From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Neolithic clay amulet (retouched), part of the Tărtăria tablets set, dated to 5500-5300 BC and associated with the Turdaş-Vinča culture. The Vinča symbols on it predate the proto-Sumerian pictographic script. Discovered in 1961 at Tărtăria by the archaeologist Nicolae Vlassa.

In 1961, members of a team led by Nicolae Vlassa, an archaeologist at the National Museum of Transylvanian History, Cluj-Napoca in charge of the site excavations, unearthed three inscribed but unbaked clay tablets, together with 26 clay and stone figurines and a shell bracelet, accompanied by the burnt, broken, and disarticulated bones of an adult male.[3][4]

Two of the tablets are rectangular and the third is round.[5] They are all small, the round one being only 6 cm (2½ in) across, and two — one round and one rectangular — have holes drilled through them.

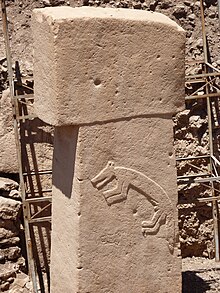

All three have symbols inscribed only on one face.[5] The unpierced rectangular tablet depicts a horned animal, an unclear figure, and a vegetal motif, a branch or tree. The others have a variety of mainly abstract symbols. The purpose of the burial is unclear, but it has been suggested that the body was, if not that of a shaman or spirit-medium, that of a local most respected wise person.[3]

Contents

Earlier discoveries

Similar motifs have been found on pots excavated at Gradeshnitsa in Bulgaria, Vinča in Serbia and a number of other locations in the southern Balkans.[citation needed]The Vinča symbols have been known since the late 19th century excavation at the Neolithic site of Turdaş in Transylvania Romania, by Zsófia Torma.[6]

Dating

Workers at the conservation department of the Cluj museum baked the originally unbaked clay tablets to preserve them. This made direct dating of the tablets themselves through carbon 14 method impossible.[7]The tablets are generally believed to have belonged to the Vinča-Turdaș culture, which at the time was believed by Serbian and Romanian archaeologists to have originated around 2700 BC. Vlassa interpreted the Tărtăria tablets as a hunting scene and the other two with signs as a kind of primitive writing similar to the early pictograms of the Sumerians. The discovery caused great interest in the archeological world as it predated the first Minoan writing, the oldest known writing in Europe.

However, subsequent radiocarbon dating on the Tărtăria finds pushed the date of the tablets (and therefore of the whole Vinča culture) much further back, to as long ago as 5500 BC, the time of the early Eridu phase of the Sumerian civilization in Mesopotamia.[8] Still, this is disputed in the light of apparently contradictory stratigraphic evidence.[9]

If the symbols are indeed a form of writing, then writing in the Danubian culture would far predate the earliest Sumerian cuneiform script or Egyptian hieroglyphs. They would thus be the world's earliest known form of writing. This claim remains controversial.

Interpretation

The meaning (if any) of the symbols is unknown, and their nature has been the subject of much debate. Scholars who conclude that the inscribed symbols are writing base their assessment on a few assumptions which are not universally endorsed. First, the existence of similar signs on other artifacts of the Danube civilization suggest that there was an inventory of standard shapes of which scribes made use of. Second, the symbols make a high degree of standardization and a rectilinear shape comparable to what archaic writing systems manifest. Third, that the information communicated by each character was a specific one with an unequivocal meaning. Finally, that the inscriptions are sequenced in rows, whether horizontal, vertical or circular. If they do comprise a script, it is not known what kind of writing system they represent. Some archaeologists who support the idea that they do represent writing, notably Marija Gimbutas, have proposed that they are fragments of a system dubbed the Old European Script.Others consider the pictograms to be accompanied by random scribbles. Some have suggested that the symbols may have been used as marks of ownership or as the focus of religious rituals. An alternative suggestion is that they may have been merely uncomprehending imitations of more advanced cultures, although this explanation is made rather unlikely by the great antiquity of the tablets—there were no known literate cultures at the time from which the symbols could have been adopted.[8] Colin Renfrew argues that the apparent similarities with Sumerian symbols are deceptive: "To me, the comparison made between the signs on the Tărtăria tablets and those of proto-literate Sumeria carry very little weight. They are all simple pictographs, and a sign for a goat in one culture is bound to look much like the sign for a goat in another. To call these Balkan signs 'writing' is perhaps to imply that they had an independent significance of their own communicable to another person without oral contact. This I doubt."[10]

Another problem is that there are no independent indications of literacy existing in the Balkans at this period. Sarunas Milisauskas comments that "it is extremely difficult to demonstrate archaeologically whether a corpus of symbols constitutes a writing system" and notes that the first known writing systems were all developed by early states to facilitate record-keeping in complex organised societies in the Middle East and Mediterranean. There is no evidence of organised states in the European Neolithic, so it is likely that they would not have needed the administrative systems facilitated by writing. David Anthony notes that Chinese characters were first used for ritual and commemorative purposes associated with the 'sacred power' of kings; it is possible that a similar usage accounts for the Tărtăria symbols.[11]

Possible relationships to the area

This group of artefacts, including the tablets, have some relation with the culture developed in the Black sea - Aegean area. Similar are found in Bulgaria the Gradeshnitsa tablets, Dispilio Tablet from southwest Macedonia etc. The material and the style used for the Tartaria artefacts shows some similarities to the ones used in the Cyclades area, as two of the statuettes are made of alabaster.[citation needed]Gradeshnitsa tablets

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Gradeshnitsa tablets(Bulgarian: Плочката от Градешница) or plaques are clay artefacts with incised marks, considered by some, along with the Tărtăria tablets, examples of late neolithic proto-writing known as the Vinča signs.[citation needed] Steven Fischer has written that "The current opinion is that these earliest Balkan symbols appear to comprise a decorative or emblematic inventory with no immediate relation to articulate speech.” That is, they are neither logographs (whole-word signs depicting one object to be spoken aloud) nor phonographs (signs holding a purely phonetic or sound value)."[1] They were unearthed in 1969 in north-western Bulgaria (Gradeshnitsa village, Vratsa Province). The tablets are dated to the 5th millennium BC and are currently preserved in the Vratsa Archeological Museum of Bulgaria.[2] In 2006, these tablets were the subject of attention in Bulgarian media due to claims made by Stephen Guide, a Bulgarian American of the Institute of Transcendent Analysis, Long Beach, California, who claimed he had deciphered the tablets.[3][4][5]

Symbols and proto-writing of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Vinča symbols were also discussed by Marija Gimbutas, who in the 1950s developed her theories that became collectively known as the Old European culture. Gimbutas claimed that these symbols represented an Old European Script that she said was a writing system that predated the Sumerian Cuneiform script. This theory reinforced her claims that the Neolithic civilizations of southeastern Europe were matriarchal, Mother Goddess worshippers, since the symbols were so often found on clay anthropomorphic female fetish figurines that are to be found in archaeological sites throughout the entire region.[1] Her claims have largely been disproven by subsequent research and discoveries,[2] but there are still scholars who support Gimbutas' theories.[3]

Further clouding the issue, there have been several people who have published theories about the Vinča symbols, including one that claims it is the ancient Etruscan alphabet; all of these theories have been disproven by scholars.[2]

The Vinča symbols were found etched or painted on the ubiquitous anthropomorphic female clay statues.[citation needed] These statues have markings on them that appear in roughly the same location (for instance, along the upper arms and shoulders), and are found in various archaeological sites scattered over a wide geographical area.[citation needed]

Beginning in 1875 up to the present, archaeologists have found more than a thousand Neolithic era clay artifacts that have examples of symbols similar to the Vinča symbols scattered widely throughout south-eastern Europe.

These include:

- The Tărtăria Tablets, discovered in 1961 in the village of Tărtăria, Săliştea, Alba County, Romania.

- The Gradeshnitsa Tablets, discovered in 1969 in Gradeshnitsa, Vratsa Province, Bulgaria.

- The Dispilio Tablet, discovered in 1994 in Dispilio, Kastoria regional unit, Greece.

- The Cucuteni-Trypillian pintadera (or barter tokens)

There has been some controversy in the dating of some of these discoveries, especially the Tărtăria Tablets.

-

One of the three Tărtăria tablets, dated 5300 BC

- Looking below, the figure to the left has a symbol made of four lines that are connected to a perpendicular line (or bar) located on the right shoulder. Another female figurine found at a Precucuteni site near Târgu Frumos, in Iaşi County, Romania, has an identical symbol, including the placement of it on the figurine's right shoulder. Târgu Frumos is located a linear 88.5 km. (55 miles) from Ghindaru.

- The figurine on the right has a symbol of three lines connected to a bar and placed on the left shoulder, again identical to other Precucuteni female clay figurines found at sites near the villages of Isaiia, Iaşi County, Romania, and Sabatynivka, Ulianovskyi Raion, Kirovohrad Oblast, Ukraine. Isaiia is located 119 km. (74 miles), and Sabatynivka is 333 km (207 mi) from Ghindaru.

The "Goddess Council" set of figurines

The full exhibit on display at the Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamţ, Romania

Note the four lines on

the shoulder of this

member

Note the four lines on

the shoulder of this

member

Note the three lines

on the shoulder of this

member

Thus it appears that the Vinča or Vinča-Tordos symbols are not restricted to just the region around Belgrade, which is where the Vinča culture existed, but that they spread across most of southeastern Europe, and was used throughout the geographical region of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. This "Goddess Council" example is just one of many that supports the widespread use of these symbols among the Neolithic people of this entire area, and presents very compelling evidence to suggest that these symbols were understood by many individuals who lived in different areas, which lends support to the notion that they were indeed examples of proto-writing, if not a rudimentary writing system.

Abstract symbol on Cucuteni pottery

Economy of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Barter tokens of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture)

| Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (c. 4800 to 3000 BC) |

|---|

Characteristic example of Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery

|

| Topics |

| Related articles |

Main article: Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Throughout most of its existence, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was fairly stable. Near the end it began to change from a gift economy to an early form of trade called reciprocity, and introduced the apparent use of barter tokens, an early form of money.[1]Contents

The Neolithic world

Members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture shared common features with other Neolithic societies, including:- An almost nonexistent social stratification

- Lack of a political elite

- No occupational specialization

- Rudimentary economy, most likely a subsistence or gift economy

- Pastoralists and subsistence farmers

Subsistence economy

Like other Neolithic societies, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture had very little division of labor, other than the ubiquitous dualistic division based upon a person's gender. Although this culture's settlements sometimes grew to become some of the largest on earth at the time (up to 15,000 people), there is no evidence yet discovered of large-scale labor specialization. Their settlements were designed with the houses connecting with one another in long rows that circled around the center of the community. Some settlements did have a central communal building that was designated as a sanctuary or shrine, but there is no indication yet whether or not a separate group or individual would have been supported by the community as a full-time priest or priestess. Almost every home was a self-supporting unit, much as if isolated in the middle of the woods, rather than part of a large settlement. Most homes had their own ceramic kilns, baking ovens, and work centers, indicating that almost all of the work that needed to be done to maintain human existence at the Neolithic standard of living could be done within each household in the community.[2]

Reconstruction of a typical Cucuteni-Trypillian house, in the Cucuteni Museum, Piatra Neamț, Romania. Notice the many varied work stations within the home.

Since every household was almost entirely self-sufficient, there was very little need for trade. Goods and services were exchanged, but a household's survival did not depend on it. In the course of bringing in various resources, it was natural that a given household would reap a windfall of a particular resource, be it a large harvest of apricots, wheat, or a large bison that was brought back by the hunters, etc. When a household found itself with a plentiful supply of a particular resource, it did not necessarily mean that the surplus would be traded in the modern sense of the word, but rather, the surplus would probably be given away to others in the community who could use whatever resource they had on hand, with no thought of reciprocation or direct realized return on the part of the gifters. This is the basis of a gift economy, which has been observed in many hunter-gatherer or subsistence farmer cultures, and that was most likely the same with the Cucuteni-Trypillian society, at least during the early period of the culture.[1]

Primitive trade network

Cucuteni-Trypillian shell artefact, one of the few commodities that were extensively traded in their society

A sample of Miorcani flint from the Cenomanian chalky marl layer of the Moldavian Plateau (approximately 7.5 cm wide)

For more details on this topic, see Technology of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture § World's oldest saltworks.

Other mineral resources that were traded included iron magnetite ore and manganese Jacobsite ore, which came into play later in the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture's development. These minerals were used to create the black pigment that decorated the beautiful ceramic pottery of this culture, and came from two sources: 1) Iacobeni, Suceava County, Romania for the iron magnetite ore, and 2) Nikopol, Dnipropetrovsk Oblast,

Ukraine for the manganese Jacobsite ore, located in the farthest

eastern periphery of the Cucuteni-Trypillian geographical region, along

the Dnieper River.[8]

However, no traces of the manganese Jacobsite ore have been found in

pigments used on artifacts from the western settlements on the opposite

end of the region. This indicates that, although there was a trade

network established, it was still rudimentary.[9]

For more details on this topic, see Technology of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture § Decoration.

Interaction with other societies

The Cucuteni-Trypillian people were exporting Miorcani type flint to the west even from their first appearance. The import of flint from Dobruja indicates an interaction with the Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture and Aldeni-Stoicani cultures to the south. Toward the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture's existence (from roughly 3000 B.C. to 2750 B.C.), copper traded from other societies (mostly from the Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture copper mines of the northeastern Balkan) began to appear throughout the region, and members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture began to acquire skills necessary to use it to create various items. Along with the raw copper ore, finished copper tools, hunting weapons and other artifacts were also brought in from other cultures.[2] In exchange for the imported copper, the Cucuteni-Trypillian traders would export their finely crafted pottery and the high-quality flint that was to be found in their territory, which have been found in archaeological sites in distant lands. However, the Lunca salt, which was ubiquitous throughout the region, was not traded away.[10] The introduction of copper marked the transition from the Neolithic to the Eneolithic, also known as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. This was a transitional period, as it was of a relatively short duration lasting less than 300 years before being replaced by the Bronze Age that was probably introduced by Proto-Indo-European tribes that came into this region from the east. The end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture coincided with the arrival of the Bronze Age. There is much controversy surrounding how the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ended, which is discussed in greater detail in the article Decline and end of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture.Bronze artifacts began to show up in archaeological sites toward the very end of the culture. Beginning as early as 4500 B.C., the Yamna culture, a Proto-Indo-European group from the Pontic steppe north of the Black Sea, began to establish nomadic camps and temporary settlements throughout the region settled by the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.[11] These Proto-Indo-Europeans were nomadic pastoralists, who rode domesticated horses, and ranged over a wide region stretching from the Balkans to Kazakhstan. They had superior technologies in horse domestication, metalworking, and a much more developed trade network compared to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, however the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture had a higher level of technology in regards to agriculture, salt-processing, and ceramics. The Proto-Indo-Europeans acquired technologies to work copper and then bronze much earlier than the Cucuteni-Trypillians, who never quite managed to develop bronze artifacts. The Proto-Indo-Europeans traded their copper and bronze tools and jewelry with the Cucuteni-Trypillians for their elaborately designed and finely crafted pottery.[11]

As these cultures interacted with each other over a period of nearly 2000 years, there is little evidence of open warfare, although there is speculation that the huge Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements grew as large as they did during their later phase of their culture as a result of providing a stronger defense against any potential raiding conducted by nomadic Proto-Indo-European groups that might have been wandering through their neighborhood.[2] Still, remarkably, almost no actual weapons have been found in any Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, neither have there been skeletal remains discovered that would indicate the person had died violently (arrowheads lodged in the bones, crushed skulls, etc.).[12]

Irish-American scholar J. P. Mallory wrote in his 1989 book In search of the Indo-Europeans:

Ethnographic evidence suggests a very fluid boundary between mobile and settled communities, and it is entirely probable that some pastoralists may have settled permanently whilst Tripoleans may have become integrated into the more mobile steppe communities. The resultant archaeological evidence certainly suggests the creation of hybrid communities. By the middle of the fourth millennium B.C. we witness the transformation of Late Tripolye groups into new cultural entities. Probably the most noted is the Usatovo culture, which occupied the territory from the lower Dniester to the mouth of the Danube ... In some aspects the culture retains traditional Tripolye styles of painted wares and figures. But, in addition, there also appears...a considerable series of daggers, along with axes, awls and rings, including rings made from silver, which is a metal we would attribute to the Proto-Indo-Europeans.[11]:p.237The final blow may have come when the favorable agricultural conditions during the Holocene climatic optimum, which lasted from 7000 to 3200 B.C., quite suddenly changed, resulting in the arid Sub-Boreal phase, which created the worst and longest drought in Europe since the end of the last Ice Age. The large Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements, which relied entirely on subsistence agriculture for support, would have faced very nasty Dust Bowl conditions, making it impossible to continue their way of life. It is theorized that the combination of this drought and the existence of neighboring nomadic pastoralist tribes led to the complete collapse of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, and the abandonment of their settlements, as members of the culture left behind the plow to take up the saddle of a nomad, as pastoralists are better equipped to eke out a living in an arid environment. The results were that by 2750 B.C. the Proto-Indo-European culture completely dominated the area.[11] The primitive trade network of the Cucuteni-Trypillian society that had been slowly growing more complex was thus abruptly ended, along with the culture that supported it. Or, rather, it was supplanted by another more advanced trade network as the Proto-Indo-Europeans moved in to take the land, and to bring with them an entirely new society with division of labor, a ruling and religious elite, social stratification, and, in a word, civilization.[2][13]

See also: Chalcolithic Europe

Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Map showing the approximate maximal extent of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (all periods)[1]

| Cucuteni-Trypillian culture (c. 4800 to 3000 BC) |

|---|

Characteristic example of Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery

|

| Topics |

| Related articles |

| Chalcolithic Eneolithic, Aeneolithic or Copper Age |

|---|

| ↑ Stone Age ↑ Neolithic |

| Metallurgy, Wheel, Domestication of the horse, |

| ↓ Bronze Age |

It extends from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions, centered on modern-day Moldova and covering substantial parts of western Ukraine and northeastern Romania, encompassing an area of some 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi), with a diameter of some 500 km (300 mi; roughly from Kiev in the northeast to Brasov in the southwest).[2][3]

The majority of Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements consisted of high-density, small settlements (spaced 3 to 4 kilometers apart), concentrated mainly in the Siret, Prut, and Dniester river valleys.[4] During the Middle Trypillia phase (ca. 4000 to 3500 BC), populations belonging to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which contained as many as 1,600 structures.[5]

One of the most notable aspects of this culture was the periodic destruction of settlements, with each single-habitation site having a roughly 60 to 80 year lifetime.[6] The purpose of burning these settlements is a subject of debate among scholars; some of the settlements were reconstructed several times on top of earlier habitational levels, preserving the shape and the orientation of the older buildings. One particular location, the Poduri site (Romania), revealed thirteen habitation levels that were constructed on top of each other over many years.[6]

Contents

Nomenclature

The culture was initially named after the village of Cucuteni in Iaşi County, Romania. In 1884, Teodor T. Burada, after having seen ceramic fragments in the gravel used to maintain the road from Târgu Frumos to Iași, investigated the quarry in Cucuteni from where the material was mined, where he found fragments of pottery and terracotta figurines. Burada and other scholars from Iaşi, including the poet Nicolae Beldiceanu and archeologists Grigore Butureanu, Dimitrie C. Butculescu and George Diamandy, subsequently began the first excavations at Cucuteni in the spring of 1885.[7] Their findings were published in 1885[8] and 1889,[9] and presented in two international conferences in 1889, both in Paris: at the International Congress of Prehistoric Anthropology and Archaeology by Butureanu[7] and at a meeting of the Société d’Anthropologie de Paris by Diamandi.[10]At the same time, the first Ukrainian sites ascribed to the culture were discovered by Vicenty Khvoika. The year of his discoveries has been variously claimed as 1893,[11] 1896[12] and 1887.[13] Subsequently, Vicenty Khvoika presented his findings at the 11th Congress of Archaeologists in 1897, which is considered the official date of the discovery of the Trypillian Culture in Ukraine.[11][13] In the same year similar artifacts were excavated in the village of Trypillia (Ukrainian: Трипiлля), in Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. As a result, this culture became identified in Ukrainian publications (and later in Soviet Russia), as the 'Tripolie' (or 'Tripolye'), 'Tripolian' or 'Trypillian' culture.

Anthropomorphic Cucuteni-Trypillian clay figure

Geography

Dniester landscape in Ternopil Oblast, Western Ukraine.

The culture thus extended northeast from the Danube River Basin around the Iron Gates gorge to the Black Sea and Dnieper River. It encompassed the central Carpathian Mountains as well as the plains, steppe and forest steppe on either side of the range. Its historical core lay around the middle to upper Dniester River (the Podolian Upland).[3] During the Atlantic and Subboreal climatic periods in which the culture flourished, Europe was at its warmest and moistest since the end of the last Ice Age, creating favorable conditions for agriculture in this region.

As of 2003, about 3,000 cultural sites have been identified,[6] ranging from small villages to "vast settlements consisting of hundreds of dwellings surrounded by multiple ditches".[15]

Chronology

Periodization

Traditionally separate schemes of periodization have been used for the Ukrainian Trypillian and Romanian Cucuteni variants of the culture. The Cucuteni scheme, proposed by the German archeologist Hubert Schmidt in 1932,[16] distinguished three cultures: Pre-Cucuteni, Cucuteni and Horodiştea-Folteşti; which were further divided into phases (Pre-Cucuteni I-III and Cucuteni A and B).[17] The Ukrainian scheme was first developed by Tatiana Sergeyevna Passek in 1949[18] and divided the Trypillia culture into three main phases (A, B and C) with further sub-phases (BI-II and CI-II).[17] Initially based on informal ceramic seriation, both schemes have been extended and revised since first proposed, incorporating new data and formalised mathematical techniques for artifact seriation.[19](p103)The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is commonly divided into an Early, Middle, Late period, with varying smaller sub-divisions marked by changes in settlement and material culture. A key point of contention lies in how these phases correspond to radiocarbon data. The following chart[17] represents this most current interpretation:

| • Early (Pre-Cucuteni I-III to Cucuteni A-B, Trypillia A to Trypillia BI-II): | 4800 to 4000 BC |

| • Middle (Cucuteni B, Trypillia BII to CI-II): | 4000 to 3500 BC |

| • Late (Horodiştea-Folteşti, Trypillia CII): | 3500 to 3000 BC |

Early period (4800-4000 BC)

Pre-Cucuteni Clay Figures 4900-4750 BC Discovered in Balta Popii, Romania

Some of the Cucuteni-Trypillian copper "Treasure" found at Cărbuna

Clay statues of females and amulets have been found dating to this period. Copper items, primarily bracelets, rings and hooks, are occasionally found as well. A hoard of a large number of copper items (a Treasure - see image) was discovered in the village of Cărbuna, Moldova, consisting primarily of items of jewelry, which were dated back to the beginning of the 5th millennium BC. Some historians have used this evidence to support the theory that a social stratification was present in early Cucuteni culture, but this is disputed by others.[6]

Pottery remains from this early period are very rarely discovered; the remains that have been found indicate that the ceramics were used after being fired in a kiln. The outer color of the pottery is a smoky gray, with raised and sunken relief decorations. Toward the end of this early Cucuteni-Trypillian period, the pottery begins to be painted before firing. The white-painting technique found on some of the pottery from this period was imported from the earlier and contemporary (5th millennium) Gumelniţa-Karanovo culture. Historians point to this transition to kiln-fired, white-painted pottery as the turning point for when the Pre-Cucuteni culture ended and Cucuteni Phase (or Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture) began.[6]

Cucuteni and the neighbouring Gumelniţa-Karanovo cultures seem to be largely contemporary,

"Cucuteni A phase seems to be very long (4600-4050) and covers the entire evolution of Gumelniţa culture A1, A2, B2 phases (maybe 4650-4050)."[22]

Middle period (4000-3500 BC)

In the middle era the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture spread over a wide area from Eastern Transylvania in the west to the Dnieper River in the east. During this period, the population immigrated into and settled along the banks of the upper and middle regions of the Right Bank (or western side) of the Dnieper River, in present-day Ukraine. The population grew considerably during this time, resulting in settlements being established on plateaus, near major rivers and springs.

Archeological finds discovered in Moldova, circa 3650 BC

Tools made of flint, rock, clay, wood and bones continued to be used for cultivation and other chores. Much less common than other materials, copper axes and other tools have been discovered that were made from ore mined in Volyn, Ukraine, as well as some deposits along the Dnieper river. Pottery-making by this time had become sophisticated, however they still relied on techniques of making pottery by hand (the potter's wheel was not used yet). Characteristics of the Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery included a monochromic spiral design, painted with black paint on a yellow and red base. Large pear-shaped pottery for the storage of grain, dining plates, and other goods, was also prevalent. Additionally, ceramic statues of female "Goddess" figures, as well as figurines of animals and models of houses dating to this period have also been discovered.

Some scholars have used the abundance of these clay female fetish statues to base the theory that this culture was matriarchal in nature. Indeed, it was partially the archeological evidence from Cucuteni-Trypillian culture that inspired Marija Gimbutas, Joseph Campbell, and some latter 20th century feminists to set forth the popular theory of an Old European culture of peaceful, matriarchal, Goddess-centered Neolithic European societies that were wiped out by patriarchal, Sky Father-worshipping, warlike, Bronze-Age Proto-Indo-European tribes that swept out of The Steppes east of the Black Sea. This theory has been mostly discredited in recent years,[23] but there are still some people who adhere to it, at least to some degree.

Late period (3500-3000 BC)

During the late period the Cucuteni-Trypillian territory expanded to include the Volyn region in northwest Ukraine, the Sluch and Horyn Rivers in northern Ukraine, and along both banks of the Dnieper river near Kiev. Members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture who lived along the coastal regions near the Black Sea came into contact with other cultures. Animal husbandry increased in importance, as hunting diminished; horses also became more important. The community transformed into a patriarchal structure. Outlying communities were established on the Don and Volga rivers in present-day Russia. Dwellings were constructed differently from previous periods, and a new rope-like design replaced the older spiral-patterned designs on the pottery. Different forms of ritual burial were developed where the deceased were interred in the ground with elaborate burial rituals. An increasingly larger number of Bronze Age artifacts originating from other lands were found as the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture drew near.[6]Decline and end

Main article: Decline and end of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture

There is a debate among scholars regarding how the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture took place.According to some proponents of the Kurgan Hypothesis of the origin of Proto-Indo-European, for example the archaeologist Marija Gimbutas in her book "Notes on the chronology and expansion of the Pit-Grave Culture" (1961, later expanded by her and others), the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture came to a violent end in connection with the territorial expansion of the Kurgan Culture. Arguing from archaeological and linguistic evidence, Gimbutas concluded that the people of the Kurgan culture (a term grouping the Pit Grave culture and its predecessors) of the Pontic steppe, being most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European language, effectively destroyed the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in a series of invasions undertaken during their expansion to the west. Based on this archaeological evidence Gimbutas saw distinct cultural differences between the patriarchal, warlike Kurgan culture and the more peaceful matriarchal Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, which she argued was a significant component of the "Old European cultures" which finally met extinction in a process visible in the progressing appearance of fortified settlements, hillforts, and the graves of warrior-chieftains, as well as in the religious transformation from the matriarchy to patriarchy, in a correlated east-west movement.[24] In this, "the process of Indo-Europeanization was a cultural, not a physical, transformation and must be understood as a military victory in terms of successfully imposing a new administrative system, language, and religion upon the indigenous groups.[25] Accordingly these proponents of the Kurgan Hypothesis hold that this violent clash took place during the Third Wave of Kurgan expansion between 3000-2800 BC, permanently ending the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.

In 1989 Irish-American archaeologist J.P. Mallory in his book "In Search of the Indo-Europeans" summarizing the three existing theories concerning the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, mentions that archaeological findings in the region indicate Kurgan (i.e. Yamna culture) settlements in the eastern part of the Cucuteni-Trypillian area, co-existing for some time with those of the Cucuteni-Trypillian.[4] Artifacts from both cultures found within each of their respective archaeological settlement sites attest to an open trade in goods for a period,[4] though he points out that the archaeological evidence clearly points to what he termed "a dark age," its population seeking refuge in every direction except east. He cites evidence of the refugees having used caves, islands and hilltops (abandoning in the process 600-700 settlements) to argue for the possibility of a gradual transformation rather than a violent onslaught bringing about cultural extinction.[4] The obvious issue with that theory is the limited common historical life-time between the Cucuteni-Trypillian (4800-3000 BC) and the Yamna culture (3600-2300BC); given that the earliest archaeological findings of the Yamna culture (3600-3200 BC) are located in the Volga-Don basin, not in the Dniester and Dnieper area where the cultures came in touch, while the Yamna culture came to its full extension in the Pontic steppe at the earliest around 3000 BC, the time the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ended[26] thus indicating an extremely short survival after coming in contact with the Yamna culture. Another contradicting indication is that the kurgans that replaced the traditional horizontal graves in the area now contain human remains of a fairly diversified skeletal type approximately ten centimeters taller on average than the previous population.[4]

In the 1990s and 2000s, another theory regarding the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture emerged based on climatic change that took place at the end of their culture's existence that is known as the Blytt-Sernander Sub-Boreal phase. Beginning around 3200 BC the earth's climate became colder and drier than it had ever been since the end of the last Ice age, resulting in the worst drought in the history of Europe since the beginning of agriculture.[27] The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture relied primarily on farming, which would have collapsed under these climatic conditions in a scenario similar to the Dust Bowl of the American Midwest in the 1930s.[28] According to The American Geographical Union, "The transition to today's arid climate was not gradual, but occurred in two specific episodes. The first, which was less severe, occurred between 6,700 and 5,500 years ago. The second, which was brutal, lasted from 4,000 to 3,600 years ago. Summer temperatures increased sharply, and precipitation decreased, according to carbon-14 dating. According to that theory, the neighboring Yamna culture people were pastoralists, and were able to maintain their survival much more effectively in drought conditions. This has led some scholars to come to the conclusion that the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture ended not violently, but as a matter of survival, converting their economy from agriculture to pastoralism, and becoming integrated into the Yamna culture.[20][27][28][29] However, the Blytt–Sernander approach as a way to identify stages of technology in Europe with specific climate periods is an oversimplification not generally accepted. A conflict with that theoretical possibility is that during the warm Atlantic period, Denmark was occupied by Mesolithic cultures, rather than Neolithic, notwithstanding the climatic evidence. Moreover, the technology stages varied widely globally. To this must be added that the first period of the climate transformation ended some 500 years before the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and the second approximately 1,400 years after.

Economy

Main article: Economy of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Throughout the 2,750 years of its existence, the Cucuteni-Trypillian

culture was fairly stable and static; however, there were changes that

took place. This article addresses some of these changes that have to do

with the economic aspects. These include the basic economic conditions

of the culture, the development of trade, interaction with other

cultures, and the apparent use of barter tokens, an early form of money.Members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture shared common features with other Neolithic societies, including:

- An almost nonexistent social stratification

- Lack of a political elite

- Rudimentary economy, most likely a subsistence or gift economy

- Pastoralists and subsistence farmers

Like other Neolithic societies, the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture had almost no division of labor. Although this culture's settlements sometimes grew to become the largest on earth at the time (up to 15,000 people in the largest), there is no evidence that has been discovered of labor specialization. Every household probably had members of the extended family who would work in the fields to raise crops, go to the woods to hunt game and bring back firewood, work by the river to bring back clay or fish, and all of the other duties that would be needed to survive. Contrary to popular belief, the Neolithic people experienced considerable abundance of food and other resources.[3] Since every household was almost entirely self-sufficient, there was very little need for trade. However, there were certain mineral resources that, because of limitations due to distance and prevalence, did form the rudimentary foundation for a trade network that towards the end of the culture began to develop into a more complex system, as is attested to by an increasing number of artifacts from other cultures that have been dated to the latter period.[4]

Toward the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture's existence (from roughly 3000 BC to 2750 BC), copper traded from other societies (notably, from the Balkans) began to appear throughout the region, and members of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture began to acquire skills necessary to use it to create various items. Along with the raw copper ore, finished copper tools, hunting weapons and other artifacts were also brought in from other cultures.[3] This marked the transition from the Neolithic to the Eneolithic, also known as the Chalcolithic or Copper Age. Bronze artifacts began to show up in archaeological sites toward the very end of the culture. The primitive trade network of this society, that had been slowly growing more complex, was supplanted by the more complex trade network of the Proto-Indo-European culture that eventually replaced the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture.[3]

Diet

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture was a society of subsistence farmers. Cultivating the soil (using an ard or scratch plough), harvesting crops and tending livestock was probably the main occupation for most people. Typically for a Neolithic culture, the vast[citation needed] majority of their diet consisted of cereal grains. They cultivated club wheat, oats, rye, proso millet, barley and hemp, which were probably ground and baked as unleavened bread in clay ovens or on heated stones in the home. They also grew peas and beans, apricot, cherry plum and wine grapes – though there is no solid evidence that they actually made wine.[30][31] There is also evidence that they may have kept bees.[32]The zooarchaeology of Cucuteni-Trypillian sites indicate that the inhabitants practiced animal husbandry. Their domesticated livestock consisted primarily of cattle, but included smaller numbers of pigs, sheep and goats. There is evidence, based on some of the surviving artistic depictions of animals from Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, that the ox was employed as a draft animal.[30]

Both remains and artistic depictions of horses have been discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites. However, whether these finds are of domesticated or wild horses is debated. Before they were domesticated, humans hunted wild horses for meat. On the other hand, one hypothesis of horse domestication places it in the steppe region adjacent to the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture at roughly the same time (4000–3500 BC), so it is possible the culture was familiar with the domestic horse. At this time horses could have been kept both for meat or as a work animal.[33] The direct evidence remains inconclusive.[34]

Hunting supplemented the Cucuteni-Trypillian diet. They used traps to catch their prey, as well as various weapons, including the bow-and-arrow, the spear, and clubs. To help them in stalking game, they sometimes disguised themselves with camouflage.[33] Remains of game species found at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites include red deer, roe deer, aurochs, wild boar, fox and brown bear.[citation needed]

Salt

The earliest known salt works in the world is at Poiana Slatinei, near the village of Lunca in Romania. It was first used in the early Neolithic, around 6050 BCE, by the Starčevo culture, and later by the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture in the Pre-Cucuteni period.[35] Evidence from this and other sites indicates that the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture extracted salt from salt-laden spring-water through the process of briquetage. First, the brackish water from the spring was boiled in large pottery vessels, producing a dense brine. The brine was then heated in a ceramic briquetage vessel until all moisture was evaporated, with the remaining crystallized salt adhering to the inside walls of the vessel. Then the briquetage vessel was broken open, and the salt was scraped from the shards.[36]The provision of salt was a major logistical problem for the largest Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements. As they came to rely upon cereal foods over salty meat and fish, Neolithic cultures had to incorporate supplementary sources of salt into their diet. Similarly, domestic cattle need to be provided with extra sources of salt beyond their normal diet or their milk production is reduced. Cucuteni-Trypillian mega-sites, with a population of likely thousands of people and animals, are estimated to have required between 36,000 and 100,000 kg of salt per year. This was not available locally, and so had to be moved in bulk from distant sources on the western Black Sea coast and in the Carpathian Mountains, probably by river.[37]

Technology and material culture

The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture is known by its distinctive settlements, architecture, intricately decorated pottery and anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figurines, which are preserved in archaeological remains. At its peak it was one of the most technologically advanced societies in the world at the time,[4] developing new techniques for ceramic production, housing building and agriculture, and producing woven textiles (although these have not survived and are known indirectly).Settlements

Main articles: Settlements of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, Architecture of the Cucuteni–Trypillian culture and House burning of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

In terms of overall size, some of Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, such as Talianki (with a population of 15,000 and covering an area of some 335[38] hectares) in the province of Uman Raion, Ukraine, are as large as (or perhaps even larger than) the more famous city-states of Sumer in the Fertile Crescent, and these Eastern European settlements predate the Sumerian cities by more than half of a millennium.[39]Archaeologists have uncovered an astonishing[peacock term] wealth of artifacts from these ancient ruins. The largest collections of Cucuteni-Trypillian artifacts are to be found in museums in Russia, Ukraine, and Romania, including the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg and the Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamţ in Romania. However, smaller collections of artifacts are kept in many local museums scattered throughout the region.[20]

These settlements underwent periodical acts of destruction and re-creation, as they were burned and then rebuilt every 60–80 years. Some scholars[who?] have theorized that the inhabitants of these settlements believed that every house symbolized an organic, almost living, entity. Each house, including its ceramic vases, ovens, figurines and innumerable objects made of perishable materials, shared the same circle of life, and all of the buildings in the settlement were physically linked together as a larger symbolic entity. As with living beings, the settlements may have been seen as also having a life cycle of death and rebirth.[40][dead link]

The houses of the Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements were constructed in several general ways:

- Wattle and daub homes.

- Log homes, called (Ukrainian: площадки ploščadki).

- Semi-underground homes called Bordei.

Interior reconstruction of a Cucuteni-Trypillian house in the Archaeology Museum Piatra Neamţ, Romania.

|

Reconstruction of a Bronze Age pit-house in the Tripillian Museum, Trypillia, Ukraine.

|

A scale reproduction of a Cucuteni-Trypillian village.

|

Model of Cucuteni house

|

Top view of cucuteni house model

|

Pottery

Decorated Cucuteni-Trypillian pottery

Characteristically vessels were elaborately decorated with swirling patterns and intricate designs. Sometimes decorative incisions were added prior to firing, and sometimes these were filled with colored dye to produce a dimensional effect. In the early period, the colors used to decorate pottery were limited to a rusty-red and white. Later, potters added additional colors to their products and experimented with more advanced ceramic techniques.[6] The pigments used to decorate ceramics were based on iron oxide for red hues, calcium carbonate, iron magnetite and manganese Jacobsite ores for black, and calcium silicate for white. The black pigment, which was introduced during the later period of the culture, was a rare commodity: taken from a few sources and circulated (to a limited degree) throughout the region. The probable sources of these pigments were Iacobeni in Romania for the iron magnetite ore and Nikopol in Ukraine for the manganese Jacobsite ore.[41][42] No traces of the iron magnetite pigment mined in the easternmost limit of the Cucuteni-Trypillian region have been found to be used in ceramics from the western settlements, suggesting exchange throughout the entire cultural area was limited. In addition to mineral sources, pigments derived from organic materials (including bone and wood) were used to create various colors.[43]

In the late period of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, kilns with a controlled atmosphere were used for pottery production. These kilns were constructed with two separate chambers—the combustion chamber and the filling chamber— separated by a grate. Temperatures in the combustion chamber could reach 1000–1100 °C but were usually maintained at around 900 °C to achieve a uniform and complete firing of vessels.[41]

Toward the end of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, as copper became more readily available, advances in ceramic technology leveled off as more emphasis was placed on developing metallurgical techniques.

Ceramic figurines

An anthropomorphic ceramic artifact was discovered during an archaeological dig in 1942 on Cetatuia Hill near Bodeşti, Neamţ County, Romania, which became known as the "Cucuteni Frumusica Dance" (after a nearby village of the same name). It was used as a support or stand, and upon its discovery was hailed as a symbolic masterpiece of Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. It is believed that the four stylized feminine silhouettes facing inward in an interlinked circle represented a hora, or ritualistic dance. Similar artifacts were later found in Bereşti and Drăgușeni.Extant figurines excavated at the Cucuteni sites are thought to represent religious artefacts, but their meaning or use is still unknown. Some historians as Gimbutas claim that:

...the stiff nude to be representative of death on the basis that the color white is associated with the bone (that which shows after death). Stiff nudes can be found in Hamangia, Karanovo, and Cucuteni cultures[44]

Textiles

Reconstructed Cucuteni-Trypillian loom

Other pottery sherds with textile impressions, found at Frumusica[disambiguation needed] and Cucuteni, suggest that textiles were also knitted (specifically using a technique known as nalbinding).[49]

Weapons and tools

A sample of Miorcani flint. One of the most used lithic raw materials at Cucuteni-Trypillian settlements. (ca. 7.5 cm wide)

Stone industry of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Ritual and religion

A typical Cucuteni-Trypillian clay "Goddess" fetish

Main article: Religion and ritual of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture

Some Cucuteni-Trypillian communities have been found that contain a

special building located in the center of the settlement, which

archaeologists have identified as sacred sanctuaries. Artifacts have

been found inside these sanctuaries, some of them having been

intentionally buried in the ground within the structure, that are

clearly of a religious nature, and have provided insights into some of

the beliefs, and perhaps some of the rituals and structure, of the

members of this society. Additionally, artifacts of an apparent

religious nature have also been found within many domestic

Cucuteni-Trypillian homes.Many of these artifacts are clay figurines or statues. Archaeologists have identified many of these as fetishes or totems, which are believed to be imbued with powers that can help and protect the people who look after them.[19] These Cucuteni-Trypillian figurines have become known popularly as Goddesses, however, this term is not necessarily accurate for all female anthropomorphic clay figurines, as the archaeological evidence suggests that different figurines were used for different purposes (such as for protection), and so are not all representative of a Goddess.[19] There have been so many of these figurines discovered in Cucuteni-Trypillian sites[19] that many museums in eastern Europe have a sizeable collection of them, and as a result, they have come to represent one of the more readily identifiable visual markers of this culture to many people.

The noted archaeologist Marija Gimbutas based at least part of her famous Kurgan Hypothesis and Old European culture theories on these Cucuteni-Trypillian clay figurines. Her conclusions, which were always controversial, today are discredited by many scholars,[19] but still there are some scholars who support her theories about how Neolithic societies were matriarchal, non-warlike, and worshipped an "earthy" Mother Goddess, but were subsequently wiped out by invasions of patriarchal Indo-European tribes who burst out of the Steppes of Russia and Kazakhstan beginning around 2500 BC, and who worshiped a warlike Sky God.[51] However, Gimbutas' theories have been partially discredited by more recent discoveries and analyses.[4] Today there are many scholars who disagree with Gimbutas, pointing to new evidence that suggests a much more complex society during the Neolithic era than she had been accounting for.[52]

Further information: Proto-Indo-European Urheimat hypotheses

One of the unanswered questions regarding the Cucuteni-Trypillian

culture is the small number of artifacts associated with funerary rites.

Although very large settlements have been explored by archaeologists,

the evidence for mortuary activity is almost invisible. Making a

distinction between the eastern Trypillia and the western Cucuteni

regions of the Cucuteni-Trypillian geographical area, American

archaeologist Douglass W. Bailey writes:There are no Cucuteni cemeteries and the Trypillia ones that have been discovered are very late.[19](p115)The discovery of skulls is more frequent than other parts of the body, however because there has not yet been a comprehensive statistical survey done of all of the skeletal remains discovered at Cucuteni-Trypillian sites, precise post excavation analysis of these discoveries cannot be accurately determined at this time. Still, many questions remain concerning these issues, as well as why there seems to have been no male remains found at all.[53] The only definite conclusion that can be drawn from archeological evidence is that in the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture, in the vast majority of cases, the bodies were not formally deposited within the settlement area.[19](p116)

Vinča-Turdaş script

Main articles: Symbols and proto-writing of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture and Vinča symbols

The mainstream academic view holds that writing first appeared during the Sumerian civilization in southern Mesopotamia, around 3300–3200 BC. in the form of the Cuneiform script.

This first writing system did not suddenly appear out of nowhere, but

gradually developed from less stylized pictographic systems that used ideographic and mnemonic symbols that contained meaning, but did not have the linguistic flexibility of the natural language writing system that the Sumerians first conceived. These earlier symbolic systems have been labeled as proto-writing, examples of which have been discovered in a variety of places around the world, some dating back to the 7th millennium BC.[54]-

One of the three Tărtăria tablets, dated 5300 BC

-

One of the Gradeshnitsa tablets

Beginning in 1875 up to the present, archaeologists have found more than a thousand Neolithic era clay artifacts that have examples of symbols similar to the Vinča script scattered widely throughout south-eastern Europe. This includes the discoveries of what appear to be barter tokens, which were used as an early form of currency. Thus it appears that the Vinča or Vinča-Turdaş script is not restricted to just the region around Belgrade, which is where the Vinča culture existed, but that it was spread across most of southeastern Europe, and was used throughout the geographical region of the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture. As a result of this widespread use of this set of symbolic representations, historian Marco Merlini has suggested that it be given a name other than the Vinča script, since this implies that it was only used among the Vinča culture around the Pannonian Plain, at the very western edge of the extensive area where examples of this symbolic system have been discovered. Merlini has proposed naming this system the Danube Script, which some scholars have begun to accept.[54] However, even this name change would not be extensive enough, since it does not cover the region in Ukraine, as well as the Balkans, where examples of these symbols are also found. Whatever name is used, however (Vinča script, Vinča-Tordos script, Vinča symbols, Danube script, or Old European script), it is likely that it is the same system.[54]

Archaeogenetics

Further information: Archaeogenetics of Europe

The authors conclude that the population living around Verteba Cave was fairly heterogenous, but that the wide chronological age of the specimens might indicate that the heterogeneity might have been due to natural population flow during this timeframe. The authors also link the pre-HV and HV/V haplogroups with European Paleolithic populations, and consider the T and J haplogroups as hallmarks of Neolithic demic intrusions from the South-East (the North-Pontic region) rather than from the West (i.e. the Linear Pottery culture).[55]

Vinča culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

||

| Alternative names | Turdaş culture Tordos culture Gradeshnitsa culture |

|

|---|---|---|

| Period | Middle Neolithic | |

| Dates | c. 5700–4500 BCE | |

| Type site | Vinča-Belo Brdo | |

| Major sites | Belogradchik Drenovac Gomolava Gornja Tuzla Pločnik Rudna Glava Selevac Tărtăria Turdaş Vratsa Vršac |

|

| Characteristics | Large tell settlements Anthropomorphic figurines Vinča symbols |

|

| ||

An anthropomorphic figurine with incised lines depicting clothing.

The "Tordos" culture was defined by the Hungarian archaeologist Zsófia Torma.[citation needed] It is named for the village of Turdaș (Hungarian: Tordos) in western Romania, which was part of the Kingdom of Hungary at the time.

Contents

Geography and demographics

The Vinča culture occupied a region of Southeastern Europe (i.e. the Balkans) corresponding mainly to modern-day Serbia and Kosovo, but also parts of Romania, Bulgaria, Bosnia, Montenegro, Macedonia, and Greece.[2]This region had already been settled by farming societies of the First Temperate Neolithic, but during the Vinča period sustained population growth led to an unprecedented level of settlement size and density along with the population of areas that were bypassed by earlier settlers. Vinča settlements were considerably larger than any other contemporary European culture, in some instances surpassing the cities of the Aegean and early Near Eastern Bronze Age a millennium later. One of the largest sites was Vinča-Belo Brdo, it covered 29 hectare and had up to 2,500 people.[3]

Early Vinča settlement population density was 50-200 people per hectare, in later phases an average of 50-100 people per hectare was common.[1] The Divostin site 4900-4650 B.C. had up to 1028 houses and a maximum population size of 8200 and could perhaps be the largest Vinča settlement. Another large site was Stubline from 4700 B.C. it may contained a maximum population of 4000. The settlement of Parţa maybe had 1575 people living there at the same time.[4][5][6][7][8][9]

Chronology

The origins of the Vinča culture are debated. Before the advent of radiocarbon dating it was thought, on the basis of typological similarities, that Vinča and other Neolithic cultures belonging to the 'Dark Burnished Ware' complex were the product of migrations from Anatolia to the Balkans. This had to be reassessed in light of radiocarbon dates which showed that the Dark Burnished Ware complex appeared at least a millennium before Troy I, the putative starting point of the westward migration. An alternative hypothesis where the Vinča culture developed locally from the preceding Starčevo culture—first proposed by Colin Renfrew in 1969—is now accepted by many scholars, but the evidence is not conclusive.[10][11]The Vinča culture can be divided into two phases, closely linked with those of its type site Vinča-Belo Brdo:[12]

| Vinča culture | Vinča-Belo Brdo | Years BCE |

|---|---|---|

| Early Vinča period | Vinča A | 5700–4800 |

| Vinča B | ||

| Vinča C | ||

| Late Vinča period | Vinča D | 4800–4200 |

| Abandoned |

Decline

In its later phase the centre of the Vinča network shifted from Vinča-Belo Brdo to Vršac, and the long-distance exchange of obsidian and Spondylus artefacts from modern-day Hungary and the Aegean respectively became more important than that of Vinča figurines. Eventually the network lost its cohesion altogether and fell into decline. It is likely that, after two millennia of intensive farming, economic stresses caused by decreasing soil fertility were partly responsible for this decline.[13]According to Marija Gimbutas, the Vinča culture was part of Old Europe – a relatively homogeneous, peaceful and matrifocal culture that occupied Europe during the Neolithic. According to this hypothesis its period of decline was followed by an invasion of warlike, horse-riding Proto-Indo-European tribes from the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[14]

Economy

Subsistence

Most people in Vinča settlements would have been occupied with the provision of food. They practised a mixed subsistence economy where agriculture, animal husbandry and hunting and foraging all contributed to the diet of the growing Vinča population. Compared to earlier cultures of the First Temperate Neolithic (FTN) these practices were intensified, with increasing specialisation on high-yield cereal crops and the secondary products of domesticated animals, consistent with the increased population density.[15]Vinča agriculture introduced common wheat, oat and flax to temperate Europe, and made greater use of barley than the cultures of the FTN. These innovations increased crop yields and allowed the manufacture of clothes made from plant textiles as well as animal products (i.e. leather and wool). There is indirect evidence that Vinča farmers made use of the cattle-driven plough, which would have had a major effect on the amount of human labour required for agriculture as well as opening up new area of land for farming. Many of the largest Vinča sites occupy regions dominated by soil types that would have required ploughing.[15]

Areas with less arable potential were exploited through transhumant pastoralism, where groups from the lowland villages moved their livestock to nearby upland areas on a seasonal basis. Cattle was more important than sheep and goats in Vinča herds and, in comparison to the cultures of the FTN, livestock was increasingly kept for milk, leather and as draft animals, rather than solely for meat. Seasonal movement to upland areas was also motivated by the exploitation of stone and mineral resources. Where these were especially rich permanent upland settlements were established, which would have relied more heavily on pastoralism for subsistence.[15]

Though increasingly focused on domesticated plants and animals, the Vinča subsistence economy still made use of wild food resources. The hunting of deer, boar and aurochs, fishing of carp and catfish, shell-collecting, fowling and foraging of wild cereals, forest fruits and nuts made up a significant part of the diet at some Vinča sites. These, however, were in the minority; settlements were invariably located with agricultural rather than wild food potential in mind, and wild resources were usually underexploited unless the area was low in arable productivity.[15]

Industry

Generally speaking craft production within the Vinča network was carried out at the household level; there is little evidence for individual economic specialisation. Nevertheless, some Vinča artefacts were made with considerable levels of technical skill. A two-stage method was used to produce pottery with a polished, multi-coloured finish, known as 'Black-topped' and 'Rainbow Ware'. Sometimes powdered cinnabar and limonite were applied to the fired clay for decoration. The style of Vinča clothing can be inferred from figurines depicted with open-necked tunics and decorated skirts. Cloth was woven from both flax and wool (with flax becoming more important in the later Vinča period), and buttons made from shell or stone were also used.[16]The Vinča site of Pločnik has produced the earliest example of copper tools in the world. However, the people of the Vinča network practised only an early and limited form of metallurgy.[17] Copper ores were mined on a large scale at sites like Rudna Glava, but only a fraction were smelted and cast into metal artefacts – and these were ornaments and trinkets rather than functional tools, which continued to be made from chipped stone, bone and antler. It is likely that the primary use of mined ores was in their powdered form, in the production of pottery or as bodily decoration.[16]

Yamna culture

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|

| Geographical range | Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Bronze Age |

| Dates | c. 3500 BC – 2000 BC |

| Preceded by | Maykop culture |

| Followed by | Andronovo culture |

Approximate culture extent c. 3200-2300 BC.

| Part of a series on |

| Indo-European topics |

|---|

The culture was predominantly nomadic, with some agriculture practiced near rivers and a few hillforts.[1]

The Yamna culture was preceded by the Sredny Stog culture, Khvalynsk culture and Dnieper-Donets culture, while succeeded by the Catacomb culture and the Srubna culture.

Contents

Characteristics

Characteristic for the culture are the inhumations in kurgans (tumuli) in pit graves with the dead body placed in a supine position with bent knees. The bodies were covered in ochre. Multiple graves have been found in these kurgans, often as later insertions.[citation needed]Significantly, animal grave offerings were made (cattle, sheep, goats and horse), a feature associated with Proto-Indo-Europeans .[2]

The earliest remains in Eastern Europe of a wheeled cart were found in the "Storozhova mohyla" kurgan (Dnipropetrovsk, Ukraine, excavated by Trenozhkin A.I.) associated with the Yamna culture.

Spread and identity

The Yamna culture is identified with the late Proto-Indo-Europeans (PIE) in the Kurgan hypothesis of Marija Gimbutas. It is the strongest candidate for the Urheimat (homeland) of the Proto-Indo-European language, along with the preceding Sredny Stog culture, now that archaeological evidence of the culture and its migrations has been closely tied to the evidence from linguistics[3] and genetics.[4][5]Pavel Dolukhanov argues that the emergence of the Pit-Grave culture represents a social development of various local Bronze Age cultures, representing "an expression of social stratification and the emergence of chiefdom-type nomadic social structures", which in turn intensified inter-group contacts between essentially heterogeneous social groups.[6]

It is said to have originated in the middle Volga based Khvalynsk culture and the middle Dnieper based Sredny Stog culture.[citation needed] In its western range, it is succeeded by the Catacomb culture; in the east, by the Poltavka culture and the Srubna culture.

Genetics

DNA from the remains of nine individuals associated with the Yamna culture from Samara Oblast and Orenburg Oblast has been analyzed. The remains have been dated to 2700–3339 BCE. Y-chromosome sequencing revealed that one of the individuals belonged to haplogroup R1b1-P25 (the subclade could not be determined), one individual belonged to haplogroup R1b1a2a-L23 (and to neither the Z2103 nor the L51 subclades), and five individuals belonged to R1b1a2a2-Z2103. The individuals belonged to mtDNA haplogroups U4a1, W6, H13a1a1a, T2c1a2, U5a1a1, H2b, W3a1a and H6a1b. A 2015 genome wide study of 94 ancient skeletons from Europe and Russia concluded that Yamnaya autosomal characteristics are very close to the Corded Ware culture people with an estimated a 73% ancestral contribution from the Yamnaya DNA in the DNA of Corded Ware skeletons from Germany. The same study estimated a 40-54% ancestral contribution of the Yamnaya in the DNA of modern Central & Northern Europeans, and a 20–32% contribution in modern Southern Europeans, excluding Sardinians (7,1% or less) and to a lessor extent Sicilians (11,6% or less).[4][7][8]Kurgan stelae

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Anthropomorphic stele of the early type (Neolithic period) from Hamangia-Baia, Romania exhibited at Histria Museum

Spanning more than three millennia, they are clearly the product of various cultures. The earliest are associated with the Pit Grave culture of the Pontic-Caspian steppe (and therefore with the Proto-Indo-Europeans according to the mainstream Kurgan hypothesis[2]). There are Iron Age specimens are identified with the Scythians and medieval examples with Turkic peoples.

Such stelae are found in large numbers in Southern Russia, Ukraine, Prussia, southern Siberia, Central Asia and Mongolia.

Contents

Purpose

Anthropomorphic stelae were probably memorials to the honoured dead.[3] They are found in the context of burials and funeral sanctuaries from the Eneolithic through to the Middle Ages. Ivanovovsky reported that Tarbagatai Torgouts (Kalmyks) revered kurgan obelisks in their country as images of their ancestors, and that when a bowl was held by the statue, it was to deposit a part of the ashes after the cremation of the deceased, and another part was laid under the base of the statue.[4]When used architecturally, stelae could act as a system of stone fences, frequently surrounded by a moat, with sacrificial hearths, sometimes tiled on the inside.

History and distribution

The simple, early type of anthropomorphic stelae are also found in the Alpine region of Italy, southern France and Portugal.[8] Examples have also been found in Bulgaria at Plachidol, Vezevero,[9] and Durankulak.[10] The example illustrated above was found at Hamangia-Baia, Romania.

The distribution of later stelae is limited in the west by the Odessa district, Podolsk province, Galicia, Kalisz province, Prussia; in the south by Kacha River, Crimea; in the south-east by Kuma River in the Stavropol province and Kuban region; in the north by Minsk province and Oboyan district of the Kursk province (in some opinions even the Ryazan province), Ahtyr district in the Kharkov province, Voronej province, Balash and Atkar districts in the Saratov province to the banks of Samara River in Buzuluk districts in the Samara province, in the east they are spread in the Kyrgyz (Kazakh) steppe to the banks of the Irtysh River and to Turkestan (near Issyk Kul, Tokmak district), then in upper courses of rivers Tom and Yenisei, in Sagai steppe in Mongolia (according to Potanin and Yadrintseva).

The Cimmerians of the early 1st millennium BC left a small number (about ten are known) of distinctive stone stelae. Another four or five "deer stones" dating to the same time are known from the northern Caucasus.

From the 7th century BC, Scythian tribes began to dominate the Pontic steppe. They were in turn displaced by the Sarmatians from the 2nd century BC, except in Crimea, where they persisted for a few centuries longer. These peoples left carefully crafted stone stelae, with all features cut in deep relief.

Early Slavic stelae are again more primitive. There are some thirty sites of the middle Dniestr region where such anthropomorphic figures were found. The most famous of these is the Zbruch Idol (c. 10th century), a post measuring about 3 meters, with four faces under a single pointed hat (c.f. Svetovid). Boris Rybakov argued for identification of the faces with the gods Perun, Makosh, Lado and Veles.

Anthropomorphic stelae of the Near East

Bronze Age anthropomorphic funerary stelae have been found in Saudi Arabia. There are similarities to the Kurgan type in the handling of the slab-like body with incised detail, though the treatment of the head is rather more realistic.[11]The anthropomorphic stelae so far found in Anatolia appear to post-date those of the Kemi Oba culture on the steppe and are presumed to derive from steppe types. A fragment of one was found in the earliest layer of deposition at Troy, known as Troy I.[12]

Thirteen stone stelae, of a type similar to those of the Eurasian steppes, were found in 1998 in their original location at the centre of Hakkâri, a city in the south eastern corner of Turkey, and are now on display in the Van Museum. The stelae were carved on upright flagstone-like slabs measuring between 0.7 m to 3.10 m in height. The stones contain only one cut surface, upon which human figures have been chiseled. The theme of each stele reveals the fore view of an upper human body. Eleven of the stelae depict naked warriors with daggers, spears, and axes-masculine symbols of war. They always hold a drinking vessel made of skin in both hands. Two stelae contain female figures without arms. The earliest of these stelae are in the style of bas relief while the latest ones are in a linear style. They date from the 15th to the 11th century BC and may represent the rulers of the kingdom of Hubushkia, perhaps derived from a Eurasian steppe culture that had infiltrated into the Near East.[13]

Recording

European traveler William of Rubruck mentioned them for the first time in the 13th century, seeing them on kurgans in the Cuman (Kipchak) country, he reported that Cumans installed these statues on tombs of their deceased. These statues are also mentioned in the 17th-century "Large Drawing Book", as markers for borders and roads, or orientation points. In the 18th century information about some kurgan stelae was collected by Pallas, Falk, Guldenshtedt, Zuev, Lepekhin, and in the first half of the 19th century by Klaprot, Duboa-de-Montpere and Spassky (Siberian obelisks). Count Aleksey Uvarov, in the 1869 ‘‘Works of the 1st Archeological Congress in Moscow (vol. 2), assembled all available at that time data about kurgan obelisks, and illustrated them with drawings of 44 statues.Later in the 19th century, data about these statues was gathered by A.I. Kelsiev, and in Siberia, Turkestan and Mongolia by Potanin, Pettsold, Poyarkov, Vasily Radlov, Ivanov, Adrianov and Yadrintsev, in Prussia by Lissauer and Gartman.

Scythian 5th to 4th century BC. Salbyk kurgan surrounded by balbals with

kurgan obelisk on the top. Photographed before excavation, early

20th-century, Minusinsk territory, Siberia

Numbers

The Historical museum in Moscow has 30 specimens (in the halls and in the courtyard); others are in Kharkov, Odessa, Novocherkassk, etc. These are only a small part of examples dispersed in various regions of Eastern Europe, of which multitudes were already destroyed and used as construction material for buildings, fences, etc.In the 1850s Piskarev, summing all information about kurgan obelisks available in literature, counted 649 items, mostly in Ekaterinoslav province (428), in Taganrog (54), in Crimea province (44), in Kharkov (43), in the Don Cossacks land (37), in Yenisei province, Siberia (12), in Poltava (5), in Stavropol (5), etc.; but many statues remained unknown to him.

Appearance

Collection of drawings of Scythian stelae, ranging from c. 600 BC to AD 300

Kurgan stelae (baba) near Luhansk

Writing about Altai kurgans, L.N. Gumilev states: "To the east from the tombs are standing chains of balbals, crudely sculpted stones implanted in the ground. Number of balbals at the tombs I investigated varies from 0 to 51, but most often there are 3–4 balbals per tomb". Similar numbers are also given by L. R. Kyzlasov.[14] They are memorials to the feats of the deceased, every balbal represents an enemy killed by him. Many tombs have no balbals. Apparently, there are buried ashes of women and children.

Balbals have two clearly distinct forms: conic and flat, with shaved top. Considering the evidence of Orkhon inscriptions that every balbal represented a certain person, such distinction cannot be by chance. Likely here is marked an important ethnographic attribute, a headdress. The steppe-dwellers up until present wear a conic 'malahai', and the Altaians wear flat round hats. The same forms of headdresses are recorded for the 8th century.[15] Another observation of Lev Gumilev: "From the Tsaidam salt lakes to the Kül-tegin monument leads a three-kilometer chain of balbals. To our time survived 169 balbals, apparently there were more. Some balbals are given a crude likeness with men, indicated are hands, a hint of a belt. Along the moat toward the east runs a second chain of balbals, which gave I. Lisi a cause to suggest that they circled the fence wall of the monument. However, it is likely that it is another chain belonging to another deceased buried earlier".[16]