Also, it would look really cool.

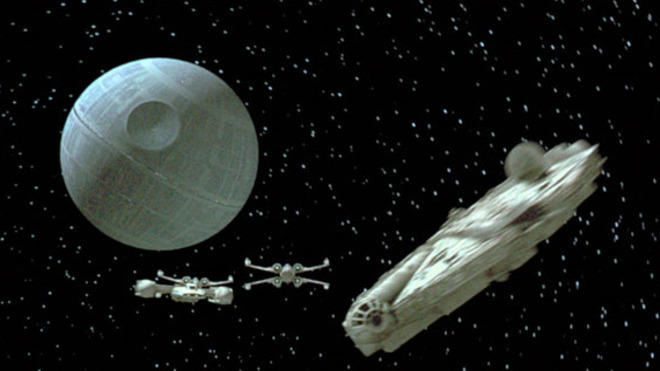

More than 34,000 people had signed the petition, claiming that the project would spur job creation and strengthen defense. They wanted the government to begin construction by 2016. The Obama administration jokingly responded that the cost — estimated to be $850 quadrillion — was far too high, and that the Obama administration "does not support blowing up planets."

The origin of the idea appears to be a rather amusing satirical post by the Glenn Beck-endorsed finance blog Zero Hedge from January 2012. Zero Hedge calculated that at current steel prices, the steel alone would cost $852 quadrillion, or 13,000 times the current level of global economic activity per year. And while there exists enough iron in the Earth’s crust to build two billion Death Stars, the steel itself would take 833,315 years to produce at current rates of production.

The point of all this was to make an attack on the concept of government being able to stimulate the economy by employing idle economic resources. While it may be possible to boost economic activity by any amount through government spending, there is no guarantee whatsoever that such government spending will do anything productive. Zero Hedge portrays Death Star-like projects as misallocations of capital, resources and labor since nobody in the market wants or needs them. This is a superficially impressive point. After all, didn’t the economies of communist countries like the Soviet Union collapse due to the failure of central economic planning, where the government and not the market decides how to allocate resources?

Yet the more I thought about it, the more I started to think that actually, building the Death Star would be a great idea. It would have massively beneficial economic effects for employment, output, science, technology and so forth. Any civilization that can build such a thing is both immensely powerful, and immensely skilled. More importantly, I think it is possible in the very, very long run for a government to build the Death Star or something similar of a smaller scale without misallocating any capital, labour, technology or resources whatsoever.

Let's start with Zero Hedge's presumptions. It’s cost estimate, for instance, is actually quite minimal, since it only includes the cost of the steel, and not the cost of getting the steel into space, constructing the steel into a Death Star, the development of laser cannon technology, a propulsion system, the feeding and housing of a large permanent crew (including oxygen and water recycling facilities), hydroponics and artificial food production technologies, a transport system to get people and things between the Earth and the Death Star, etc. Nor does it take into account the cost of the labor in employing scientists and technologists to develop and prototype the technologies, hiring engineers to deploy the technology, and producing components and parts. So I think the cost would far exceed even what Zero Hedge projects, possibly many times over.

SEE ALSO: 7 grammar rules you really should pay attention to

So why would I think that committing to spend vastly more than global GDP on a single project that nobody in the market is demanding is a good idea? Well, on a potentially infinite timeline, such a huge figure becomes more and more affordable as we go further and further into the future. While a Death Star may appear to be absurdly far beyond our present economic capabilities, the same was once true of things that are now within our capabilities like fighter jets or nuclear reactors. What made such things possible was time and scientific, technological and organizational development.

To build a Death Star, we would need to begin work on challenges far more modest and far closer to our present capabilities — sending a human to Mars, setting up a permanent base on the moon, setting up a permanent base on Mars, and developing technologies for those purposes. On the technology side, we would at least need multi-use lifters, a space elevator, improved solar energy collection and storage, improved nuclear batteries, improved 3D printing technologies, higher energy particle accelerators, space mining technologies, robots, machine learning, computing, life support systems and things as mundane as increased science and science education spending.

In order to avoid misallocating capital like the Soviet Union and other command economies, government’s capacity for extra stimulus is only the resources that the market has let sit idle. Idle resources can be estimated by the output gap — the difference between measured economic output, and the long term trend — which currently sits at around $856 billion, and by unemployment which currently sits at 7.2 percent. Both of these figures are very high by historical standards, suggesting that the economy is somewhat depressed, and that government still has significant capacity to engage in stimulus, especially in the current ultra-low interest rate environment. By those measures, building the Death Star today is not currently a suitable project, because its cost far exceeds the amount of idle resources in the economy.

But the United States could fund more modest missions to get us closer to that long-term goal. For instance, it could allocate money for a manned mission to Mars ($6 billion), build a new high energy particle accelerator ($12 billion), give out 10,000 million dollar research grants ($10 billion), build a base on the Moon ($35 billion), and invest $20 billion more in science education for, all for less than 10 percent of the current output gap. Better still, NASA and space-related spending historically has a relatively high multiplier of at least $2 (and possibly as much as $14 for certain projects, as well as a multiplier of 2.8 additional jobs for every job directly created) of extra economic activity generated per dollar spent. Given that space-spending yields new technologies like global positioning systems, satellite broadcasting, 3D printers, touch screens, and memory foam that lead to new products, these benefits are unsurprising. These projects woudl also help develop the private space industry, since existing private enterprise is piggybacking on technology and progress made 40 or 50 years ago in state-funded programs like the Apollo program.

If we started with these modest projects, the next time the economy has a bout of idle resources and unemployment, we could commence a new series of such large-scale projects. Eventually, projects on the scale of the Death Star may become not only economically viable but a valuable contribution to humanity.

Our civilization sits in dangerous territory right now. There are over seven billion of us, yet we are all concentrated on one ecosystem — the Earth, with one tiny totally-dependent off-planet colony, the International Space Station, which houses less than 10 people at a time. A single mass viral pandemic, asteroid strike or other cataclysm could completely wipe our species out. With humanity spread throughout the solar system — and preferably, the galaxy and the universe — our species is far less fragile to random extinction events. If we had access to the technology necessary to build a Death Star, we could easily begin to colonize space. And the Death Star itself — a giant space weapon — would be a safeguard against a particular kind of cataclysmic risk, that of hostile alien attack.

In conclusion, the Death Star today is far beyond current human capacities, and far beyond the capacity of the idle capital, labor and resources that any government has of deploying. This I must concede. But, as a super-long-term goal, the capacity to build such things is what our civilization ought to aspire to. And there are many projects that are within our capabilities that will take us closer to it.

No comments:

Post a Comment