BERLIN – Scientists say ancient DNA samples indicate massive migration to Europe from the east took place some 4,500 years ago.

The findings support the theory that some Indo-European languages, such as Germanic and Slavic, were introduced by people from the steppe.

Researchers from Europe, the United States and Australia analyzed the DNA of 69 people who lived between 8,000 and 3,000 years ago. According to their research, published Monday in the journal Nature, genes from the Yamnaya who lived north of the Black and Aral Seas appeared in what is now northern Germany some four-and-one half millennia ago.

The researchers say since major language replacements are believed to require large-scale migration, the huge influx of ancient steppe DNA still in many present-day Europeans could account for the rise of Indo-European languages.

Poltavka culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Bronze Age |

|

|---|---|

| ↑ Neolithic | |

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

South Asia (c. 3000–1200 BC)

Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

China (c. 2000–700 BC)

|

|

| arsenical bronze writing, literature sword, chariot |

|

| ↓Iron age |

Poltavka culture, 2700—2100 BC, an early to middle Bronze Age archaeological culture of the middle Volga from about where the Don-Volga canal begins up to the Samara bend, with an easterly extension north of present Kazakhstan along the Samara River valley to somewhat west of Orenburg.

It is like the Catacomb culture preceded by the Yamna culture, while succeeded by the Sintashta culture. It seems to be seen as an early manifestation of the Srubna culture. There is evidence of influence from the Maykop culture to its south.

The only real things that distinguish it from the Yamna culture are changes in pottery and an increase in metal objects. Tumulus inhumations continue, but with less use of ochre.

It was preceded by the Yamna culture and succeeded by the Srubna and Sintashta culture. It is presumptively early Indo-Iranian (Proto-Indo-Iranian).

Sintashta

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sintashta is situated in the steppe just east of the Ural Mountains. The site is named for the adjacent Sintashta River, a tributary to the Tobol. The shifting course of the river over time has destroyed half of the site, leaving behind thirty one of the approximately fifty or sixty houses in the settlement.[3]

The settlement consisted of rectangular houses arranged in a circle 140 m in diameter and surrounded by a timber-reinforced earthen wall with gate towers and a deep ditch on its exterior. The fortifications at Sintashta and similar settlements such as Arkaim were of unprecedented scale for the steppe region. There is evidence of copper and bronze metallurgy taking place in every house excavated at Sintashta, again an unprecedented intensity of metallurgical production for the steppe.[3] Early Abashevo culture ceramic styles strongly influenced Sintashta ceramics.[4] Due to the assimilation of tribes in the region of the Urals, such as the Pit-grave, Catacomb, Poltavka, and northern Abashevo into the Novokumak horizon, it would seem inaccurate to provide Sintashta with a purely Aryan attribution.[5] In the origin of Sintashta, the Abashevo culture would play an important role.[4]

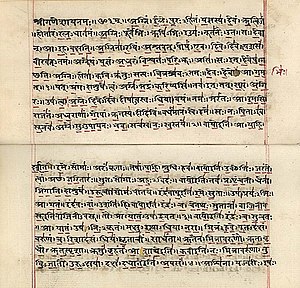

Five cemeteries have been found associated with the site, the largest of which (known as Sintashta mogila or SM) consisted of forty graves. Some of these were chariot burials, producing the oldest known chariots in the world. Others included horse sacrifices—up to eight in a single grave—various stone, copper and bronze weapons, and silver and gold ornaments. The SM cemetery is overlain by a very large kurgan of a slightly later date. It has been noted that the kind of funerary sacrifices evident at Sintashta have strong similarities to funerary rituals described in the Rig Veda, an ancient Indian religious text often associated with the Proto-Indo-Iranians.[3]

Radiocarbon dates from the settlement and cemeteries span over a millennium, suggesting an earlier occupation belonging to the Poltavka culture. The majority the dates, however, are around 2100–1800 BC, which points at a main period of occupation of the site consistent with other settlements and cemeteries of the Sintashta culture.[3]

Sintashta culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Period | Bronze Age | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dates | 2100–1800 BCE | |||||||

| Type site | Sintashta | |||||||

| Major sites | Arkaim Petrovka |

|||||||

| Characteristics | Extensive copper and bronze metallurgy Fortified settlements Elaborate weapon burials Earliest known chariots |

|||||||

| Preceded by | Poltavka culture, Abashevo culture |

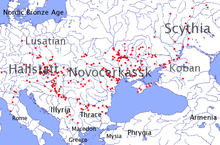

Map of the approximate maximal extent of the Andronovo culture. The

formative Sintashta-Petrovka culture is shown in darker red. The

location of the earliest spoke-wheeled chariot finds is indicated in purple. Adjacent and overlapping cultures (Afanasevo culture, Srubna culture, BMAC) are shown in green.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

Because of the difficulty of identifying the remains of Sintashta sites beneath those of later settlements, the culture was only recently distinguished from the Andronovo culture.[2] It is now recognised as a separate entity forming part of the 'Andronovo horizon'.[1]

Contents

Origin

The Sintashta culture emerged from the interaction of two antecedent cultures. Its immediate predecessor in the Ural-Tobol steppe was the Poltavka culture, an offshoot of the cattle-herding Yamnaya horizon that moved east into the region between 2800 and 2600 BCE. Several Sintashta towns were built over older Poltovka settlements or close to Poltovka cemeteries, and Poltovka motifs are common on Sintashta pottery. Sintashta material culture also shows the influence of the late Abashevo culture, a collection of settlements in the forest steppe zone north of the Sintashta region that were also predominantly pastoralist.[6] The first Sintashta settlements appeared around 2100 BCE, during a period of climatic change that saw the already arid Kazakh steppe region become even more cold and dry. The marshy lowlands around the Ural and upper Tobol rivers, previously favoured as winter refuges, became increasingly important for survival. Under these pressures both Poltovka and Abashevo herders settled permanently in river valley strongholds, eschewing more defensible hill-top locations.[7] The Abashevo culture was already marked by endemic intertribal warfare;[8] intensified by ecological stress and competition for resources in the Sintashta period, this drove the construction of fortifications on an unprecedented scale and innovations in military technique such as the invention of the war chariot. Increased competition between tribal groups may also explain the extravagant sacrifices seen in Sintashta burials, as rivals sought to outdo one another in acts of conspicuous consumption analogous to the North American potlatch tradition.[7]Metal production

The Sintashta economy came to revolve around copper metallurgy. Copper ores from nearby mines (such as Vorovskaya Yama) were taken to Sintashta settlements to be processed into copper and arsenical bronze. This occurred on an industrial scale: all the excavated buildings at the Sintashta sites of Sintashta, Arkaim and Ust'e contained the remains of smelting ovens and slag.[7] Much of this metal was destined for export to the cities of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC) in Central Asia. The metal trade between Sintashta and the BMAC for the first time connected the steppe region to the ancient urban civilisations of the Near East: the empires and city-states of Iran and Mesopotamia provided an almost bottomless market for metals. These trade routes later became the vehicle through which horses, chariots and ultimately Indo-Iranian-speaking people entered the Near East from the steppe.[9][10]Ethnic and linguistic identity

The people of the Sintashta culture are thought to have spoken Proto-Indo-Iranian, the ancestor of the Indo-Iranian language family. This identification is based primarily on similarities between sections of the Rig Veda, an Indian religious text which includes ancient Indo-Iranian hymns recorded in Vedic Sanskrit, with the funerary rituals of the Sintashta culture as revealed by archaeology.[11] There is however linguistic evidence of a list of common vocabulary between Finno-Ugric and Indo-Iranian languages. While its origin as a creole of different tribes in the Ural region may make it inaccurate to ascribe the Sintashta culture exclusively to Indo-Iranian ethnicity, interpreting this culture as a blend of two cultures with two distinct languages is a reasonable hypothesis based on the evidence.[12]See also

Abashevo culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Bronze Age |

|---|

| ↑ Neolithic |

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

South Asia (c. 3000–1200 BC)

Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

China (c. 2000–700 BC)

|

| arsenical bronze writing, literature sword, chariot |

| ↓Iron age |

The Abashevo culture is a later Bronze Age (ca. 2500–1900 BCE) archaeological culture found in the valleys of the Volga and Kama River north of the Samara bend and into the southern Ural Mountains. It receives its name from the village of Abashevo in Chuvashia. Artifacts are kurgans and remnants of settlements. The Abashevo was the easternmost of the Russian forest zone cultures that descended from Corded Ware ceramic traditions. The Abashevo culture played a significant role in the origin of the Sintashta culture.[1] The Abashevo culture does not pertain to the Andronovo culture and genetically belongs to the circle of Central European cultures of the Fatyanovo culture type corded ware ceramics.[2]

The economy was mixed agriculture. Cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as other domestic animals were kept. Horses were evidently used, inferred by cheek pieces typical of neighboring steppe cultures.[3] The population of Sintashta derived their stock-breeding from Abashevo, although the role of the pig shrinks sharply.[4]

It follows the Yamna culture and Balanovo culture[5] in its inhumation practices in tumuli. Flat graves were also a component of the Abashevo culture burial rite,[6] as in the earlier Fatyanovo culture.[7] Grave offerings are scant, little more than a pot or two. Some graves show evidence of a birch bark floor and a timber construction forming walls and roof.[8]

There is evidence of copper smelting, and the culture would seem connected to copper mining activities in the southern Urals. The Abashevo culture was an important center of metallurgy[9] and stimulated the formation of Sintashta metallurgy.[10]

The Abashevo ethno-linguistic identity is a subject of speculation, although it likely reflected a merger of the earlier Iranian steppe Poltavka culture, an extension of Fatyanovo-Balanovo traditions,[11] and contacts with speakers of Uralic; Abashevo was likely the area in which some loan-words entered Uralic. The skulls of the Abashevo differ[how?] from those of the Timber Grave culture, early Catacomb culture, or the Potapovka culture.[12] Abashevo probably witnessed a bilingual population undergo a process of assimilation.[13] Some members of the hunter-gatherer Volosovo culture were apparently also absorbed into the Abashevo populace, as corded-impressed Abashevo pottery has been found alongside comb-stamped Volosovo ceramics at archaeological sites  : sometimes even in the same structure.[14]

Abashevo occupied part of the area of the earlier Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture, the eastern variant of the earlier Corded Ware culture, but whatever relationship there is between the two cultures is uncertain. The pre-eminent expert on the Abashevo culture, A. Pryakhin, concluded that it originated from contacts between Fatyanovo / Balanovo and Catacomb / Poltavka peoples in the southern forest-steppe.[15] Early Abashevo ceramic styles strongly influenced Sintashta ceramics.[16]

It was preceded by the Yamna culture and succeeded by the Srubna culture and the Sintashta culture.[17]

Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture

Fatyanovo-Balanovo culture is shown in pink.

| Bronze Age |

|---|

| ↑ Neolithic |

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

South Asia (c. 3000–1200 BC)

Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

China (c. 2000–700 BC)

|

| arsenical bronze writing, literature sword, chariot |

| ↓Iron age |

The Fatyanovo–Balanovo culture, 3200 BC–2300 BC, is an eastern extension of the Corded Ware culture into Russia.

It runs from Lake Pskov in the west to the middle Volga in the east, with its northern reach in the valley of the upper Volga. It is really two cultures, the Fatyanovo in the west, the Balanovo in the east. The Fatyanovo culture emerged at the northeastern edge of the Middle Dnieper culture, and probably was derived from an early variant of the Middle Dnieper culture.[1]

Fatyanovo migrations correspond to regions with hydronyms of a Baltic language dialect mapped by linguists as far as the Oka river and the upper Volga. Spreading eastward down the Volga they discovered the copper ores of the western Ural foothills, and started long term settlements in lower Kama river region. The Balanovo culture occupied the region of the Kama–Vyatka–Vetluga interfluves[2] where metal resources (local copper sandstone deposits[3]) of the region were exploited.[4]

Fatyanovo ceramics show mixed Corded Ware / Globular Amphorae traits. The later Abashevo culture pottery looked somewhat like Fatyanovo-Balanovo Corded Ware, but Abashevo kurgans were unlike Fatyanovo flat cemeteries, although flat graves[5] were a recognizable component of the Abashevo burial rite. Balanovo burials (like the Middle Dnieper culture[6]) were both of the flat and kurgan type, containing individual and also mass graves.[7]

Settlements are scant, and bear evidence of a degree of fortification. The villages were usually situated on the high hills of the riverbanks, consisting of several above-ground houses built from wooden logs with saddle roofs, and also joined by passages.[8] The economy seems to be quite mobile, but then we are cautioned that domestic swine are found, which suggests something other than a mobile society. The Fatyanovo culture is viewed as introducing an economy based on domestic livestock (sheep, cattle, horse & dog) into the forest zone of Russia.[9] The Balanovo also used draught cattle and two wheeled wagons.[10]

As is usual with such ancient cultures, our main knowledge comes from their inhumations. Shaft graves were evident, which might be lined with wood. The deceased were wrapped in animal skins or birch bark and placed into wooden burial chambers in subterranean rectangular pits.[11] The interments are otherwise in accord with Corded Ware practices, with males resting on their right side and females on their left.[12] Local metal objects of a Central European provenance type were present. Copper ornaments and tools have been found in Balanovo burials. Burial goods depended on sex, age, and social position. Copper axes primarily accompanied persons of high social position, stone axe-hammers were given to men, flint axes to children and women. Amulets are frequently found in the graves[13] as well as metal working implements.[14]

The theory for an intrusive culture is based upon the physical type of the population, flexed burial under barrows, the presence of battle-axes and ceramics. There are similarities between Fatyanovo and Catacomb culture stone battle-axes.[15] The Volosovo culture of indigenous forest foragers was different in its ceramics, economy, and mortuary practices. It dispersed when the Fatyanovo people pushed into the Upper and Middle Volga basin.[16] Ceramic finds indicate Balanovo coexisted with the Finno-Permic Volosovo people (mixed Balanovo-Volosovo sites), and also displace them.[17] Note that the ethnic and linguistic attribution of the Volosovo culture is uncertain; Häkkinen maintains that their language was neither Uralic nor Indo-European, but a substratum to Finno-Permic.[18] The cultures of the Prikamsky subarea in the Late Bronze Age continued preceding traditions in pottery, house designs, and stable animal husbandry with the breeding of horse, cattle, and to a lesser extent, pigs and sheep. Scholars interpret some of these cultures with stages in the development of the proto-Permian language.[19] Some have argued that this culture represents the acculturation of Pit-Comb Ware culture people of this area from contacts with Corded Ware agriculturists in the West.[20] It does not seem to represent a northern extension of the Indo-European Yamna culture horizon further south.

Historical sources mention a people inhabiting the region of the earlier Fatyanovo region. The Hypatian Codex of Chronicles mentions that in 1147 the Prince of Rostov-Suzdal defeated the Golyad' (Голядь) who lived by the River Porotva. The Protva is a tributary of the Oka river near Moscow, where there is a wealth of Baltic hydronyms.

Middle Dnieper culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Bronze Age |

|---|

| ↑ Neolithic |

Near East (c. 3300–1200 BC)

South Asia (c. 3000–1200 BC)

Europe (c. 3200–600 BC)

China (c. 2000–700 BC)

|

| arsenical bronze writing, literature sword, chariot |

| ↓Iron age |

Geographically it is directly behind the area occupied by the Globular Amphora culture (south and east), and while commencing a little later and lasting a little longer, it is otherwise contemporaneous with it.

More than 200 sites are attested to, mostly as barrow inhumations under tumuli; some of these burials are secondary depositions into Yamna-era kurgans. Grave goods included pottery and stone battle-axes. There is some evidence of cremation in the northerly area. Settlements seem difficult to define; the economy was much like that of the Yamna and Corded Ware cultures, semi-to-fully-nomadic pastoralism.[1]

Within the context of the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas, this culture is a major center for migrations (or invasions, if you prefer) from the Yamna culture and its immediate successors into Northern and Central Europe.

It has been argued that the area where the Middle Dnieper culture is situated would have provided a better migration route for steppe tribes along the Pripyat tributary of the Dnieper and perhaps provided the cultural bridge between Yamna and Corded Ware cultures. This area has also been a classic invasion route as seen historically with the armies of the Mongol Golden Horde (moving east to west from the steppes) and Napoleon Bonaparte (moving west to east from Europe).[2] On the other hand the Middle-Dnieper culture has been viewed as a contact zone between Yamnaya steppe tribes and occupants of the forest steppe zone possibly signaling communications between pre-Indo-Iranian speakers and pre-Balto-Slavs as interpreted by an exchange of material goods evident in the archaeological record sans migration.[3]

Sredny Stog culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Sredny Stog culture is a pre-kurgan archaeological culture, named after the Russian term for the Dnieper river islet of Seredny Stih, Ukraine, where it was first located, dating from the 5th millennium BC. It was situated across the Dnieper river on both its shores, with sporadic settlements to the west and east.[1] One of the best known sites associated with this culture is Dereivka,

located on the right bank of the Omelnik, a tributary of the Dnieper,

and is the most impressive site within the Sredny Stog culture complex,

being about 2,000 square meters in area.

The Sredny Stog culture seems to have had contact with the agricultural Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the west and was a contemporary of the Khvalynsk culture.Overview

In its three largest cemeteries, Alexandria (39 individuals), Igren (17) and Dereivka (14), evidence of inhumation in flat graves (ground level pits) has been found.[2] This parallels the practise of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, and is in contrast with the later Yamna culture, which practiced tumuli burials, according to the Kurgan hypothesis. In Sredny Stog culture, the deceased were laid to rest on their backs with the legs flexed. The use of ochre in the burial was practiced, as with the kurgan cultures. For this and other reasons, Yuri Rassamakin suggests that the Sredny Stog culture should be considered as an areal term, with at least four distinct cultural elements co-existing inside the same geographical area.

The expert Dmytro Telegin has divided the chronology of Sredny Stog into two distinct phases. Phase II (ca. 4000–3500 BC) used corded ware pottery which may have originated there, and stone battle-axes of the type later associated with expanding Indo-European cultures to the West. Most notably, it has perhaps the earliest evidence of horse domestication (in phase II), with finds suggestive of cheek-pieces (psalia).

In the context of the modified Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas, this pre-kurgan archaeological culture could represent the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language. The culture ended at around 3500 BC, when Yamna culture expanded westward replacing Sredny Stog, and coming into direct contact with the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the western Ukraine.

Yamna culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Yamna culture 3500-2000 BC.

Approximate culture extent c. 3200-2300 BC.

The Yamna culture (Ukrainian: Ямна культура, Russian: Ямная культура, "Pit [Grave] Culture", from Russian/Ukrainian яма, "pit") is a late copper age/early Bronze Age culture of the Southern Bug/Dniester/Ural region (the Pontic steppe), dating to the 36th–23rd centuries BC. The name also appears in English as Pit Grave Culture or Ochre Grave Culture.

The culture was predominantly nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers and a few hillforts.[1]

The Yamna culture was preceded by the Sredny Stog culture, Khvalynsk culture and Dnieper-Donets culture, while succeeded by the Catacomb culture and the Srubna culture.

Contents

[hide]Characteristics

Characteristic for the culture are the inhumations in kurgans (tumuli) in pit graves with the dead body placed in a supine position with bent knees. The bodies were covered in ochre. Multiple graves have been found in these kurgans, often as later insertions.[citation needed]Significantly, animal grave offerings were made (cattle, sheep, goats and horse), a feature associated with Proto-Indo-Europeans .[2]

The earliest remains in Eastern Europe of a wheeled cart were found in the "Storozhova mohyla" kurgan (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, excavated by Trenozhkin A.I.) associated with the Yamna culture.

Spread and identity

The Yamna culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas. It is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, along with the preceding Sredny Stog culture, now that archaeological evidence of the culture and its migrations has been closely tied to the evidence from linguistics.[3]Pavel Dolukhanov argues that the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various local Bronze Age cultures, representing "an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures", which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.[4]

It is said to have originated in the middle Volga based Khvalynsk culture and the middle Dnieper based Sredny Stog culture.[citation needed] In its western range, it is succeeded by the Catacomb culture; in the east, by the Poltavka culture and the Srubna culture.

Genetics

DNA from the remains of nine individuals associated with the Yamna culture from Samara Oblast and Orenburg Oblast has been analyzed. The remains have been dated to 2700-3339 BCE. Y-chromosome sequencing revealed that one of the individuals belonged to haplogroup R1b1-P25 (the subclade could not be determined), one individual belonged to haplogroup R1b1a2a-L23 (and to neither the Z2103 nor the L51 subclades), and five individuals belonged to R1b1a2a2-Z2103. The individuals belonged to mtDNA haplogroups U4a1, W6, H13a1a1a, T2c1a2, U5a1a1, H2b, W3a1a and H6a1b. A recent genome wide association study revealed The autosomal DNA characteristics are very close to the Corded Ware culture and estimated a 73% ancestral contribution from the Yamna into the Corded Ware. The same study estimated a 45-50% ancestral contribution of the Yamna into modern Central & Northern Europeans, and a 20-30% contribution into modern Southern Europeans [excluding Sardinians].[5]Artifacts

From the Hermitage Museum collections

Proto-Indo-Europeans

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Proto-Indo-Europeans were the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language (PIE), a reconstructedprehistoric language of Eurasia.

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from the linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who posit an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities—a tribe in the broad sense.

The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship places them in the forest-steppe zone immediately to the north of the western end of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe. Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BCE) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BC), and suggest alternative location hypotheses.

By the early second millennium BC, offshoots of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had expanded far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (Mycenaean Greece), Western Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamna culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasevo culture).[1]

Knowledge of them comes chiefly from the linguistic reconstruction, along with material evidence from archaeology and archaeogenetics. According to some archaeologists, PIE speakers cannot be assumed to have been a single, identifiable people or tribe, but were a group of loosely related populations ancestral to the later, still partially prehistoric, Bronze Age Indo-Europeans. This view is held especially by those archaeologists who posit an original homeland of vast extent and immense time depth. However, this view is not shared by linguists, as proto-languages, like all languages before modern transport and communication, occupied small geographical areas over a limited time span, and were spoken by a set of close-knit communities—a tribe in the broad sense.

The Proto-Indo-Europeans likely lived during the late Neolithic, or roughly the 4th millennium BC. Mainstream scholarship places them in the forest-steppe zone immediately to the north of the western end of the Pontic-Caspian steppe in Eastern Europe. Some archaeologists would extend the time depth of PIE to the middle Neolithic (5500 to 4500 BCE) or even the early Neolithic (7500 to 5500 BC), and suggest alternative location hypotheses.

By the early second millennium BC, offshoots of the Proto-Indo-Europeans had expanded far and wide across Eurasia, including Anatolia (Hittites), the Aegean (Mycenaean Greece), Western Europe (Corded Ware culture), the edges of Central Asia (Yamna culture), and southern Siberia (Afanasevo culture).[1]

Contents

Culture

Main articles: Proto-Indo-European religion and Proto-Indo-European society

The following basic traits of the Proto-Indo-Europeans and their

environment are widely agreed upon but still hypothetical due to their

reconstructed nature:

- stockbreeding and animal husbandry, including domesticated cattle, horses, and dogs[2]

- agriculture and cereal cultivation, including technology commonly ascribed to late-Neolithic farming communities, e.g., the plow[3]

- a climate with winter snow[4]

- transportation by or across water[2]

- the solid wheel,[2] used for wagons, but not yet chariots with spoked wheels[5]

- worship of a sky god,[3] *dyeus ph2tēr (lit. "sky father"; > Ancient Greek Ζεύς (πατήρ) / Zeus (patēr); *dieu-ph2tēr > Latin Jupiter; Illyrian Deipaturos)[6][7]

- oral heroic poetry or song lyrics that used stock phrases such as imperishable fame[2] and wine-dark sea

- a patrilineal kinship-system based on relationships between men[2]

The Proto-Indo-Europeans had a patrilineal society, relying largely on agriculture, but partly on animal husbandry, notably of cattle and sheep. They had domesticated horses – *eḱwos (cf. Latin equus). The cow (*gwous)

played a central role, in religion and mythology as well as in daily

life. A man's wealth would have been measured by the number of his

animals (small livestock), *peḱus (cf. English fee, Latin pecunia).

They practiced a polytheisticreligion centered on sacrificialrites, probably administered by a priestly caste. Burials in barrows or tomb chambers apply to the Kurgan culture, in accordance with the original version of the Kurgan hypothesis, but not to the previous Sredny Stog culture, which is also generally associated with PIE. Important leaders would have been buried with their belongings in kurgans, and possibly also with members of their households or wives (human sacrifice, suttee).

Many Indo-European societies know a threefold division of priests, a warrior class, and a class of peasants or husbandmen. Georges Dumézil has suggested such a division for Proto-Indo-European society.

If there were a separate class of warriors, it probably consisted of single young men. They would have followed a separate warrior code unacceptable in the society outside their peer-group. Traces of initiation rites in several Indo-European societies suggest that this group identified itself with wolves or dogs (see also Berserker, werewolf).

As for technology, reconstruction indicates a culture of the late Neolithic bordering on the early Bronze Age, with tools and weapons very likely composed of "natural bronze" (i.e., made from copper ore naturally rich in silicon or arsenic). Silver and gold were known, but not silver smelting (as PIE has no word for lead, a by-product of silver smelting), thus suggesting that silver was imported. Sheep were kept for wool, and textiles were woven. The wheel was known, certainly for ox-drawn wagons.

They practiced a polytheisticreligion centered on sacrificialrites, probably administered by a priestly caste. Burials in barrows or tomb chambers apply to the Kurgan culture, in accordance with the original version of the Kurgan hypothesis, but not to the previous Sredny Stog culture, which is also generally associated with PIE. Important leaders would have been buried with their belongings in kurgans, and possibly also with members of their households or wives (human sacrifice, suttee).

Many Indo-European societies know a threefold division of priests, a warrior class, and a class of peasants or husbandmen. Georges Dumézil has suggested such a division for Proto-Indo-European society.

If there were a separate class of warriors, it probably consisted of single young men. They would have followed a separate warrior code unacceptable in the society outside their peer-group. Traces of initiation rites in several Indo-European societies suggest that this group identified itself with wolves or dogs (see also Berserker, werewolf).

As for technology, reconstruction indicates a culture of the late Neolithic bordering on the early Bronze Age, with tools and weapons very likely composed of "natural bronze" (i.e., made from copper ore naturally rich in silicon or arsenic). Silver and gold were known, but not silver smelting (as PIE has no word for lead, a by-product of silver smelting), thus suggesting that silver was imported. Sheep were kept for wool, and textiles were woven. The wheel was known, certainly for ox-drawn wagons.

History of research

Researchers have made many attempts to identify particular

prehistoric cultures with the Proto-Indo-European-speaking peoples, but

all such theories remain speculative. Any attempt to identify an actual

people with an unattested language depends on a sound reconstruction of

that language that allows identification of cultural concepts and

environmental factors associated with particular cultures (such as the

use of metals, agriculture vs. pastoralism, geographically distinctive

plants and animals, etc.).

The scholars of the 19th century who first tackled the question of the Indo-Europeans' original homeland (also called Urheimat, from German), had essentially only linguistic evidence. They attempted a rough localization by reconstructing the names of plants and animals (importantly the beech and the salmon) as well as the culture and technology (a Bronze Age culture centered on animal husbandry and having domesticated the horse). The scholarly opinions became basically divided between a European hypothesis, positing migration from Europe to Asia, and an Asian hypothesis, holding that the migration took place in the opposite direction.

In the early 20th century, the question became associated with the expansion of a supposed "Aryan race".[8] The question remains contentious within some flavours of ethnic nationalism (see also Indigenous Aryans).

A series of major advances occurred in the 1970s due to the convergence of several factors. First, the radiocarbon dating method (invented in 1949) had become sufficiently inexpensive to be applied on a mass scale. Through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), pre-historians could calibrate radiocarbon dates to a much higher degree of accuracy. And finally, before the 1970s, parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia had been off limits to Western scholars, while non-Western archaeologists did not have access to publication in Western peer-reviewed journals. The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars.

The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2014 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is not universally accepted.[9][10] It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic.[citation needed] A minority of scholars prefers the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support.[citation needed]

[update]

The scholars of the 19th century who first tackled the question of the Indo-Europeans' original homeland (also called Urheimat, from German), had essentially only linguistic evidence. They attempted a rough localization by reconstructing the names of plants and animals (importantly the beech and the salmon) as well as the culture and technology (a Bronze Age culture centered on animal husbandry and having domesticated the horse). The scholarly opinions became basically divided between a European hypothesis, positing migration from Europe to Asia, and an Asian hypothesis, holding that the migration took place in the opposite direction.

In the early 20th century, the question became associated with the expansion of a supposed "Aryan race".[8] The question remains contentious within some flavours of ethnic nationalism (see also Indigenous Aryans).

A series of major advances occurred in the 1970s due to the convergence of several factors. First, the radiocarbon dating method (invented in 1949) had become sufficiently inexpensive to be applied on a mass scale. Through dendrochronology (tree-ring dating), pre-historians could calibrate radiocarbon dates to a much higher degree of accuracy. And finally, before the 1970s, parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia had been off limits to Western scholars, while non-Western archaeologists did not have access to publication in Western peer-reviewed journals. The pioneering work of Marija Gimbutas, assisted by Colin Renfrew, at least partly addressed this problem by organizing expeditions and arranging for more academic collaboration between Western and non-Western scholars.

The Kurgan hypothesis, as of 2014 the most widely held theory, depends on linguistic and archaeological evidence, but is not universally accepted.[9][10] It suggests PIE origin in the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the Chalcolithic.[citation needed] A minority of scholars prefers the Anatolian hypothesis, suggesting an origin in Anatolia during the Neolithic. Other theories (Armenian hypothesis, Out of India theory, Paleolithic Continuity Theory, Balkan hypothesis) have only marginal scholarly support.[citation needed]

Urheimat hypotheses

Main article: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

See also: Indo-European migrations

Scheme of Indo-European migrations from ca. 4000 to 1000 BCE according to the Kurgan hypothesis. The magenta area corresponds to the assumed Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture).

The red area corresponds to the area which may have been settled by

Indo-European-speaking peoples up to ca. 2500 BCE; the orange area to

1000 BCE.[11]

There has been a great variety of ideas of the location of the first

speakers of Proto-Indo-European, few of which have survived scrutiny by

academic specialists in Indo-European studies sufficiently well to be

included in modern academic debate.[12] The three remaining contenders are summarized here.

In the 20th century, Marija Gimbutas created the Kurgan hypothesis. The name is taken from the kurgans (burial mounds) of the Eurasian steppes. The hypothesis is that the Indo-Europeans were a nomadic tribe of the Pontic-Caspian steppe (now Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia) and expanded in several waves during the 3rd millennium BC. Their expansion coincided with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see battle-axe people), they subjugated the peaceful European Neolithic farmers of Gimbutas' Old Europe. As Gimbutas' beliefs evolved, she put increasing emphasis on the patriarchal, patrilinear nature of the invading culture, sharply contrasting it with the supposedly egalitarian, if not matrilinear culture of the invaded, to a point of formulating essentially feminist archaeology. A modified form of this theory by JP Mallory, dating the migrations earlier to around 3500 BC and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, remains the most widely held view of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat.

The Anatolian hypothesis is that the Indo-European languages spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BCE with the advance of farming (wave of advance). The leading propagator of the theory is Colin Renfrew. The culture of the Indo-Europeans as inferred by linguistic reconstruction contradicts this theory, since early Neolithic cultures had neither the horse, nor the wheel, nor metal, terms for all of which are securely reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European. Renfrew dismisses this argument, comparing such reconstructions to a theory that the presence of the word "café" in all modern Romance languages implies that the Ancient Romans had cafés too - the linguistic counter-argument to this being that whereas there can be no clear Proto-Romance reconstruction of the word "café" according to historical linguistic methodology, words such as "wheel" in the Indo-European languages clearly point to an archaic form of the protolanguage. Another one of arguments against Renfrew is the fact that ancient Anatolia is known to have been inhabited by non-Indo-European people, namely the Hattians, Khalib/Karub, and Khaldi/Kardi; though this does not preclude the possibility that the earliest Indo-European speakers may have been there too.

Using stochastic models of word evolution to study the presence or absence of different words across Indo-European languages, Gray and Atkinson suggest that the origin of Indo-European goes back about 8500 years, the first split being that of Hittite from the rest, supporting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis. They attempt to avoid one problem associated with traditional glottochronology – that of linguistic borrowing. However, they inherit the main problems of glottochronology, including the lack of proof that languages have a steady rate of lexical replacement. Their calculations rely entirely on Swadesh lists, and while the results are quite robust for well attested branches, their crucial calculation of the age of Hittite rests on a 200–word Swadesh list of one single language.[13] A more recent paper analyzing 24 mostly ancient languages, including three Anatolian languages, produced the same time estimates and early Anatolian split.[14] These claims are still controversial, however, and most traditional linguists consider these methods too inaccurate to prove the Anatolian hypothesis.[15]

The Armenian hypothesis is based on the Glottalic theory and suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 4th millennium BCE in the Armenian Highland. It is an Indo-Hittite model and does not include the Anatolian languages in its scenario. The phonological peculiarities of PIE proposed in the Glottalic theory would be best preserved in the Armenian language and the Germanic languages, the former assuming the role of the dialect which remained in situ, implied to be particularly archaic in spite of its late attestation. Proto-Greek would be practically equivalent to Mycenean Greek and date to the 17th century BCE, closely associating Greek migration to Greece with the Indo-Aryan migration to India at about the same time (viz., Indo-European expansion at the transition to the Late Bronze Age, including the possibility of Indo-European Kassites). The Armenian hypothesis argues for the latest possible date of Proto-Indo-European (sans Anatolian), a full millennium later than the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis. In this, it figures as an opposite to the Anatolian hypothesis, in spite of the geographical proximity of the respective Urheimaten suggested, diverging from the time-frame suggested there by a full three millennia.[16]

In the 20th century, Marija Gimbutas created the Kurgan hypothesis. The name is taken from the kurgans (burial mounds) of the Eurasian steppes. The hypothesis is that the Indo-Europeans were a nomadic tribe of the Pontic-Caspian steppe (now Eastern Ukraine and Southern Russia) and expanded in several waves during the 3rd millennium BC. Their expansion coincided with the taming of the horse. Leaving archaeological signs of their presence (see battle-axe people), they subjugated the peaceful European Neolithic farmers of Gimbutas' Old Europe. As Gimbutas' beliefs evolved, she put increasing emphasis on the patriarchal, patrilinear nature of the invading culture, sharply contrasting it with the supposedly egalitarian, if not matrilinear culture of the invaded, to a point of formulating essentially feminist archaeology. A modified form of this theory by JP Mallory, dating the migrations earlier to around 3500 BC and putting less insistence on their violent or quasi-military nature, remains the most widely held view of the Proto-Indo-European Urheimat.

The Anatolian hypothesis is that the Indo-European languages spread peacefully into Europe from Asia Minor from around 7000 BCE with the advance of farming (wave of advance). The leading propagator of the theory is Colin Renfrew. The culture of the Indo-Europeans as inferred by linguistic reconstruction contradicts this theory, since early Neolithic cultures had neither the horse, nor the wheel, nor metal, terms for all of which are securely reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European. Renfrew dismisses this argument, comparing such reconstructions to a theory that the presence of the word "café" in all modern Romance languages implies that the Ancient Romans had cafés too - the linguistic counter-argument to this being that whereas there can be no clear Proto-Romance reconstruction of the word "café" according to historical linguistic methodology, words such as "wheel" in the Indo-European languages clearly point to an archaic form of the protolanguage. Another one of arguments against Renfrew is the fact that ancient Anatolia is known to have been inhabited by non-Indo-European people, namely the Hattians, Khalib/Karub, and Khaldi/Kardi; though this does not preclude the possibility that the earliest Indo-European speakers may have been there too.

Using stochastic models of word evolution to study the presence or absence of different words across Indo-European languages, Gray and Atkinson suggest that the origin of Indo-European goes back about 8500 years, the first split being that of Hittite from the rest, supporting the Indo-Hittite hypothesis. They attempt to avoid one problem associated with traditional glottochronology – that of linguistic borrowing. However, they inherit the main problems of glottochronology, including the lack of proof that languages have a steady rate of lexical replacement. Their calculations rely entirely on Swadesh lists, and while the results are quite robust for well attested branches, their crucial calculation of the age of Hittite rests on a 200–word Swadesh list of one single language.[13] A more recent paper analyzing 24 mostly ancient languages, including three Anatolian languages, produced the same time estimates and early Anatolian split.[14] These claims are still controversial, however, and most traditional linguists consider these methods too inaccurate to prove the Anatolian hypothesis.[15]

The Armenian hypothesis is based on the Glottalic theory and suggests that the Proto-Indo-European language was spoken during the 4th millennium BCE in the Armenian Highland. It is an Indo-Hittite model and does not include the Anatolian languages in its scenario. The phonological peculiarities of PIE proposed in the Glottalic theory would be best preserved in the Armenian language and the Germanic languages, the former assuming the role of the dialect which remained in situ, implied to be particularly archaic in spite of its late attestation. Proto-Greek would be practically equivalent to Mycenean Greek and date to the 17th century BCE, closely associating Greek migration to Greece with the Indo-Aryan migration to India at about the same time (viz., Indo-European expansion at the transition to the Late Bronze Age, including the possibility of Indo-European Kassites). The Armenian hypothesis argues for the latest possible date of Proto-Indo-European (sans Anatolian), a full millennium later than the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis. In this, it figures as an opposite to the Anatolian hypothesis, in spite of the geographical proximity of the respective Urheimaten suggested, diverging from the time-frame suggested there by a full three millennia.[16]

Genetics

Further information: Genetic history of Europe, Genetic history of South Asia and Genetic history of the Near East

Frequency distribution of R1a1a, also known as R-M17 and R-M198, adapted from Underhill et al. (2009).

The rise of archaeogenetic

evidence which uses genetic analysis to trace migration patterns also

added new elements to the origins puzzle. In terms of genetics, the subcladeR1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) is the most commonly associated with Indo-European speakers. The subclade's parent Y-chromosome DNA haplogroupR1a1 is thought to have originated in either the Eurasian Steppe (north of the Black Sea and Caspian Sea) or the Indus Valley.[17] The mutations that characterize haplogroup R1a occurred ~10,000 years BP. Its defining mutation (M17) occurred about 10,000 to 14,000 years ago. Ornella Semino et al. propose a postglacial (Holocene) spread of the R1a1 haplogroup from north of the Black Sea during the time of the Late Glacial Maximum, which was subsequently magnified by the expansion of the Kurgan culture into Europe and eastward.[18] Data so far collected indicate that there are two widely separated areas of high frequency, one in Eastern Europe, around Poland and the Russian core, and the other in South Asia, around North India.

The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the

subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population

geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of

potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

Out of 10 human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, nine possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C-M130 haplogroup (xC3). mtDNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (two individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b. Furthermore, 90% of the Bronze Age period mtDNA haplogroups were of west Eurasian origin and the study determined that at least 60% of the individuals overall (out of the 26 Bronze and Iron Age human remains' samples of the study that could be tested) had light hair and blue or green eyes.[19]

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian origin (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th centuries BCE, all samples from Kazakhstan belonged to European lineages.[20]

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza argue that Renfrew and Gimbutas reinforce rather than contradict each other. Cavalli-Sforza (2000) states that "It is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey." Piazza & Cavalli-Sforza (2006) state that:

Out of 10 human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, nine possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C-M130 haplogroup (xC3). mtDNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (two individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b. Furthermore, 90% of the Bronze Age period mtDNA haplogroups were of west Eurasian origin and the study determined that at least 60% of the individuals overall (out of the 26 Bronze and Iron Age human remains' samples of the study that could be tested) had light hair and blue or green eyes.[19]

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian origin (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th centuries BCE, all samples from Kazakhstan belonged to European lineages.[20]

Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Alberto Piazza argue that Renfrew and Gimbutas reinforce rather than contradict each other. Cavalli-Sforza (2000) states that "It is clear that, genetically speaking, peoples of the Kurgan steppe descended at least in part from people of the Middle Eastern Neolithic who immigrated there from Turkey." Piazza & Cavalli-Sforza (2006) state that:

if the expansions began at 9,500 years ago from Anatolia and at 6,000 years ago from the Yamnaya culture region, then a 3,500-year period elapsed during their migration to the Volga-Don region from Anatolia, probably through the Balkans. There a completely new, mostly pastoral culture developed under the stimulus of an environment unfavourable to standard agriculture, but offering new attractive possibilities. Our hypothesis is, therefore, that Indo-European languages derived from a secondary expansion from the Yamnaya culture region after the Neolithic farmers, possibly coming from Anatolia and settled there, developing pastoral nomadism.Spencer Wells suggests in a (2001) study that the origin, distribution and age of the R1a1haplotype points to an ancient migration, possibly corresponding to the spread by the Kurgan people in their expansion across the Eurasian steppe around 3000 BCE. About his old teacher Cavalli-Sforza's proposal, Wells (2002) states that "there is nothing to contradict this model, although the genetic patterns do not provide clear support either", and instead argues that the evidence is much stronger for Gimbutas' model:

While we see substantial genetic and archaeological evidence for an Indo-European migration originating in the southern Russian steppes, there is little evidence for a similarly massive Indo-European migration from the Middle East to Europe. One possibility is that, as a much earlier migration (8,000 years old, as opposed to 4,000), the genetic signals carried by Indo-European-speaking farmers may simply have dispersed over the years. There is clearly some genetic evidence for migration from the Middle East, as Cavalli-Sforza and his colleagues showed, but the signal is not strong enough for us to trace the distribution of Neolithic languages throughout the entirety of Indo-European-speaking Europe.

Kurgan hypothesis

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Map of Indo-European migrations

from ca. 4000 to 1000 BC according to the Kurgan model. The Anatolian

migration (indicated with a dotted arrow) could have taken place either

across the Caucasus or across the Balkans. The magenta area corresponds

to the assumed Urheimat (Samara culture, Sredny Stog culture).

The red area corresponds to the area that may have been settled by

Indo-European-speaking peoples up to ca. 2500 BC, and the orange area by

1000 BC.

Indo-European isoglosses, including the centum and satem languages (blue and red, respectively), augment, PIE *-tt- > -ss-, *-tt- > -st-, and m-endings.

Part of a series on

The Kurgan hypothesis (also theory or model) is the dominant theory of several scenarios for the Indo-European origins.[note 1] It postulates that the people of an archaeological "Kurgan culture" in the Pontic steppe were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. The term is derived from kurgan (курган), a Turkic loanword in Russian for a tumulus or burial mound.

The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various cultures, including the Yamna, or Pit Grave, culture and its predecessors. David Anthony instead used the core Yamna Culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.

Marija Gimbutas defined the "Kurgan culture" as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper/Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BC). The bearers of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[3]

The Kurgan hypothesis (also theory or model) is the dominant theory of several scenarios for the Indo-European origins.[note 1] It postulates that the people of an archaeological "Kurgan culture" in the Pontic steppe were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language. The term is derived from kurgan (курган), a Turkic loanword in Russian for a tumulus or burial mound.

The Kurgan hypothesis was first formulated in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various cultures, including the Yamna, or Pit Grave, culture and its predecessors. David Anthony instead used the core Yamna Culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.

Marija Gimbutas defined the "Kurgan culture" as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper/Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BC). The bearers of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC expanded throughout the Pontic-Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[3]

Contents

[hide]Overview

When it was first proposed in 1956, in The Prehistory of Eastern Europe, Part 1, Marija Gimbutas's contribution to the search for Indo-European origins was a pioneering interdisciplinary synthesis of archaeology and linguistics. The Kurgan model of Indo-European origins identifies the Pontic-Caspian steppe as the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) Urheimat,

and a variety of late PIE dialects are assumed to have been spoken

across the region. According to this model, the Kurgan culture gradually

expanded until it encompassed the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe, Kurgan IV being identified with the Pit Grave culture of around 3000 BC.

While arguments for the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as steppe nomads from the Pontic-Caspian region had already been made in the 19th century by Theodor Benfey and Otto Schrader,[4] the idea had never gained traction prior to Gimbutas, with most scholars favouring a Northern European origin instead, linking the Proto-Indo-Europeans to the Corded Ware culture. Gimbutas, who acknowledges Schrader as a precursor,[5] was able to marshal a wealth of archaeological evidence from the territory of the Soviet Union (and other then-communist countries) not readily available to scholars from western countries,[6] enabling her to achieve a fuller picture of prehistoric Europe.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire Pit Grave region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots.[note 2] The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.[note 2]

Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of Proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

While arguments for the identification of the Proto-Indo-Europeans as steppe nomads from the Pontic-Caspian region had already been made in the 19th century by Theodor Benfey and Otto Schrader,[4] the idea had never gained traction prior to Gimbutas, with most scholars favouring a Northern European origin instead, linking the Proto-Indo-Europeans to the Corded Ware culture. Gimbutas, who acknowledges Schrader as a precursor,[5] was able to marshal a wealth of archaeological evidence from the territory of the Soviet Union (and other then-communist countries) not readily available to scholars from western countries,[6] enabling her to achieve a fuller picture of prehistoric Europe.

The mobility of the Kurgan culture facilitated its expansion over the entire Pit Grave region, and is attributed to the domestication of the horse and later the use of early chariots.[note 2] The first strong archaeological evidence for the domestication of the horse comes from the Sredny Stog culture north of the Azov Sea in Ukraine, and would correspond to an early PIE or pre-PIE nucleus of the 5th millennium BC.[note 2]

Subsequent expansion beyond the steppes led to hybrid, or in Gimbutas's terms "kurganized" cultures, such as the Globular Amphora culture to the west. From these kurganized cultures came the immigration of Proto-Greeks to the Balkans and the nomadic Indo-Iranian cultures to the east around 2500 BC.

Kurgan culture

Cultural horizon

Gimbutas defined and introduced the term "Kurgan culture" in 1956

with the intention to introduce a "broader term" that would combine Sredny Stog II, Pit-Grave and Corded ware horizons (spanning the 4th to 3rd millennia in much of Eastern and Northern Europe).[note 3]

The model of a "Kurgan culture" postulates cultural similarity between

the various cultures of the Copper Age to Early Bronze Age (5th to 3rd

millennia BC) Pontic-Caspian steppe to justify the identification as a

single archaeological culture or cultural horizon. The eponymous construction of kurgans

is only one among several factors. As always in the grouping of

archaeological cultures, the dividing line between one culture and the

next cannot be drawn with any accuracy and will be open to debate.

Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the "Kurgan Culture":

Cultures that Gimbutas considered as part of the "Kurgan Culture":

- Bug-Dniester (6th millennium)

- Samara (5th millennium)

- Kvalynsk (5th millennium)

- Sredny Stog (mid-5th to mid-4th millennia)

- Dnieper-Donets (5th to 4th millennia)

- Usatovo culture (late 4th millennium)

- Maikop-Dereivka (mid-4th to mid-3rd millennia)

- Yamna (Pit Grave): This is itself a varied cultural horizon, spanning the entire Pontic-Caspian steppe from the mid-4th to the 3rd millennium.

Yamna culture

David Anthony considers the term "Kurgan Culture" so lacking in

precision as to be useless, instead using the core Yamna Culture and its

relationship with other cultures as a point of reference.[7] He points out that

The Kurgan culture was so broadly defined that almost any culture with burial mounds, or even (like the Baden culture) without them could be included.[7]He does not include the Maikop culture among those that he considers to be IE-speaking, presuming instead that they spoke a Caucasian language.[8]

Stages of culture and expansion

Gimbutas' original suggestion identifies four successive stages of the Kurgan culture:

- Kurgan I, Dnieper/Volga region, earlier half of the 4th millennium BC. Apparently evolving from cultures of the Volga basin, subgroups include the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures.

- Kurgan II–III, latter half of the 4th millennium BC. Includes the Sredny Stog culture and the Maykop culture of the northern Caucasus. Stone circles, anthropomorphic stone stelae of deities.

- Kurgan IV or Pit Grave culture, first half of the 3rd millennium BC, encompassing the entire steppe region from the Ural to Romania.

There were three successive proposed "waves" of expansion:

- Wave 1, predating Kurgan I, expansion from the lower Volga to the Dnieper, leading to coexistence of Kurgan I and the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. Repercussions of the migrations extend as far as the Balkans and along the Danube to the Vinča culture in Serbia and Lengyel culture in Hungary.

- Wave 2, mid 4th millennium BC, originating in the Maykop culture and resulting in advances of "kurganized" hybrid cultures into northern Europe around 3000 BC (Globular Amphora culture, Baden culture, and ultimately Corded Ware culture). According to Gimbutas this corresponds to the first intrusion of Indo-European languages into western and northern Europe.

- Wave 3, 3000–2800 BC, expansion of the Pit Grave culture beyond the steppes, with the appearance of the characteristic pit graves as far as the areas of modern Romania, Bulgaria, eastern Hungary and Georgia, coincident with the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and Trialeti culture in Georgia (c.2750 BC).

Timeline

- 4500–4000: Early PIE. Sredny Stog, Dnieper-Donets and Samara cultures, domestication of the horse (Wave 1).

- 4000–3500: The Pit Grave culture (a.k.a. Yamna culture), the prototypical kurgan builders, emerges in the steppe, and the Maykop culture in the northern Caucasus. Indo-Hittite models postulate the separation of Proto-Anatolian before this time.

- 3500–3000: Middle PIE. The Pit Grave culture is at its peak, representing the classical reconstructed Proto-Indo-European society with stone idols, predominantly practicing animal husbandry in permanent settlements protected by hillforts, subsisting on agriculture, and fishing along rivers. Contact of the Pit Grave culture with late Neolithic Europe cultures results in the "kurganized" Globular Amphora and Baden cultures (Wave 2). The Maykop culture shows the earliest evidence of the beginning Bronze Age, and Bronze weapons and artifacts are introduced to Pit Grave territory. Probable early Satemization.

- 3000–2500: Late PIE. The Pit Grave culture extends over the entire Pontic steppe (Wave 3). The Corded Ware culture extends from the Rhine to the Volga, corresponding to the latest phase of Indo-European unity, the vast "kurganized" area disintegrating into various independent languages and cultures, still in loose contact enabling the spread of technology and early loans between the groups, except for the Anatolian and Tocharian branches, which are already isolated from these processes. The Centum-Satem break is probably complete, but the phonetic trends of Satemization remain active.

Genetics

Main article: Archaeogenetics of Europe

The term "kurganized" used by Gimbutas implied that the culture could

have been spread by no more than small bands who imposed themselves on

local people as an elite. This idea of the IE language and its

daughter-languages diffusing east and west without mass movement has

proved popular with archaeologists. However, geneticists have opened up

the possibility that these languages spread through population

movements.

Geneticists have noted the correlation of a specific haplogroupR1a1a defined by the M17 (SNP marker) of the Y chromosome

and speakers of Indo-European languages in Europe and Asia. The

connection between Y-DNA R-M17 and the spread of Indo-European languages

was first proposed by Zerjal and colleagues in 1999.[9] and subsequently supported by other authors.[10]Spencer Wells deduced from this correlation that R1a1a arose on the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[11]

Subsequent studies on ancient DNA tested the hypothesis. Skeletons from the Andronovo culture horizon (strongly supposed to be culturally Indo-Iranian) of south Siberia were tested for DNA. Of the 10 males, 9 carried Y-DNA R1a1a (M17). Fairly close matches were found between the ancient DNA STR haplotypes and those in living persons in both eastern Europe and Siberia.[12] Mummies in the Tarim Basin also proved to carry R1a1a and were presumed to be ancestors of Tocharian speakers.[13]

A study published in 2012 states that "R1a1a7-M458 was absent in Afghanistan, suggesting that R1a1a-M17 does not support, as previously thought, expansions from the Pontic Steppe, bringing the Indo-European languages to Central Asia and India."[14] However, this study does not in any way conflict with the hypothesis of expansions from the Pontic Steppe, since the study does not take into account the early wave of the Indo-European speaking people. Even today the R1a1a7-M458 are very rare, almost absent, in the area of the proposed Indo-European origins between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea; the R1a1a7-M458 marker first started in Poland 10,000 years ago (KYA), and arrived in the western fringes of the Pontic steppe 5,000 years ago and the eastern fringes only 2,500 years ago, while the first Indo-European wave (4500–4000 BC Early PIE) began up to 4,000 years before this.

The DNA testing of remains from kurgans also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying an origin close to Europe for this population.[15]

Several 4,600 year-old human remains at a Corded Ware site in Eulau, Germany, were also found to belong to haplogroup R1a1a.[16]

Subsequent studies on ancient DNA tested the hypothesis. Skeletons from the Andronovo culture horizon (strongly supposed to be culturally Indo-Iranian) of south Siberia were tested for DNA. Of the 10 males, 9 carried Y-DNA R1a1a (M17). Fairly close matches were found between the ancient DNA STR haplotypes and those in living persons in both eastern Europe and Siberia.[12] Mummies in the Tarim Basin also proved to carry R1a1a and were presumed to be ancestors of Tocharian speakers.[13]

A study published in 2012 states that "R1a1a7-M458 was absent in Afghanistan, suggesting that R1a1a-M17 does not support, as previously thought, expansions from the Pontic Steppe, bringing the Indo-European languages to Central Asia and India."[14] However, this study does not in any way conflict with the hypothesis of expansions from the Pontic Steppe, since the study does not take into account the early wave of the Indo-European speaking people. Even today the R1a1a7-M458 are very rare, almost absent, in the area of the proposed Indo-European origins between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea; the R1a1a7-M458 marker first started in Poland 10,000 years ago (KYA), and arrived in the western fringes of the Pontic steppe 5,000 years ago and the eastern fringes only 2,500 years ago, while the first Indo-European wave (4500–4000 BC Early PIE) began up to 4,000 years before this.

The DNA testing of remains from kurgans also indicated a high prevalence of people with characteristics such as blue (or green) eyes, fair skin and light hair, implying an origin close to Europe for this population.[15]

Several 4,600 year-old human remains at a Corded Ware site in Eulau, Germany, were also found to belong to haplogroup R1a1a.[16]

Further expansion during the Bronze Age

Main article: Indo-European migrations

The Kurgan hypothesis describes the initial spread of Proto-Indo-European during the 5th and 4th millennia BC.[17] The question of further Indo-Europeanization of Central and Western Europe, Central Asia and Northern India during the Bronze Age is beyond its scope, far more uncertain than the events of the Copper Age, and subject to some controversy.

Anatolia

The Anatolian languages are a family of extinct Indo-European languages that were spoken in Asia Minor (ancient Anatolia), the best attested of them being the Hittite language. The Maykop culture (also spelled Maikop), ca. 3700 BC—3000 BC,[18] was a major Bronze Age archaeological culture in the Western Caucasus region of Southern Russia. The Hittites were an ancient Anatolian people who established an empire at Hattusa in north-central Anatolia around 1600 BC. This empire reached its height during the mid-14th century BC under Suppiluliuma I, when it encompassed an area that included most of Asia Minor as well as parts of the northern Levant and Upper Mesopotamia. After c. 1180 BC, the empire came to an end during the Bronze Age collapse, splintering into several independent "Neo-Hittite" city-states, some of which survived until the 8th century BC.

Europe

Further information: Corded Ware and Bronze Age Europe

The European Funnelbeaker and Corded Ware

cultures have been described as showing intrusive elements linked to

Indo-Europeanization, but recent archaeological studies have described

them in terms of local continuity, which has led some archaeologists to

declare the Kurgan hypothesis "obsolete".[19]

However, it is generally held unrealistic to believe that a

proto-historic people can be assigned to any particular group on basis

of archaeological material alone.[20]

The Corded Ware culture has always been important in locating Indo-European origins. The German archaeologist Alexander Häusler was an important proponent of archeologists that searched for homeland evidence here. He sharply criticised Gimbutas' concept of "a" Kurgan culture that mixes several distinct cultures like the pit-grave culture. Häusler's criticism mostly stemmed from a distinctive lack of archeological evidence until 1950 from what was then the East Bloc, from which time on plenty of evidence for Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis was discovered for decades.[21] He was unable to link Corded Ware to the Indo-Europeans of the Balkans, Greece or Anatolia, or to the Indo-Europeans in Asia. Nevertheless, establishing the correct relationship between the Corded Ware and Pontic-Caspian regions is still considered essential to solving the entire homeland problem.[22]

The Corded Ware culture has always been important in locating Indo-European origins. The German archaeologist Alexander Häusler was an important proponent of archeologists that searched for homeland evidence here. He sharply criticised Gimbutas' concept of "a" Kurgan culture that mixes several distinct cultures like the pit-grave culture. Häusler's criticism mostly stemmed from a distinctive lack of archeological evidence until 1950 from what was then the East Bloc, from which time on plenty of evidence for Gimbutas's Kurgan hypothesis was discovered for decades.[21] He was unable to link Corded Ware to the Indo-Europeans of the Balkans, Greece or Anatolia, or to the Indo-Europeans in Asia. Nevertheless, establishing the correct relationship between the Corded Ware and Pontic-Caspian regions is still considered essential to solving the entire homeland problem.[22]

Central Asia

From the Pontic Steppe Indo-European people moved east, where they founded the Sintashta culture and the Andronovo culture. The Sintashta culture, also known as the Sintashta-Petrovka culture[23] or Sintashta-Arkaim culture,[24] is a Bronze Agearchaeological culture of the northern Eurasian steppe on the borders of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, dated to the period 2100–1800 BCE.[25] The Andronovo culture is a collection of similar local Bronze AgeIndo-Iranian cultures that flourished ca. 1800–1400 BCE in western Siberia and the west Asiatic steppe. It is probably better termed an archaeological complex or archaeological horizon. The name derives from the village of Andronovo (

55°53′N 55°42′E / 55.883°N 55.700°E), where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. From these cultures further migrations went further east, to found the Afanasevo culture, and the Tocharian languages formerly spoken by Tocharian peoples in oases on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (now part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China). The Indo-Iranian branch went south, forming the Iranian people and the Indo-Aryan migration into India. Closely related to the Indo-Aryans were the Mitanni, who founded a kingdom in the Middle East.

55°53′N 55°42′E / 55.883°N 55.700°E), where in 1914, several graves were discovered, with skeletons in crouched positions, buried with richly decorated pottery. From these cultures further migrations went further east, to found the Afanasevo culture, and the Tocharian languages formerly spoken by Tocharian peoples in oases on the northern edge of the Tarim Basin (now part of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region of China). The Indo-Iranian branch went south, forming the Iranian people and the Indo-Aryan migration into India. Closely related to the Indo-Aryans were the Mitanni, who founded a kingdom in the Middle East.

Revisions

Invasionist vs. diffusionist scenarios

Gimbutas

believed that the expansions of the Kurgan culture were a series of

essentially hostile, military incursions where a new warrior culture

imposed itself on the peaceful, matriarchal cultures of "Old Europe", replacing it with a patriarchalwarrior society,[26] a process visible in the appearance of fortified settlements and hillforts and the graves of warrior-chieftains:

- "The process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation. It must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups."[27]

In her later life, Gimbutas increasingly emphasized the violent nature of this transition from the Mediterranean cult of the Mother Goddess to a patriarchal society and the worship of the warlike Thunderer (Zeus, Dyaus), to a point of essentially formulating feminist archaeology.

Many scholars who accept the general scenario of Indo-European

migrations proposed, maintain that the transition was likely much more

gradual and peaceful than suggested by Gimbutas. The migrations were

certainly not a sudden, concerted military operation, but the expansion

of disconnected tribes and cultures, spanning many generations. To what

degree the indigenous cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently

displaced remains a matter of controversy among supporters of the Kurgan

hypothesis.

JP Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognizes valid criticism of Gimbutas' radical scenario of military invasion:

JP Mallory (in 1989) accepted the Kurgan hypothesis as the de facto standard theory of Indo-European origins, but he recognizes valid criticism of Gimbutas' radical scenario of military invasion:

One might at first imagine that the economy of argument involved with the Kurgan solution should oblige us to accept it outright. But critics do exist and their objections can be summarized quite simply – almost all of the arguments for invasion and cultural transformations are far better explained without reference to Kurgan expansions, and most of the evidence so far presented is either totally contradicted by other evidence or is the result of gross misinterpretation of the cultural history of Eastern, Central, and Northern Europe."[28]

Kortlandt's proposal

Frederik Kortlandt in 1989 proposed a revision of the Kurgan model.[29]

He states the main objection which can be raised against Gimbutas'

scheme (e.g., 1985: 198) is that it starts from the archaeological

evidence and looks for a linguistic interpretation. Starting from the

linguistic evidence and trying to fit the pieces into a coherent whole,

he arrives at the following picture: The territory of the Sredny Stog culture

in the eastern Ukraine he calls the most convincing candidate for the

original Indo-European homeland. The Indo-Europeans who remained after