By NCC Staff

11 hours ago

By NCC Staff

11 hours ago Britain marks 800th anniversary of Magna Carta signing

On June 15,

1215, in a field at Runnymede, King John agree to place the royal seal

to Magna Carta. The King had been confronted by 40 barons, who issued

their demands to avoid a civil war. (Pope Innocent III soon nullified

the agreement, and war broke out anyway within England.)

The

Magna Carta established the concept that the King was not above the law

of the realm. It also led to some familiar concepts in the U.S.

Constitution, such as due process.

“No

freeman shall be taken, imprisoned, disseised, outlawed, banished, or

in any way destroyed, nor will We proceed against or prosecute him,

except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land,”

the Magna Carta read.

The 800-year Magna Carta anniversary celebrations started in February and they will continue through 2015.

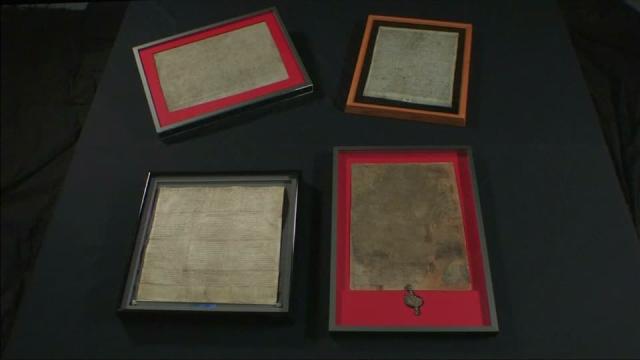

The

British Library started a special exhibition in March that paired its

two Magna Carta copies from 1215 with two of America’s founding

documents: the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence. The

British Library has Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten copy of the

Declaration and one of 12 original copies of the Bill of Rights at the

exhibition, called Magna Carta: Law, Liberty, Legacy, which is set to

run to September 1, 2015.

In addition to due process, the Magna Carta expressed the concept of higher law, or the law of the land, which meant that not even the king, or a legislature, was above the law.

While the Magna Carta’s birthday is a huge deal in the United Kingdom, with Queen Elizabeth involved in the ceremonies, not all English legal experts are fans of the document.

Lord Sumption, a member of the U.K.’s Supreme Court and a medieval historian, has called the Magna Carta “turgid,” and very limited in how it affected people’s lives.

“Magna

Carta matters, if not for the reasons commonly put forward. Some

documents are less important for what they say than for what people

wrongly think that they say,” he said in March 2015 address at the British Library.

“The point is that we have to stop thinking about it just as a medieval

document. It is really a chapter in the constitutional history of

seventeenth century England and eighteenth century America.”

No comments:

Post a Comment