Search This Blog

Wikipedia

Search results

Tuesday, October 28, 2014

Monday, October 27, 2014

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Monday, October 20, 2014

Sunday, October 19, 2014

Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

Philology[show]

|

Peoples and societies[show]

|

Archaeology[show]

|

Religion and mythology[show]

|

Beginning in the 1970s, the mainstream consensus among Indo-Europeanists favors the "Kurgan hypothesis", placing the Indo-European homeland in the Pontic steppe of the Chalcolithic period (4th to 5th millennia BCE). The Pontic steppe is a large area of grasslands in far Eastern Europe, located north of the Black Sea, Caucasus Mountains and Caspian Sea and including parts of eastern Ukraine, southern Russia and northwest Kazakhstan. This is the time and place of the earliest domestication of the horse, which according to this hypothesis was the work of early Indo-Europeans, allowing them to expand outwards and assimilate or conquer many other cultures.

The primary competitor to the Kurgan hypothesis advanced by Marija Gimbutas is the Anatolian hypothesis advanced by Colin Renfrew. Renfrew’s theory has been popular among archeologists, but linguists have by and large preferred the pastoralist model.[1]

All hypotheses assume a significant period (at least 1500–2000 years) between the time of the Proto-Indo-European language and the earliest attested texts, at Kültepe, ca 19th century BCE.

Contents

Hypotheses

There are three main competing basic models (with variations) that have academic credibility (Mallory (1997:106)):- the Kurgan hypothesis (Pontic-Caspian area): Chalcolithic (5th to 4th millennia BCE)

- the Anatolian hypothesis (Anatolia in Asia Minor): Early Neolithic (7th to 5th millennia BCE)

- the Balkan hypothesis, excluding the Anatolian languages (a variant of the Anatolian hypothesis): Neolithic (5th millennium BCE)

A number of fringe hypotheses also exist, e.g.:

- the Armenian hypothesis (proposed in the context of Glottalic theory), with a homeland in Armenia in the 4th millennium BCE (excluding the Anatolian branch);

- a 6th millennium BCE or later origin in Northern Europe, according to Lothar Kilian's and, especially, Marek Zvelebil's[4] models of a broader homeland;

- Koenraad Elst's Out of India theory with a homeland in India in the 6th millennium BCE;[5]

- The Paleolithic Continuity Theory, with an origin before the 10th millennium BCE

- Nikolai Trubetzkoy's theory of Sprachbund origin of Indo-European traits.

Archaeology

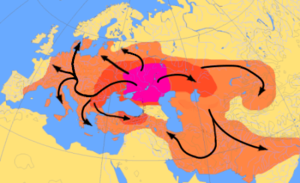

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BCE according to the Kurgan hypothesis. The magenta area corresponds to the assumed Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture).

The red area corresponds to the area which may have been settled by

Indo-European-speaking peoples up to ca. 2500 BCE; the orange area to

1000 BCE.

Indo-European isoglosses, including the centum and satem languages (blue and red, respectively), augment, PIE *-tt- > -ss-, *-tt- > -st-, and m-endings.

Kurgan hypothesis

In the 1970s, a mainstream consensus had emerged among Indo-Europeanists in favour of the "Kurgan hypothesis" placing the Indo-European homeland in the Pontic steppe of the Chalcolithic period. This was not least due to the influence of the Journal of Indo-European Studies, edited by J. P. Mallory, that focused on the ideas of Marija Gimbutas, and offered some improvements. She had created a modern variation on the traditional invasion theory (the Kurgan hypothesis, after the kurgans, burial mounds, of the Eurasian steppes) in which the Indo-Europeans were a nomadic tribe in Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia and expanded on horseback in several waves during the 3rd millennium BCE. Their expansion coincided with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see battle-axe people), they subjugated the peaceful European Neolithic farmers of Gimbutas's Old Europe. As Gimbutas's beliefs evolved, she put increasing emphasis on the patriarchal, patrilinear nature of the invading culture, sharply contrasting it with the supposedly egalitarian, if not matrilinear culture of the invaded, to the point of formulating essentially a feminist archaeology.Her interpretation of Indo-European culture found genetic support in remains from the Neolithic culture of Scandinavia, where DNA from bone remains in Neolithic graves indicated that the megalith culture was either matrilocal or matrilineal, as the people buried in the same grave were related through the women. Likewise, there is a tradition of remaining matrilineal traditions among the Picts. J.P. Mallory, dating the migrations earlier, to around 4000 BCE, and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, essentially modified Gimbutas' theory.

The Gimbutas-Mallory Kurgan hypothesis seeks to explain the Indo-European language expansion by a succession of migrations from the Pontic-Caspian steppe, or, more specifically and according to the revised version, to the area encompassed by the Sredny Stog culture (ca. 4500 BCE). This hypothesis is compatible with the argument that the PIE homeland must have been larger,[6] because the "Neolithic creolisation hypothesis" allows the Pontic-Caspian region to have been part of PIE territory.

A variant of the Kurgan hypothesis is the "Sogdiana hypothesis" of Johanna Nichols, placing the homeland in the 4th or 5th millennium BCE to the east of the Caspian Sea, in the area of ancient Bactria-Sogdiana.[7][8]

Anatolian hypothesis

The main competitor to the Kurgan hypothesis is the Anatolian hypothesis advanced by Colin Renfrew. It states that the Indo-European languages began to spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BCE with the Neolithic advance of farming (wave of advance). The expansion of agriculture from the Middle East would have diffused three language families: Indo-European toward Europe, Dravidian toward Pakistan and India, and Afro Asiatic toward Arabia and North Africa. Essentially the same hypothesis was suggested, based on genetic haplogroup distribution, by Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza.[9]The main objections to this theory are:

- It requires an unrealistically early date. The Proto-Indo-European lexicon includes words for a range of inventions and practices related to the Secondary Products Revolution, which post-dates the early spread of farming. On lexico-cultural dating, Proto-Indo-European cannot be earlier than 4000 BC.[10]

- The idea that farming was spread from Anatolia in a single wave has been revised. Instead it appears to have spread in several waves by several routes, primarily from the Levant.[11] The trail of plant domesticates indicates an initial foray from the Levant by sea.[12] The overland route via Anatolia seems to have been most significant in spreading farming into south-east Europe.[13]

- Non-Indo-European languages appear to be associated with the spread of farming from the Near East into North Africa and the Caucasus.

- Anatolia was inhabited by non-Indo-European speakers, including the Hattians, who appear to pre-date the arrival there of the Indo-European speakers of the Anatolian branch, since the latter borrowed words from the former.

Genetics

Further information: Kurgan hypothesis#Genetics

The accumulation of Archaeogenetic evidence which uses genetic analysis to trace migration patterns since the 1990s has also added new elements to the puzzle. Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza argue that Renfrew and Gimbutas reinforce rather than contradict each other. Cavalli-Sforza (2000)

states that "It is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the

Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle

Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey." Piazza &

Cavalli-Sforza (2006) state that:if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavorable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.Wells (2002) states that "there is nothing to contradict this model, although the genetic patterns do not provide clear support either," and instead argues that the evidence is much stronger for Gimbutas' model:

while we see substantial genetic and archaeological evidence for an Indo-European migration originating in the southern Russian steppes, there is little evidence for a similarly massive Indo-European migration from the Middle East to Europe. One possibility is that, as a much earlier migration (8,000 years old, as opposed to 4,000), the genetic signals carried by Indo-European-speaking farmers may simply have dispersed over the years. There is clearly some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East, as Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues showed, but the signal is not strong enough for us to trace the distribution of Neolithic languages throughout the entirety of Indo-European-speaking Europe.Haplogroup R1a1 is associated with the Kurgan culture. R1a1 shows a strong correlation with Indo-European languages of western Asia and eastern Europe, being most prevalent in Poland, Russia, and Ukraine and also observed in Pakistan, India and central Asia. The connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages was first noted by T. Zerjal and colleagues in 1999.[17] Ornella Semino and colleagues proposed a postglacial spread of the R1a1 gene during the Late Glacial Maximum, subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.[18] Spencer Wells suggests that the distribution and age of R1a1 points to an ancient migration corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion from the Eurasian steppe.[19]

Ancient DNA has confirmed the connection with kurgan burials directly. Out of ten human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, nine possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C haplogroup (xC3). Mitochrondrial DNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (2 individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b. 90% of the Bronze Age period mtDNA haplogroups were of west Eurasian origin and the study determined that at least 60% of the individuals overall (out of the 26 Bronze and Iron Age human remains' samples of the study that could be tested) had light hair and blue or green eyes. Significantly, R1a also appeared in later kurgan steppe burials through a series of related cultures up to the Scythians, known to speak an Indo-European language.[20]

Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

\

| Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (c. 4800 to 3000 BC) |

|---|

Characteristic example of Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery

|

| Topics |

| Related articles |

| Chalcolithic Eneolithic, Aeneolithic Copper Age |

|---|

| ↑ Stone Age ↑ Neolithic |

| Metallurgy, Wheel, Domestication of the horse, |

| ↓ Bronze Age |

It extends from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of some 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of some 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kiev in the northeast to Brasov in the southwest).[3][4]

The majority of Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys.[5] During the Middle Trypillia phase (ca. 4000 to 3500 BC), populations belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as 1,600 structures.[6]

One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a roughly 60 to 80 year lifetime.[7] The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location, the Poduri site (Romania), revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.[7]

Contents

Nomenclature

The culture was initially named after the village of Cucuteni in Iaşi County, Romania. In 1884 Teodor T. Burada, after having seen ceramic fragments in the gravel used to maintain the road from Târgu Frumos to Iași, investigated the quarry in Cucuteni from where the material was mined, where he found fragments of pottery and terracotta figurines. Burada and other scholars from Iaşi, including the poet Nicolae Beldiceanu and archeologists Grigore Butureanu, Dimitrie C. Butculescu and George Diamandy, subsequently began the first excavations at Cucuteni in the spring of 1885.[8] Their findings were published in 1885[9] and 1889,[10] and presented in two international conferences in 1889, both in Paris: at the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology by Butureanu[8] and at a meeting of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris by Diamandi.[11]The first Ukrainian sites ascribed to the culture were discovered by Vicenty Khvoika. The year of his discoveries has been variously claimed as 1893,[12] 1896[13] and 1887.[14] In any case Khvoika presented his findings at the 11th Congress of Archaeologists in 1897, which is considered the official date of the discovery of the Trypillian culture in Ukraine.[12][14] In the same year similar artifacts were excavated in the village of Trypillia (Ukrainian: Трипiлля, Russian: Трипольe) in Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. As a result, this culture became identified in Soviet, Russian, and Ukrainian publications as the 'Tripolie' (or 'Tripolye'), 'Tripolian' or 'Trypillian' culture.

Today the finds from both countries, as well as those from Moldova, are recognized as belonging to the same cultural complex. This is generally known as the Cucuteni culture in Romania and the Trypillian culture (variously romanized) in Ukraine. In English, 'Cucuteni-Tripolye culture' is most commonly used to refer to the whole culture,[15] with the Ukrainian-derived term 'Cucuteni-Tripillian culture' gaining currency following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Geography

The culture thus extended northeast from the Danube River Basin around the Iron Gates gorge to the Black Sea and Dnieper River. It encompassed the central Carpathian Mountains as well as the plains, steppe and forest steppe on either side of the range. Its historical core lay around the middle to upper Dniester River (the Podolian Upland).[4] During the Atlantic and Subboreal climatic periods in which the culture flourished, Europe was at its warmest and moistest since the end of the last Ice Age, creating favorable conditions for agriculture in this region.

As of 2003, about 3,000 cultural sites have been identified,[7] ranging from small villages to "vast settlements consisting of hundreds of dwellings surrounded by multiple ditches".[16]

Chronology

Periodization

Traditionally separate schemes of periodization have been used for the Ukrainian Trypillian and Romanian Cucuteni variants of the culture. The Cucuteni scheme, proposed by the German archeologist Hubert Schmidt in 1932,[17] distinguished three cultures: Precucuteni, Cucuteni and Horodiştea-Folteşti; which were further divided into phases (Precucuteni I-III and Cucuteni A and B).[18] The Ukrainian scheme was first developed by Tatiana Sergeyevna Passek in 1949[19] and divided the Trypillia culture into three main phases (A, B and C) with further sub-phases (BI-II and CI-II).[18] Initially based on informal ceramic seriation, both schemes have been extended and revised since first proposed, incorporating new data and formalised mathematical techniques for artifact seriation.[20](p103)The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is commonly divided into an Early, Middle, Late period, with varying smaller sub-divisions marked by changes in settlement and material culture. A key point of contention lies in how these phases correspond to radiocarbon data. The following chart[18] represents this most current interpretation:

| • Early (Precucuteni I-III to Cucuteni A-B, Trypillia A to Trypillia BI-II): | 4800 to 4000 BC |

| • Middle (Cucuteni B, Trypillia BII to CI-II): | 4000 to 3500 BC |

| • Late (Horodiştea-Folteşti, Trypillia CII): | 3500 to 3000 BC |

Early period (4800-4000 BC)

The roots of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture can be found in the Starčevo-Körös-Criș and Vinča cultures of the 6th to 5th millennia,[7] with additional influence from the Bug-Dniester culture (6500-5000 BC).[21] During the early period of its existence (in the 5th millennium BC), the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was also influenced by the Linear Pottery culture from the north, and by the Boian-Giulesti culture from the south.[7] Through colonization and acculturation from these other cultures, the formative Precucuteni/Trypillia A culture was established. Over the course of the fifth millennium, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture expanded from its 'homeland' in the Prut-Siret region along the eastern foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into the basins and plains of the Dnieper and Southern Bug rivers of central Ukraine.[22] Settlements also developed in the southeastern stretches of the Carpathian Mountains, with the materials known locally as the Ariuşd culture (see also: Prehistory of Transylvania). Most of the settlements were located close to rivers, with fewer settlements located on the plateaus. Most early dwellings took the form of pit houses, though they were accompanied by an ever-increasing incidence of above-ground clay houses.[22] The floors and hearths of these structures were made of clay, and the walls of clay-plastered wood or reeds. Roofing was made of thatched straw or reeds.The inhabitants were involved with animal husbandry, agriculture, fishing and gathering. Wheat, rye and peas were grown. Tools included plows made of antlers, stone, bone and sharpened sticks. The harvest was collected with scythes made of flint-inlaid blades. The grain was milled into flour by stone wheels. Women were involved in pottery, textile- and garment-making, and played a leading role in community life. Men hunted, herded the livestock, made tools from flint, bone and stone. Of their livestock, cattle were the most important, with swine, sheep and goats playing lesser roles. The question of whether or not the horse was domesticated during this time of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is disputed among historians; horse remains have been found in some of their settlements, but it is unclear whether these remains were from wild horses or domesticated ones.

Clay statues of females and amulets have been found dating to this period. Copper items, primarily bracelets, rings and hooks, are occasionally found as well. A hoard of a large number of copper items (a Treasure - see image) was discovered in the village of Cărbuna, Moldova, consisting primarily of items of jewelry, which were dated back to the beginning of the 5th millennium BC. Some historians have used this evidence to support the theory that a social stratification was present in early Cucuteni culture, but this is disputed by others.[7]

Pottery remains from this early period are very rarely discovered; the remains that have been found indicate that the ceramics were used after being fired in a kiln. The outer color of the pottery is a smoky gray, with raised and sunken relief decorations. Toward the end of this early Cucuteni-Trypillian period, the pottery begins to be painted before firing. The white-painting technique found on some of the pottery from this period was imported from the earlier and contemporary (5th millennium) Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture. Historians point to this transition to kiln-fired, white-painted pottery as the turning point for when the Precucuteni culture ended and Cucuteni Phase (or Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture) began.[7]

Cucuteni and the neighbouring Gumelniţa-Karanovo cultures seem to be largely contemporary,

"Cucuteni A phase seems to be very long (4600-4050) and covers the entire evolution of Gumelniţa culture A1, A2, B2 phases (maybe 4650-4050)."[23]

Middle period (4000-3500 BC)

In the middle era the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture spread over a wide area from Eastern Transylvania in the west to the Dnieper River in the east. During this period, the population immigrated into and settled along the banks of the upper and middle regions of the Right Bank (or western side) of the Dnieper River, in present-day Ukraine. The population grew considerably during this time, resulting in settlements being established on plateaus, near major rivers and springs.Their dwellings were built by placing vertical poles in the form of circles or ovals. The construction techniques incorporated log floors covered in clay, wattle-and-daub walls that were woven from pliable branches and covered in clay, and a clay oven, which was situated in the center of the dwelling. As the population in this area grew, more land was put under cultivation. Hunting supplemented the practice of animal husbandry of domestic livestock.

Tools made of flint, rock, clay, wood and bones continued to be used for cultivation and other chores. Much less common than other materials, copper axes and other tools have been discovered that were made from ore mined in Volyn, Ukraine, as well as some deposits along the Dnieper river. Pottery-making by this time had become sophisticated, however they still relied on techniques of making pottery by hand (the potter's wheel was not used yet). Characteristics of the Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery included a monochromic spiral design, painted with black paint on a yellow and red base. Large pear-shaped pottery for the storage of grain, dining plates, and other goods, was also prevalent. Additionally, ceramic statues of female "Goddess" figures, as well as figurines of animals and models of houses dating to this period have also been discovered.

Some scholars have used the abundance of these clay female fetish statues to base the theory that this culture was matriarchal in nature. Indeed, it was partially the archeological evidence from Cucuteni-Trypillian culture that inspired Marija Gimbutas, Joseph Campbell, and some latter 20th century feminists to set forth the popular theory of an Old European culture of peaceful, matriarchal, Goddess-centered Neolithic European societies that were wiped out by patriarchal, Sky Father-worshipping, warlike, Bronze-Age Proto-Indo-European tribes that swept out of The Steppes east of the Black Sea. This theory has been mostly discredited in recent years,[24] but there are still some people who adhere to it, at least to some degree.

Late period (3500-3000 BC)

During the late period the Cucuteni-Trypillian territory expanded to include the Volyn region in northwest Ukraine, the Sluch and Horyn Rivers in northern Ukraine, and along both banks of the Dnieper river near Kiev. Members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture who lived along the coastal regions near the Black Sea came into contact with other cultures. Animal husbandry increased in importance, as hunting diminished; horses also became more important. The community transformed into a patriarchal structure. Outlying communities were established on the Don and Volga rivers in present-day Russia. Dwellings were constructed differently from previous periods, and a new rope-like design replaced the older spiral-patterned designs on the pottery. Different forms of ritual burial were developed where the deceased were interred in the ground with elaborate burial rituals. An increasingly larger number of Bronze Age artifacts originating from other lands were found as the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture drew near.[7]Decline and end

Main article: Decline and end of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture

There is a debate among scholars regarding how the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture took place.According to some proponents of the Kurgan Hypothesis of the origin of Proto-Indo-European, for example the archaeologist Marija Gimbutas in her book "Notes on the chronology and expansion of the Pit-Grave Culture" (1961, later expanded by her and others), the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture came to a violent end in connection with the territorial expansion of the Kurgan Culture. Arguing from archaeological and linguistic evidence, Gimbutas concluded that the people of the Kurgan culture (a term grouping the Pit Grave culture and its predecessors) of the Pontic steppe, being most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, effectively destroyed the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in a series of invasions undertaken during their expansion to the west. Based on this archaeological evidence Gimbutas saw distinct cultural differences between the patriarchal, warlike Kurgan culture and the more peaceful matriarchal Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, which she argued was a significant component of the "Old European cultures" which finally met extinction in a process visible in the progressing appearance of fortified settlements, hillforts, and the graves of warrior-chieftains, as well as in the religious transformation from the matriarchy to patriarchy, in a correlated east-west movement.[25] In this, "the process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation and must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.[26] Accordingly these proponents of the Kurgan Hypothesis hold that this violent clash took place during the Third Wave of Kurgan expansion between 3000-2800 BC, permanently ending the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.

In 1989 Irish-American archaeologist J.P. Mallory in his book "In Search of the Indo-Europeans" summarizing the three existing theories concerning the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, mentions that archaeological findings in the region indicate Kurgan (i.e. Yamna culture) settlements in the eastern part of the Cucuteni-Trypillian area, co-existing for some time with those of the Cucuteni-Trypillian.[5] Artifacts from both cultures found within each of their respective archaeological settlement sites attest to an open trade in goods for a period,[5] though he points out that the archaeological evidence clearly points to what he termed "a dark age," its population seeking refuge in every direction except east. He cites evidence of the refugees having used caves, islands and hilltops (abandoning in the process 600-700 settlements) to argue for the possibility of a gradual transformation rather than a violent onslaught bringing about cultural extinction.[5] The obvious issue with that theory is the limited common historical life-time between the Cucuteni-Trypillian (4800-3000 BC) and the Yamna culture (3600-2300BC); given that the earliest archaeological findings of the Yamna culture (3600-3200 BC) are located in the Volga-Don basin, not in the Dniester and Dnieper area where the cultures came in touch, while the Yamna culture came to its full extension in the Pontic steppe at the earliest around 3000 BC, the time the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ended[27] thus indicating an extremely short survival after coming in contact with the Yamna culture. Another contradicting indication is that the kurgans that replaced the traditional horizontal graves in the area now contain human remains of a fairly diversified skeletal type approximately ten centimeters taller on average than the previous population.[5]

In the 1990s and 2000s, another theory regarding the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture emerged based on climatic change that took place at the end of their culture's existence that is known as the Blytt-Sernander Sub-Boreal phase. Beginning around 3200 BC the earth's climate became colder and drier than it had ever been since the end of the last Ice age, resulting in the worst drought in the history of Europe since the beginning of agriculture.[28] The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture relied primarily on farming, which would have collapsed under these climatic conditions in a scenario similar to the Dust Bowl of the American Midwest in the 1930s.[29] According to The American Geographical Union, "The transition to today's arid climate was not gradual, but occurred in two specific episodes. The first, which was less severe, occurred between 6,700 and 5,500 years ago. The second, which was brutal, lasted from 4,000 to 3,600 years ago. Summer temperatures increased sharply, and precipitation decreased, according to carbon-14 dating. According to that theory, the neighboring Yamna culture people were pastoralists, and were able to maintain their survival much more effectively in drought conditions. This has led some scholars to come to the conclusion that the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ended not violently, but as a matter of survival, converting their economy from agriculture to pastoralism, and becoming integrated into the Yamna culture.[21][28][29][30] However, the Blytt–Sernander approach as a way to identify stages of technology in Europe with specific climate periods is an oversimplification not generally accepted. A conflict with that theoretical possibility is that during the warm Atlantic period, Denmark was occupied by Mesolithic cultures, rather than Neolithic, notwithstanding the climatic evidence. Moreover, the technology stages varied widely globally. To this must be added that the first period of the climate transformation ended some 500 years before the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and the second approximately 1,400 years after.

Economy

Main article: Economy of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Throughout the 2,750 years of its existence, the Cucuteni-Trypillian

culture was fairly stable and static; however, there were changes that

took place. This article addresses some of these changes that have to do

with the economic aspects. These include the basic economic conditions

of the culture, the development of trade, interaction with other

cultures, and the apparent use of barter tokens, an early form of money.Members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture shared common features with other Neolithic societies, including:

- An almost nonexistent social stratification

- Lack of a political elite

- Rudimentary economy, most likely a subsistence or gift economy

- Pastoralists and subsistence farmers

Like other Neolithic societies, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture had almost no division of labor. Although this culture's settlements sometimes grew to become the largest on earth at the time (up to 15,000 people in the largest), there is no evidence that has been discovered of labor specialization. Every household probably had members of the extended family who would work in the fields to raise crops, go to the woods to hunt game and bring back firewood, work by the river to bring back clay or fish, and all of the other duties that would be needed to survive. Contrary to popular belief, the Neolithic people experienced considerable abundance of food and other resources.[4] Since every household was almost entirely self-sufficient, there was very little need for trade. However, there were certain mineral resources that, because of limitations due to distance and prevalence, did form the rudimentary foundation for a trade network that towards the end of the culture began to develop into a more complex system, as is attested to by an increasing number of artifacts from other cultures that have been dated to the latter period.[5]

Toward the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture's existence (from roughly 3000 BC to 2750 BC), copper traded from other societies (notably, from the Balkans) began to appear throughout the region, and members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture began to acquire skills necessary to use it to create various items. Along with the raw copper ore, finished copper tools, hunting weapons and other artifacts were also brought in from other cultures.[4] This marked the transition from the Neolithic to the Eneolithic, also known as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. Bronze artifacts began to show up in archaeological sites toward the very end of the culture. The primitive trade network of this society, that had been slowly growing more complex, was supplanted by the more complex trade network of the Proto-Indo-European culture that eventually replaced the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.[4]

Diet

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was a society of subsistence farmers. Cultivating the soil (using an ard or scratch plough), harvesting crops and tending livestock was probably the main occupation for most people. Typically for a Neolithic culture, the vast majority of their diet consisted of cereal grains. They cultivated club wheat, oats, rye, proso millet, barley and hemp, which were probably ground and baked as unleavened bread in clay ovens or on heated stones in the home. They also grew peas and beans, apricot, cherry plum and wine grapes – though there is no solid evidence that they actually made wine.[31][32] There is also evidence that they may have kept bees.[33]The zooarchaeology of Cucuteni-Trypillian sites indicate that the inhabitants practiced animal husbandry. Their domesticated livestock consisted primarily of cattle, but included smaller numbers of pigs, sheep and goats. There is evidence, based on some of the surviving artistic depictions of animals from Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, that the ox was employed as a draft animal.[31]

Both remains and artistic depictions of horses have been discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites. However, whether these finds are of domesticated or wild horses is debated. Before they were domesticated, humans hunted wild horses for meat. On the other hand, one hypothesis of horse domestication places it in the steppe region adjacent to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture at roughly the same time (4000–3500 BC), so it is possible the culture was familiar with the domestic horse. At this time horses could have been kept both for meat or as a work animal.[34] The direct evidence remains inconclusive.[35]

Hunting supplemented the Cucuteni-Trypillian diet. They used traps to catch their prey, as well as various weapons, including the bow-and-arrow, the spear, and clubs. To help them in stalking game, they sometimes disguised themselves with camouflage.[34] Remains of game species found at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites include red deer, roe deer, aurochs, wild boar, fox and brown bear.[citation needed]

Salt

The earliest known salt works in the world is at Poiana Slatinei, near the village of Lunca in Romania. It was first used in the early Neolithic, around 6050 BCE, by the Starčevo culture, and later by the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the Precucuteni period.[36] Evidence from this and other sites indicates that the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture extracted salt from salt-laden spring-water through the process of briquetage. First, the brackish water from the spring was boiled in large pottery vessels, producing a dense brine. The brine was then heated in a ceramic briquetage vessel until all moisture was evaporated, with the remaining crystallized salt adhering to the inside walls of the vessel. Then the briquetage vessel was broken open, and the salt was scraped from the shards.[37]The provision of salt was a major logistical problem for the largest Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements. As they came to rely upon cereal foods over salty meat and fish, Neolithic cultures had to incorporate supplementary sources of salt into their diet. Similarly, domestic cattle need to be provided with extra sources of salt beyond their normal diet or their milk production is reduced. Cucuteni-Trypillian mega-sites, with a population of likely thousands of people and animals, are estimated to have required between 36,000 and 100,000 kg of salt per year. This was not available locally, and so had to be moved in bulk from distant sources on the western Black Sea coast and in the Carpathian Mountains, probably by river.[38]

Technology and material culture

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is known by its distinctive settlements, architecture, intricately decorated pottery and anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines, which are preserved in archaeological remains. At its peak it was one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world at the time,[5] developing new techniques for ceramic production, housing building and agriculture, and producing woven textiles (although these have not survived and are known indirectly).Settlements

Main articles: Settlements of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, Architecture of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture and House burning of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

In terms of overall size, some of Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, such as Talianki (with a population of 15,000 and covering an area of some 335[39] hectares) in the province of Uman Raion, Ukraine, are as large as (or perhaps even larger than) the more famous city-states of Sumer in the Fertile Crescent, and these Eastern European settlements predate the Sumerian cities by more than half of a millennium.[40]Archaeologists have uncovered an astonishing[peacock term] wealth of artifacts from these ancient ruins. The largest collections of Cucuteni-Trypillian artifacts are to be found in museums in Russia, Ukraine, and Romania, including the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and the Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamţ in Romania. However, smaller collections of artifacts are kept in many local museums scattered throughout the region.[21]

These settlements underwent periodical acts of destruction and re-creation, as they were burned and then rebuilt every 60–80 years. Some scholars[who?] have theorized that the inhabitants of these settlements believed that every house symbolized an organic, almost living, entity. Each house, including its ceramic vases, ovens, figurines and innumerable objects made of perishable materials, shared the same circle of life, and all of the buildings in the settlement were physically linked together as a larger symbolic entity. As with living beings, the settlements may have been seen as also having a life cycle of death and rebirth.[41]

The houses of the Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements were constructed in several general ways:

- Wattle and daub homes.

- Log homes, called (Ukrainian: площадки ploščadki).

- Semi-underground homes called Bordei.

Decorated Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery

Characteristically vessels were elaborately decorated with swirling patterns and intricate designs. Sometimes decorative incisions were added prior to firing, and sometimes these were filled with colored dye to produce a dimensional effect. In the early period, the colors used to decorate pottery were limited to a rusty-red and white. Later, potters added additional colors to their products and experimented with more advanced ceramic techniques.[7] The pigments used to decorate ceramics were based on iron oxide for red hues, calcium carbonate, iron magnetite and manganese Jacobsite ores for black, and calcium silicate for white. The black pigment, which was introduced during the later period of the culture, was a rare commodity: taken from a few sources and circulated (to a limited degree) throughout the region. The probable sources of these pigments were Iacobeni in Romania for the iron magnetite ore and Nikopol in Ukraine for the manganese Jacobsite ore.[42][43] No traces of the iron magnetite pigment mined in the easternmost limit of the Cucuteni-Trypillian region have been found to be used in ceramics from the western settlements, suggesting exchange throughout the entire cultural area was limited. In addition to mineral sources, pigments derived from organic materials (including bone and wood) were used to create various colors.[44]

In the late period of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, kilns with a controlled atmosphere were used for pottery production. These kilns were constructed with two separate chambers—the combustion chamber and the filling chamber— separated by a grate. Temparatures in the combustion chamber could reach 1000–1100 °C but were usually maintained at around 900 °C to achieve a uniform and complete firing of vessels.[42]

Toward the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, as copper became more readily available, advances in ceramic technology leveled off as more emphasis was placed on developing metallurgical techniques.

Ceramic figurines

An anthropomorphic ceramic artifact was discovered during an archaeological dig in 1942 on Cetatuia Hill near Bodeşti, Neamţ County, Romania, which became known as the "Cucuteni Frumusica Dance" (after a nearby village of the same name). It was used as a support or stand, and upon its discovery was hailed as a symbolic masterpiece of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. It is believed that the four stylized feminine silhouettes facing inward in an interlinked circle represented a hora, or ritualistic dance. Similar artifacts were later found in Bereşti and Drăgușeni.Extant figurines excavated at the Cucuteni sites are thought to represent religious artefacts, but their meaning or use is still unknown. Some historians as Gimbutas claim that:

...the stiff nude to be representative of death on the basis that the color white is associated with the bone (that which shows after death). Stiff nudes can be found in Hamangia, Karanovo, and Cucuteni cultures[45]

Textiles

No examples of Cucuteni-Trypillian textiles have yet been found – preservation of prehistoric textiles is rare and the region does not have a suitable climate. However, impressions of textiles are found on pottery sherds (because the clay was placed there before it was fired). These show that woven fabrics were common in Cucuteni-Trypillian society.[46][47] Finds of ceramic weights with drilled holes suggest that these were manufactured with a warp weighted loom.[48] It has also been suggested that these weights, especially "disposable" examples made from poor quality clay and inadequately fired, were used to weigh down fishing nets. These would probably have been frequently lost, explaining their inferior quality.[49]Other pottery sherds with textile impressions, found at Frumusica[disambiguation needed] and Cucuteni, suggest that textiles were also knitted (specifically using a technique known as nalbinding).[50]

Weapons and tools

The following types of tools have been discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites:[citation needed]

| Tool | Typical materials | |

|---|---|---|

| Woodworking | Adzes | Stone |

| Burins | ||

| Scrapers | ||

| Awls | Stone, antler, horn, copper | |

| Gouges/chisels | Stone, bone | |

| Lithic reduction | Pressure flaking tools, e.g. abrasive pieces, plungers, pressing and retouching tools |

Stone |

| Anvils | ||

| Hammerstones | ||

| Soft hammers | Antler, horn | |

| Polishing tools | Bone | |

| Textiles | Knitting needles | Bone |

| Shuttles | ||

| Sewing needles | Bone, copper | |

| Spindles and spindle whorls | Clay | |

| Loom weights | ||

| Farming | Hoes | Antler, horn |

| Ards | ||

| Ground stones/metates and grinding slabs | Stone | |

| Scythes | Flint pieces inlaid into antler or wood blades | |

| Fishing | Harpoons | Bone |

| Fish hooks | Bone, copper | |

| Other/multipurpose | Axes, including double-headed axes, hammer axes and possible battle axes |

Stone, copper |

| Clubs | Stone | |

| Knives and daggers | Stone, bone, copper | |

| Arrow tips | Bone | |

| Handles | ||

| Spatulas | ||

Ritual and religion

Main article: Religion and ritual of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Some Cucuteni-Trypillian communities have been found that contain a

special building located in the center of the settlement, which

archaeologists have identified as sacred sanctuaries. Artifacts have

been found inside these sanctuaries, some of them having been

intentionally buried in the ground within the structure, that are

clearly of a religious nature, and have provided insights into some of

the beliefs, and perhaps some of the rituals and structure, of the

members of this society. Additionally, artifacts of an apparent

religious nature have also been found within many domestic

Cucuteni-Trypillian homes.Many of these artifacts are clay figurines or statues. Archaeologists have identified many of these as fetishes or totems, which are believed to be imbued with powers that can help and protect the people who look after them.[20] These Cucuteni-Trypillian figurines have become known popularly as Goddesses, however, this term is not necessarily accurate for all female anthropomorphic clay figurines, as the archaeological evidence suggests that different figurines were used for different purposes (such as for protection), and so are not all representative of a Goddess.[20] There have been so many of these figurines discovered in Cucuteni-Trypillian sites[20] that many museums in eastern Europe have a sizeable collection of them, and as a result, they have come to represent one of the more readily identifiable visual markers of this culture to many people.

The noted archaeologist Marija Gimbutas based at least part of her famous Kurgan Hypothesis and Old European culture theories on these Cucuteni-Trypillian clay figurines. Her conclusions, which were always controversial, today are discredited by many scholars,[20] but still there are some scholars who support her theories about how Neolithic societies were matriarchal, non-warlike, and worshipped an "earthy" Mother Goddess, but were subsequently wiped out by invasions of patriarchal Indo-European tribes who burst out of the Steppes of Russia and Kazakhstan beginning around 2500 BC, and who worshiped a warlike Sky God.[52] However, Gimbutas' theories have been partially discredited by more recent discoveries and analyses.[5] Today there are many scholars who disagree with Gimbutas, pointing to new evidence that suggests a much more complex society during the Neolithic era than she had been accounting for.[53]

Further information: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

One of the unanswered questions regarding the Cucuteni-Trypillian

culture is the small number of artifacts associated with funerary rites.

Although very large settlements have been explored by archaeologists,

the evidence for mortuary activity is almost invisible. Making a

distinction between the eastern Trypillia and the western Cucuteni

regions of the Cucuteni-Trypillian geographical area, American

archaeologist Douglass W. Bailey writes:There are no Cucuteni cemeteries and the Trypillia ones that have been discovered are very late.[20](p115)The discovery of skulls is more frequent than other parts of the body, however because there has not yet been a comprehensive statistical survey done of all of the skeletal remains discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, precise post excavation analysis of these discoveries cannot be accurately determined at this time. Still, many questions remain concerning these issues, as well as why there seems to have been no male remains found at all.[54] The only definite conclusion that can be drawn from archeological evidence is that in the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, in the vast majority of cases, the bodies were not formally deposited within the settlement area.[20](p116)

Vinča-Turdaş script

Main articles: Symbols and proto-writing of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and Vinča symbols

The mainstream academic view holds that writing first appeared during the Sumerian civilization in southern Mesopotamia, around 3300–3200 BC. in the form of the Cuneiform script.

This first writing system did not suddenly appear out of nowhere, but

gradually developed from less stylized pictographic systems that used ideographic and mnemonic symbols that contained meaning, but did not have the linguistic flexibility of the natural language writing system that the Sumerians first conceived. These earlier symbolic systems have been labeled as proto-writing, examples of which have been discovered in a variety of places around the world, some dating back to the 7th millennium BC.[55]-

One of the three Tărtăria tablets, dated 5300 BC

-

One of the Gradeshnitsa tablets

Beginning in 1875 up to the present, archaeologists have found more than a thousand Neolithic era clay artifacts that have examples of symbols similar to the Vinča script scattered widely throughout south-eastern Europe. This includes the discoveries of what appear to be barter tokens, which were used as an early form of currency. Thus it appears that the Vinča or Vinča-Turdaş script is not restricted to just the region around Belgrade, which is where the Vinča culture existed, but that it was spread across most of southeastern Europe, and was used throughout the geographical region of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. As a result of this widespread use of this set of symbolic representations, historian Marco Merlini has suggested that it be given a name other than the Vinča script, since this implies that it was only used among the Vinča culture around the Pannonian Plain, at the very western edge of the extensive area where examples of this symbolic system have been discovered. Merlini has proposed naming this system the Danube Script, which some scholars have begun to accept.[55] However, even this name change would not be extensive enough, since it does not cover the region in Ukraine, as well as the Balkans, where examples of these symbols are also found. Whatever name is used, however (Vinča script, Vinča-Tordos script, Vinča symbols, Danube script, or Old European script), it is likely that it is the same system.[55]

Archaeogenetics

Further information: Archaeogenetics of Europe

A 2010 study analyzed mtDNA recovered from Cucuteni-Trypillian human osteological remains found in the Verteba Cave (on the bank of the Seret River, Ternopil Oblast, Ukraine). It revealed that seven of the individuals whose remains where analysed belonged to the pre-HV branch of the R haplogroup, two to haplogroup HV, two to haplogroup H, one to haplogroup J, and one to T4 haplogroup, the latter also being the oldest sample of the set.The authors conclude that the population living around Verteba Cave was fairly heterogenous, but that the wide chronological age of the specimens might indicate that the heterogeneity might have been due to natural population flow during this timeframe. The authors also link the pre-HV and HV/V haplogroups with European Paleolithic populations, and consider the T and J haplogroups as hallmarks of Neolithic demic intrusions from the South-East (the North-Pontic region) rather than from the West (i.e. the Linear Pottery culture).[56]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)