness without inspection for at least 10 years

of service. The missile is delivered to the army in the 9Ya266 (9Я266)

transport container.

It has been suggested that the

Novator KS-172 AAM-L, an extremely long range

air-to-air missile and possible

anti-satellite weapon, is a derivative of the 9M38.

[citation needed]

9M317 missile

The 9M317 missile was developed as a common missile for the Russian Ground Force's

Soviet Air Defence Forces (PVO) (using

Buk-M1-2) as well as for ship-based PVO of the

Russian Navy (

Ezh). Its exterior design bears a resemblance to the

Vympel R-37 air-to-air missile.

The unified multi-functional 9M317 (export designation 9M317E) can be used to engage aerodynamic, ballistic, above-water and

radio contrast targets from both land and sea. Examples of targets include tactical

ballistic missiles, strategic

cruise missiles,

anti-ship missiles, tactical, strategic and army aircraft and helicopters. It was designed by OJSC

Dolgoprudny Scientific Production Plant

(DNPP). The maximum engagable target speed was 1200 m/s and it can

tolerate an acceleration overload of 24G. It was first used with

Buk-M1-2 system of the land forces and the Shtil-1 system of the naval

forces.

In comparison with 9M38M1, the 9M317 has a larger defeat area, which

is up to 45 km of range and 25 km of altitude and of lateral parameter,

and a larger target classification. Externally the 9M317 differs from

the 9M38M1 by a smaller wing chord. It uses the inertial correction

control system with semi-active radar homing, utilising the

proportional navigation (PN) targeting method.

The semi-active missile homing radar head (used in 9E420,

Russian:

9Э420) as well as 9E50M1 for the 9M38M1 missile (9E50 for 9M38) and 1SB4 for Kub missile (

Russian:

1СБ4) was designed by

MNII Agate (

Zhukovskiy) and manufactured by

MMZ at

Ioshkar-Ola.

9M317M and 9M317A missile development projects

Currently, several modernized versions are in development, including the 9M317M / 9M317ME, and

active radar homing (ARH) missile 9M317A / 9M317MAE.

The lead developer,

NIIP, reported the testing of the 9M317A missile within Buk-M1-2A

"OKR Vskhod" (

Sprout in English) in 2005.

[29] Range is reported as being up to 50 km (31 mi), maximum altitude around 25 km (82,000 ft) and maximum target speed around

Mach 4. The weight of the missile has increased slightly to 720 kg (1587 lb).

The missile's

Vskhod development program for the Buk-M1-2A was

completed in 2011. This missile could increase the survival capability

and firing performance of the Buk-M1-2A using its ability to hit targets

over the skyline.

[30]

In 2011,

Dolgoprudny NPP completed preliminary trials of the new autonomous target missile system

OKR Pensne (

pince-nez in English) developed from earlier missiles.

[30]

9M317ME missile

The weight of the missile is 581 kg, including the 62 kg

blast fragmentation

warhead initiated by a dual-mode radar proximity fuze. Dimensions of

the hull are 5.18 m length; 0.36 m maximum diameter. Range is 2.5–32 km

in a 3S90M "Shtil-1" naval missile system. Altitude of targets from 15 m

up to 15 km (and from 10 m to 10 km against other missiles). 9M317ME

missiles can be fired at 2-second intervals, while its reaction

(readiness) time is up to 10 s.

The missile was designed to be single-staged, semi-active radio command radar homing with inertial guidance.

[26]

The tail surfaces have a span of 0.82 m when deployed after the

missile leaves the launch container by a spring mechanism. Four

gas-control vanes operating in the motor efflux turn the missile towards

the required direction of flight. After the turnover manoeuvre, they

are no longer used and subsequent flight controlled via moving tail

surfaces. A dual-mode solid-propellant rocket motor provides the missile

with a maximum speed of Mach 4.5.

[31]

Original design tree

- 9K37-1 'Buk-1' – First Buk missile system variant accepted into

service, incorporating a 9A38 TELAR within a 2K12M3 Kub-M3 battery.

- 9K37 'Buk'- The completed Buk missile system with all new system components, back-compatible with 2K12 Kub.

- 9K37M1 'Buk-M1' – An improved variant of the original 9K37 which entered into service with the then Soviet armed forces.

- 9K37M1-2 'Buk-M1-2' ('Gang' for export markets) – An improved

variant of the 9K37M1 'Buk-M1' which entered into service with the

Russian armed forces.

- 9K317 'Ural' (9K37M2) – initial design of Buk-M2 which entered into service with the Russian armed forces

- 9K317E 'Buk-M2E' - revised design for export markets[40]

Backside of the 9A317 TELAR of Buk-M2E (export version) at 2007 MAKS Airshow

9A317 TELAR of Buk-M2E (export version) at 2007 MAKS Airshow

- 9K37M1-2A 'Buk-M1-2A' - redesign of Buk-M1-2 for the use of 9M317A missile

- 'Buk-M2EK'[41] – A wheeled variant of Buk-M2 on MZKT-6922 chassis exported to Venezuela and Syria.

- 9K317M 'Buk-M3' (9K37M3) – In Russian some active work is being

conducted, aimed at the new perspective complex of Buk-M3. A

zenith-rocket division of it will have 36 target channels in total. It

will feature advanced electronic components.

Naval version design tree

- 3S90/M-22 'Uragan' (SA-N-7 "Gadfly") – Naval version of the 9K37 Buk missile system with 9M38/9M38M1 missile.

- 3S90 "Ezh" (SA-N-7B/SA-N-12 'Grizzly') – Naval version of the 9K37M1-2 with 9M317 missile.

- 3S90 "Shtil" (SA-N-7C 'Gollum') – Naval export version of the 9K37M1-2 with 9M317E missile.

- 3S90E "Shtil-1" (SA-N-12 'Grizzly') – Naval export version with 9M317ME missile.

- 3S90M "Smerch" (SA-N-12 'Grizzly') – Possible naval version with 9M317M missile.

Copies

Belarus – In May on the MILEX-2005 exposition in Minsk, Belarus presented their own modification of 9K37 Buk called Buk-MB.[42]

On 26 June 2013 an exported version of Buk-MB was displayed on a

military parade in Baku. It included the new 80K6M Ukrainian-build radar

on an MZKT chassis (instead the old 9S18M1) and the new Russian-build

missile 9M317 (as in Buk-M2).[43]

Belarus – In May on the MILEX-2005 exposition in Minsk, Belarus presented their own modification of 9K37 Buk called Buk-MB.[42]

On 26 June 2013 an exported version of Buk-MB was displayed on a

military parade in Baku. It included the new 80K6M Ukrainian-build radar

on an MZKT chassis (instead the old 9S18M1) and the new Russian-build

missile 9M317 (as in Buk-M2).[43] People's

Republic of China – HQ-16 (Hongqi-16) - People's Republic of China

project based on the naval 9K37M1-2 system 'Shtil' (SA-N-12).[44]

Other sources also rumored the project involved some Buk technology. It

is able to engage high altitude and very low flying targets.[45]

The most visual distinction between SA-17 and HQ-16 is that the latter

is truck-based and vertically launched instead of track based SA-17, its

total number of missiles increased to six from the original four in

SA-17 system.

People's

Republic of China – HQ-16 (Hongqi-16) - People's Republic of China

project based on the naval 9K37M1-2 system 'Shtil' (SA-N-12).[44]

Other sources also rumored the project involved some Buk technology. It

is able to engage high altitude and very low flying targets.[45]

The most visual distinction between SA-17 and HQ-16 is that the latter

is truck-based and vertically launched instead of track based SA-17, its

total number of missiles increased to six from the original four in

SA-17 system.

People's Republic of China – HQ-16A – Improvement of the HQ-16, with redesigned control surfaces incorporating leading edge, thus has better performance at higher angle of attack than HQ-16.

People's Republic of China – HQ-16A – Improvement of the HQ-16, with redesigned control surfaces incorporating leading edge, thus has better performance at higher angle of attack than HQ-16. People's Republic of China – HQ-16B – Further improvement of HQ-16A[46][47]

People's Republic of China – HQ-16B – Further improvement of HQ-16A[46][47] People's Republic of China – LY80 – Export version of HQ-16A,[48][49] incorporating cold vertical launch method

People's Republic of China – LY80 – Export version of HQ-16A,[48][49] incorporating cold vertical launch method

Iran – Raad

Medium Ranged Surface-to-Air Missile System using Ta'er 2 missiles. It

has very similar layout to wheeled Buk-M2EK 9M317. It was shown during

2012 military parade.[50]

Iran – Raad

Medium Ranged Surface-to-Air Missile System using Ta'er 2 missiles. It

has very similar layout to wheeled Buk-M2EK 9M317. It was shown during

2012 military parade.[50]

Operational service

TELAR of

Finnish 9K37M1 Buk-M1 (SA-11 Gadfly) from the left side (missiles locked in a transport position)

In 1996 Finland started operating the eighteen missile systems that they received from Russia as debt payment.

[76] According to

Suomen Kuvalehti,

Finland is planning to accelerate the replacement of the missile system

due to concerns about its susceptibility to electronic warfare.

[77][78]

Combat service

Abkhaz authorities claimed that Buk air defense system was used to shoot down four Georgian drones at the beginning of May 2008.

[79]

Analysts concluded that Georgian Buk missile systems were responsible for downing four Russian aircraft—three

Sukhoi Su-25 close air support aircraft and a

Tupolev Tu-22M strategic bomber—in the

2008 South Ossetia war.

[80]

U.S. officials have said Georgia's SA-11 Buk-1M was certainly the cause

of the Tu-22M's loss and contributed to the losses of the three Su-25s.

[81]

According to some analysts, the loss of four aircraft is surprising and

a heavy toll for Russia given the small size of Georgia's military.

[82][83] Some have also pointed out, that Russian

electronic counter-measures systems were apparently unable to jam and suppress enemy SAMs in the conflict

[84] and that Russia was, surprisingly, unable to come up with effective countermeasures against missile systems it had designed.

[80]

Georgia bought these missile systems from Ukraine which had an inquiry to identify if the purchase was illegal.

[85]

On 29 January 2013, the

Israeli Air Force launched an airstrike on a convoy in Syria believed to have SA-17 BUK-M2E missiles bound for

Hezbollah in Lebanon. The Syrian government denied that the shipment of weapons was taking place.

[86]

The system is suspected of having been involved in the downing of

Malaysia Airlines Flight 17 (a

Boeing 777-200ER) on 17 July 2014 with 298 fatalities in eastern Ukraine's Donetsk Oblast.

[87]

Videos posted by Russian-backed separatist forces after the crash

claimed to have used the system to bring down what they claimed was an

An-26 in the area of the crash, and allegedly showed images of the burning wreckage of MH17 in the distance as evidence.

[