https://www.yahoo.com/health

The

academic path of sought-after college basketball player Brandon Austin

is riddled with recruitment, scholarships, and sexual assault

allegations. His story sheds light on how colleges can — and do —

unknowingly recruit students who could be a danger to female students. (Photo: Wikipedia)

The University of Oregon reached an $800,000 settlement last week with a student who says she was gang-raped by three members of the school’s basketball team.

According to the plaintiff,

during a night of drinking she entered a bathroom at a party with three

members of the team. She says at that point, she was gang-raped in the

bathroom and then later in a bedroom; the accused admitted to group

sexual activity but insisted that it was consensual.

The story is disturbing enough, but there’s a twist.

The student filed a suit

against the university in January for violation of her Title IX rights,

for having recruited to its basketball team a student who had been

charged with sexual assault at another college — who then, along with

two of his teammates, she says, went on to rape her at the University of

Oregon.

Title IX is a federal law that prohibits discrimination on the basis of gender in any federally funded education program.

“Deliberate indifference” to student safety

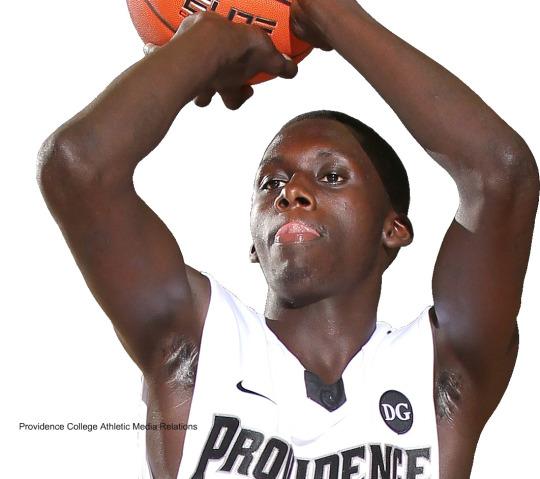

Brandon Austin, the student in question, was charged with sexual assault at Providence College in 2013,

where he was also a member of the school’s basketball team. As in the

University of Oregon incident, the alleged sexual assault at Providence

College also involved Austin and another team member. Criminal

charges were not brought against him, and he was allowed to withdraw

from the school — and that made it possible for him to then be recruited

for the University of Oregon’s team. (The other man accused at

Providence College, Rodney Bullock, chose to stay at the college and

continues to play for its basketball team.)

Brandon Austin (Photo: Providence College Athletic Media Relations)

Once at Oregon, Austin reportedly quickly acclimated to life in a new part of the country and alongside a new team.

According to the police report,

the female student was at an off-campus house party when she was

approached by four men. One of the group left, but the other three

remained. They then complimented her and led her down a hall and into a

bathroom. She told a friend that she had to hold her shorts on, because

Austin and one of the other men kept trying to pull them down, and that

Austin took her cell phone from her when she attempted to use it to call

a friend.

“Brandon was the most physical” and “the most forceful,” the University of Oregon student told officers during the rape investigation.

Related: Court Ruling Highlights Flaws in College Sexual Assault Proceedings — Will It Ripple Across U.S.?

In

her suit, the student — called Jane Doe for privacy purposes — accused

University of Oregon head coach Dana Altman of showing “deliberate

indifference” to student safety by recruiting a student who had

previously faced sexual assault allegations and then went on to commit a

gang-rape at his new school.

In

June 2014, Austin and teammates Dominic Artis and Damyean Dotson were

found responsible by the university for the gang rape of Jane Doe in

March of that year. All three men, including Austin, were allowed to

continue to play for the University of Oregon’s basketball team —

including participation in the NCAA March Madness games — while the

investigation was continuing. It wasn’t until Jane Doe’s allegations

were made public that the men left the school, and even then — as with

Austin at Providence College — they were not expelled.

Rather,

they were banned from the university for 10 years and allowed to

withdraw. All three have since been recruited for other college

basketball teams, seemingly re-creating a tragic, dangerous pattern.

Brandon

Austin was recruited by Northwest Florida State College, where he was

awarded a basketball scholarship. Artis and Dotson continue to play for

Division I teams; Artis now attends and plays basketball for the University of Texas at El Paso (UTEP), and Dotson now attends and plays basketball for the University of Houston.

Austin

recently told CBS Sports that having to play for a smaller school with

less name recognition like Northwest Florida State “humbled me. I know

I’m better than that level. It’s just been really a humbling

experience.”

“I’m a changed person. I went through some stuff that got me stronger and got me smarter,” Austin said.

Are schools conducting investigations required by Title IX?

“I

think the issue that we hear about most frequently from young women

across the country is that too often, schools are not conducting

investigations as is required by Title IX,” says Neena Chaudhry, senior counsel at the National Women’s Law Center

(NWLC) and an expert on Title IX cases. “The process is not transparent

to everybody, and there is not enough action when people are found

responsible for sexual assault. Title IX requires allegations to be

investigated thoroughly and in a timely manner. There needs to be a fair

process in place so that it’s clear — so that [students] know what to

do to report an assault, how to get services [such as counseling and

environmental accommodations regarding housing and class enrollment] —

and that it’s clear that any form of retaliation is prohibited.”

The University of Oregon originally had filed a countersuit

against Jane Doe in February of this year, claiming that her

allegations would deter other victims from coming forward, but

eventually dropped the suit after being met with intense backlash on

campus and in national media.

A complicated situation

When

it comes to instances like what happened at the University of Oregon

and Providence College with Brandon Austin, however, the situation is

complicated. Austin was never found responsible for an instance of

sexual assault at Providence College and was able to voluntarily

withdraw from the school before the conclusion of any Title IX

investigation into the allegations.

“A

school often embraces the outcome of a student voluntarily withdrawing,

the same way a prosecutor embraces a plea bargain,” Scott Berkowitz,

president of the Rape, Abuse, and Incest National Network

(RAINN) tells Yahoo Health. “It ends everything and takes the

responsibility off their plate. Schools breathe a sigh of relief if the

accused agrees to withdraw voluntarily.”

Another

problem, explains Berkowitz, is that because an internal Title IX

investigation is completely independent from any kind of criminal

investigation, it also cannot implement the kind of criminal sentencing

that results in prison time, which Berkowitz says is “the only way to

get perpetrators off the streets and to protect future victims.”

Furthermore,

he notes, “if a student withdraws before being found responsible [for

sexual assault] — that’s a complicated area of law regarding student

privacy,” particularly in terms of what one university may communicate

to another about that student and any allegations raised against him.

“One

challenge in all of this is that even if [allegations and findings of

responsibility] are communicated from one school to another, unless

there is a criminal charge and actual jail time — even if there is a

finding of responsibility by a university, it just moved the problem

somewhere else. That person is still either in the school community or

in a nearby community. You don’t have anything to stop them.”

If

a student is found responsible for sexual assault on a campus, that

school is obligated under Title IX to make sure that steps are taken to

ensure the safety of the school community, such as providing additional

supervision and counseling for the perpetrator, explains Chaudhry.

“They do have an obligation to protect and prevent harassment,” she says, especially when the school knows of a student’s past.

Chaudhry

says the National Women’s Law Center has been involved with a number of

Title IX cases at the high school level in which the courts have held

schools responsible when they know about a person’s previous record in a

way that suggests that the school should increase supervision of that

student and then fail to do so.

She

notes that while it is important to “make sure that the process is fair

to everybody — you want to make sure that students aren’t being

unfairly branded if you don’t know the full facts,” it is always

important for schools to be fair and thoughtful in their investigations

and subsequent actions. “They do have an obligation to protect and

prevent harassment” on their campuses — which is why making sure that

additional supervision for offenders can be so critical.

No standardized system

Chaudhry

also explains that when it comes to Title IX investigations, there is

no standardized system of disciplinary measures that can be invoked by

universities across the board. Just as in instances of cheating and of

nonsexual assault, each school typically has its own honor code and

subsequent sanctions for different kinds of offenses.

“The

worst thing a school can do is expel a student,” adds Berkowitz, in

which case “a criminal case, if successful, ends in prison time most of

the time” for those found responsible for sexual assault.

The

differences in the kinds of sanctions that can be imposed by a

university and the criminal justice system are just one of the many

differences that exist between an internal, university-led Title IX

investigation and a criminal investigation.

Related: The Sad Truth About Marital Rape

“It’s

an entirely separate process,” explains Chaudhry. “Students can file

charges with the police in addition to Title IX. Title IX applies to

school and educational programs — that’s why it’s so important, why they

are required to conduct their own investigations. It’s a school’s job

to prevent sexual harassment. Even if there is a parallel [criminal]

complaint going on, [that investigation] does not reflect the

environment on campus. … The school has an obligation for keeping

students safe. …. A police investigation won’t touch on accommodations

for students [who are the victims of sexual assault], for example, if

they are sharing a class or a dorm with [the accused]. The school’s

process can handle the educational environment — as it should.”

She

notes that often, and wrongly, however, a school may not investigate

sexual assault allegations if it hears that a student has filed criminal

charges, “because they think the police are handling it. But they have

an independent obligation to investigate and address a hostile

educational environment created when these situations happen and protect

students at large.”

“It

was a pretty egregious case,” concludes Berkowitz of the incident at

the University of Oregon. “I am glad to see that the student who was

harmed there got a settlement, and hopefully that will be a pretty big

warning that will stop other schools from making the same mistake. It

will make schools more cautious” about both the precautions taken when

students with a history of assault are on campus and about “protecting

the privacy of victims.”

Requests for comment from the University of Oregon and Northwest Florida State College were not returned.

No comments:

Post a Comment