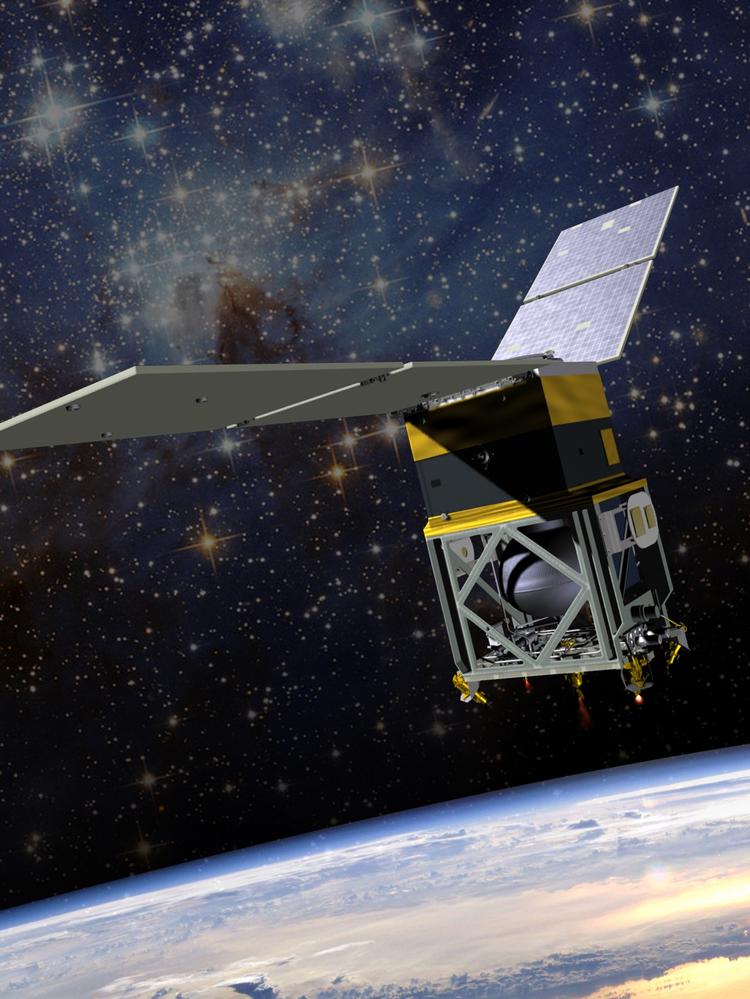

This satellite will test the new "green propellant" engines developed by Aerojet… more

A pioneering

Seattle-area outer space company has developed a new kind of deep space

rocket engine that is 50 percent more fuel efficient than current

designs.

And as a bonus, the fuel the new Aerojet Rocketdyne engine uses isn’t toxic.

Aerojet

Rocketdyne has for decades in Redmond built small rocket engines to

guide satellites and deep space probes, but most of those have been

fueled by hydrazine. This fuel is so toxic that people handling it must

wear full environmental suits.

Now, in building

new engines that can accommodate "green" rocket fuel, the 400-person

Redmond unit of $1.6 billion Aerojet Rocketdyne Holdings Inc. (NYSE:

AJRD), is in a strong position to build many of the new engines in the

future.

At least at

first, the engines are likely to be used by companies, such as

Tukwila-based SpaceFlight Industries and Redmond-based Planetary

Resources, on the guidance systems for smaller satellites that get sent

to space.

If it becomes popular with satellite companies, the technology could help support the region's growing outer space industry.

“This is absolutely a promising technology,” said Jeff Foust, senior staff writer for Space News, who reported on Aerojet project. “Aerojet is well positioned with the technology to apply that in the future.”

The new so called "AF-M315E fuel," which was developed by the U.S. Air Force, can be handled by people in shirtsleeves, said Roger Myers, executive director of advanced in-space programs for Aerojet Rocketdyne in Redmond.

“Hydrazine has

many useful properties for spacecraft propulsion, and finding a

non-toxic alternative was a big challenge for the last 25 years,” Myers

said. “We have partnered with the Air Force and NASA for the last 15 years to develop the rocket and propulsion system technologies to use that propellant on actual spacecraft.”

In a release, NASA referred to the new fuel as “green,” primarily because it isn’t extremely poisonous.

While green

doesn’t mean the new fuel is made from organic soybeans, the fact that

it’s not virulently toxic is a big step, Foust said.

“Hydrazine is really difficult to handle,” he said.

But the

technology has come with challenges, specifically that the new engines

operate “several hundred degrees” hotter than hydrazine engines, Myers

said.

Developing the

needed metal alloys and manufacturing techniques was a key breakthrough

for Aerojet Rocketdyne, but the new engines still have to be proven in

the rigors of outer space.

NASA

plans to do just that in 2016, when it tests Aerojet Rocketdyne engines

with the AF-M315E fuel in a test satellite orbiting Earth.

“That’s the

whole purpose of this mission,” Foust said. “It’s to provide an in-space

demonstration of this propulsion system, and see how well it works, and

if there are any other issues with this aspect of the spacecraft.”

No comments:

Post a Comment