The oddest fighter plane you've ever seen: Radical low cost twin tailed design is so manoeuverable it 'can rival helicopters'

- Design is already widely used as a border control craft

- Military variant of the plane is called 'Mwari', will be on market in 15 months

- Cost set at $10 million in 2011, but no price given with systems in place

- Aiming to produce 10 aircraft each year, with the potential to hit 20 to 25

It

is one of the oddest plane designs ever created - a tiny

propeller-driven craft with twin tails and two pilots sitting almost on

top of each other.

However,

Boeing and a South Africa's Paramount Group firm hope the wacky

design, currently used to patrol borders, could be turned into a low

cost fighter plane.

The

two firms plan to add missiles and a slew of sensors to the advanced,

high-performance, reconnaissance, light aircraft, which has been

named Mwari after an all-seeing mythological being in Southern African

folklore.

The advanced, high-performance,

reconnaissance, light aircraft is a high-wing aircraft, with stadium

seating for pilot and sensor operator and tops out at 310 mph. The duo

will strap the planes with weapons and use Boeing’s mission system,

which will allow this variant to hunt insurgents, poachers and respond

to conflicts

The

advanced, high-performance, reconnaissance, light aircraft (AHRLAC) is a

high-wing aircraft, with stadium seating for the pilot and sensor

operator and tops out at 310 mph.

The

duo will strap the planes with weapons and use Boeing’s mission

systems, which will allow this military variant to hunt insurgents,

poachers and respond to low-intensity conflicts.

This

announcement was unveiled at the Global Aerospace Summit in Abu Dhabi

this week, as both firms motioned to expand their 2014 agreement to

cooperate on an advanced mission system for AHRLAC.

Boeing

will use its capabilities to design a mission system that will

integrate the avionics and payload systems on the safety-and-security

variant of the AHRLAC, as well as the weapons on the military version,

which has been named Mwari after an all-seeing mythological being in

Southern African folklore.

'Through

AHRLAC, we'll not only bring a flexible, persistent and affordable

aircraft to the international market, but we'll also be developing

world-class technology in Africa,' Jeffrey Johnson, vice president,

Business Development, Boeing Military Aircraft, said.

'Our relationship with Paramount will help us access markets that are new to Boeing.'

Paramount

developed the AHRLAC program five years ago and now believes it has the

ability to take over part of the helicopter market, reports DefenseNews.

'I

think this thing is going to hit the helicopter industry because there

are a lot of roles that this aircraft can fulfill that are fulfilled by

helicopters,' said Paramount's Group Executive Chairman Ivor Ichikowitz.

'It

runs much quieter, it has a very low loiter speed, it's much cheaper to

operate and in some cases it's a much more stable platform than a

helicopter'.

Boeing has been watching the aircraft and believes they found a great opportunity in a market different from their own.

'Boeing

has a worldwide footprint in parts and field services and logistics

that we hope we can utilize too in our portfolio of products from very

high-end costly fighters all the way down to very cost effective

products,' said Johnson.

'This now helps us with market access to a market that we have never been involved in.'

In

2011, Ichikowitz estimated the cost of the variant to be under $10

million, but did not mention the price after Boeing's systems are

implemented.

'Numerous factors will make the AHRLAC unique and a success', he said.

Boeing will

use its capabilities to design a mission system

that will integrate the

avionics and payload systems on the

safety-and-security variant of the

AHRLAC, as well as the

weapons on the military version, which has been named

weapons on the military version, which has been named

Mwari after an all-seeing mythological being in

Southern African

folklore

'It

was designed with our African experience in mind and one of the things

is the cost of support infrastructure; this aircraft requires absolutely

no ground support to operate.'

The operating costs are very low and the aircraft uses a Pratt Whitney PT6 engine that does not need a large amount of support.

'We

have seen many examples around the world of customers buying very

expensive aircraft but not being able to operate them,' said Ichikowitz

This announcement was unveiled at the

Global Aerospace Summit, as both firms motioned to expand their 2014

agreement to cooperate on an advanced mission system for AHRLAC. In

2011, Ichikowitz estimated the cost of the variant to be under $10

million, but did not mention the price after Boeing's systems are in

'Our

objective here is to make the aircraft as cost effective as possible so

it can make its flight hours without needing much support.'

Ichikowitz

also explained that the maintenance cost for the redesign will be

easily managed and a program will be created to predetermine costs for

customers.

One

of the main issues with this variant is the 'multiple configurations of

the platform,' which has a pod system in place and advanced interface

box that enables plug and play of numerous systems, he explained.

The aircraft is capable for light attack roles, ISR role and general policing roles.

Paramount

developed the AHRLAC program five years ago and

now believes it has the

ability to take over part of the helicopter

market. The operating costs

are very low and the aircraft uses a

Pratt Whitney PT6 engine that does

not need a large amount of support

Production

for the fighter plane will ramp up over the next the next year and the

firm is close to finalizing a contract with a launch customer.

'The

programme has moved from inception to laying the foundation stone of

the factory in less than five years, The aircraft will be in the market

in the next 14-15 months. We have had a huge amount of interest from the

Middle East,' said Ichikowitz.

The flight test program is 'nearly complete' and the 'first few' variant will begin testing the mission system, reports Flightglobal.

The firm is aiming to produce 10 aircraft each year, with the potential to hit 20 to 25.

Production for the fighter plane will

ramp up over the next the next year and the firm is close to finalizing a

contract with a launch customer. The flight test program is 'nearly

complete' and the 'first few' variant will begin testing the mission

system, reports Flightglobal

'This is a momentous milestone in AHRLAC's evolution,' said Ichikowitz.

'The multirole aircraft will become a significant player in the global aerospace industry.'

'We

believe in the commercial success of the aircraft and its impact on the

future of the African aerospace industry by boosting advanced

technologies, job creation and skills development.'

Read more:

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/

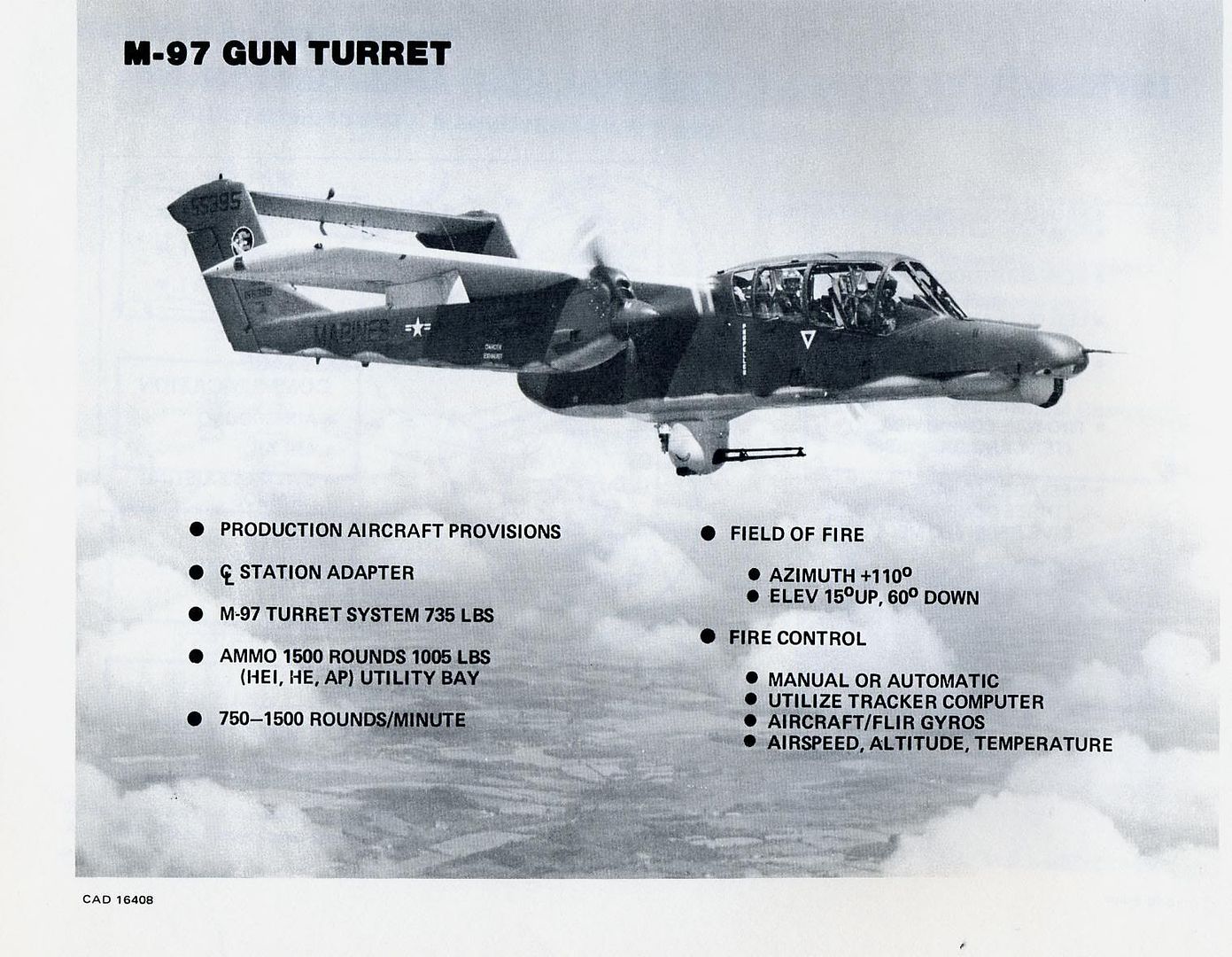

Vintage attack planes used in Vietnam are brought out of retirement to help US special forces defeat ISIS in Iraq

- OV-10 Broncos completed 120 combat missions over 82 days last year

- Believed to have been used as cover for troops who were on the ground

- Central Command said planes were involved in Operation Inherent Resolve

Two vintage planes used in the Vietnam War have been brought out of retirement to help US special forces in Iraq.

A

pair of OV-10 Broncos completed 120 combat missions over the Middle

East between May and September last year, it has been revealed.

The

turbo-prop jet is thought to have carried out 134 sorties over 82 days

in May, acting as cover for the soldiers fighting ISIS terrorists on the

ground.

OV-10 Broncos were used in the Vietnam War and have been brought

out of retirement to help US forces in Iraq

US

Central Command would not confirm where they were based or the targets

they attacked but said they were part of Operation Inherent Resolve, the

American led operation against the extremists in Syria and Iraq.

The

planes, which can take off at very short notice and fly very low, could

be being used to assist American special forces, the Daily Beast reported.

The

armament that can be fitted onto the plane includes, but is not limited

to, machine guns carrying 2,000 rounds and Sidewinder air-to-air

missiles.

They are thought to use this armament to gun down the extremists before they have a chance to flee the ground troops.

The

US military is testing the Broncos in Iraq and Syria to see if they can

replace the more expensive F-15s and F/A-18s which carry out most of

the airstrikes in the countries, Central Command spokesman Force Captain

P Bryant Davis told the Daily Beast.

Whereas an F-15 can cost up to $40,000 per flight, a Bronco can operate for just $1,000 for every hour it is in the air.

The armament that

can be fitted onto the OV-10 (pictured) includes,

but is not limited

to, machine guns carrying 2,000 rounds and

Sidewinder air-to-air

missiles

Whereas an F-15 can cost up to $40,000

per flight, a Bronco (pictured) can operate for just $1,000 for every

hour it is in the air

The

OV-10, developed by the US as a small and cheap attack plane in the

1960s, was first used in Vietnam because they could take off from rough

airfields near to the battlefront.

The

Navy retired its Broncos conflict and the Air Force replaced them with

jet powered A-10 aircraft until they too dropped them in the 1990s.

But 30 years after the Vietnam War, the Americans called on them yet again for the conflicts in Afghanistan and Iraq.

The

military's decision to plough $20million into the OV-10s in 2012 was

blasted by many, including former presidential candidate John McCain who

said 'there is no urgent operational requirement for this type of

aircraft'.

The jets completed 99 per cent of their missions during their 82 days of combat, Davis said.

Now,

Lieutenant General Bradley Heithold, the head of the Air Force Special

Operations Command, has suggested they will continued to be used in

attack missions.

The aircraft made its debut in Vietnam in July 1965.

Bombing

raid commanders known as forward air controllers used OV-10s to make

observations in preparation for air raids during the conflict in

Vietnam.

The Broncos were replaced by the jet powered A-10 Tankbuster aircraft

(pictured) also known as the Warthog.

The aircraft's first flight was in

July 1965 and they were mainly used for observations and light attacks

during the Vietnam War (above)

The highly-adaptable planes proved highly successful and performed dozens of missions for the US Navy and Air Force.

Eighty-one Broncos were lost during Vietnam but the aircraft have continued to be used by forces across the world ever since.

The planes can carry two crew members and have a maximum speed of 281mph.

The

two that have been used in Iraq and Syria are thought to have come from

Nasa, who snapped up the retired planes to carry out airborne tests, or

the State Department, who had sent Broncos to Columbia in a bid to

crackdown on drugs.

http://www.thedailybeast.com

03.08.16 11:01 PM ET

David Axe

David Axe

Why Is America Using These Antique Planes to Fight ISIS?

The U.S. military is testing a dependable, rugged little vintage bomber as it battles elusive ISIS militants in Syria and Iraq.

War

was just an experiment for two of the U.S. military’s oldest and most

unusual warplanes. A pair of OV-10 Broncos—small, Vietnam War-vintage,

propeller-driven attack planes—recently spent three months flying top

cover for ground troops battling ISIS militants in the Middle East.

The OV-10s’ deployment is one of the latest examples of a remarkable phenomenon. The United States—and, to a lesser extent, Russia—has

seized the opportunity afforded it by the aerial free-for-all over Iraq

and Syria and other war zones to conduct live combat trials with new

and upgraded warplanes, testing the aircraft in potentially deadly

conditions before committing to expensive manufacturing programs.

That’s

right. America’s aerial bombing campaigns are also laboratories for the

military and the arms industry. After all, how better to pinpoint an

experimental warplane’s strengths and weaknesses than to send it into an

actual war?

The

twin-engine Broncos—each flown by a pair of naval aviators—completed

134 sorties, including 120 combat missions, over a span of 82 days

beginning in May 2015 or shortly thereafter, according to U.S. Central

Command, which oversees America’s wars in the Middle East and

Afghanistan.

Central Command would not say exactly where the OV-10s were based or where they attacked, but did

specify that the diminutive attack planes with their distinctive twin

tail booms flew in support of Operation Inherent Resolve, the U.S.-led

international campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria. The Pentagon has

deployed warplanes to Turkey, Kuwait, Qatar, Jordan, and the United Arab

Emirates, among other countries.

There

are plenty of clues as to what exactly the Broncos were doing. For one,

the Pentagon’s reluctance to provide many details about the OV-10s’

overseas missions implies that the planes were working in close

conjunction with Special Operations Forces. In all likelihood, the tiny

attackers acted as a kind of quick-reacting 9-1-1 force for special

operators, taking off quickly at the commandos’ request and flying low

to hit elusive militants with guns and rockets, all before the

fleet-flooted jihadis could slip away.

The

military’s goal was “to determine if properly employed turbo-prop

driven aircraft… would increase synergy and improve the coordination

between the aircrew and ground commander,” Air Force Capt. P. Bryant

Davis, a Central Command spokesman, told The Daily Beast.

Davis said that the military also wanted to know if Broncos or similiar planes could take over for jet fighters such as F-15s

and F/A-18s, which conduct most of America’s airstrikes in the Middle

East but are much more expensive to buy and operate than a

propeller-driven plane like the OV-10. An F-15 can cost

as much as $40,000 per flight-hour just for fuel and maintenance. By

contrast, a Bronco can cost as little as $1,000 for an hour of flying.

Indeed,

that was the whole point of the OV-10 when North American Aviation, now

part of Boeing, developed the Bronco way back in the 1960s. The

Pentagon wanted a small, cheap attack plane that could take off from

rough airstrips close to the fighting. By sticking close to the front

lines, the tiny planes would always be available to support ground

troops trying to root out insurgent forces.

The

Bronco turned out to be just the thing the military needed. The Air

Force, Navy, and Marine Corps deployed hundreds of OV-10s in Vietnam,

where the tiny planes proved rugged, reliable, and deadly to the enemy.

After Vietnam, the Navy retired its Broncos and the Air Force swapped

its own copies for jet-powered A-10s, but the Marines hung onto the

dependable little bombers and even flew them from small Navy aircraft

carriers before finally retiring them in the mid-1990s.

Foreign

air forces and civilian and paramilitary operators quickly snatched up

the decommissioned Broncos. They proved popular with firefighting

agencies. The Philippines deployed OV-10s to devastating effect in its

counterinsurgency campaign against Islamic militants. The U.S. State

Department sent Broncos to Colombia to support the War on Drugs. NASA

used them for airborne tests.

Thirty

years after Vietnam, the Pentagon again found itself fighting elusive

insurgents in Afghanistan, Iraq and other war zones. It again turned to

the OV-10 for help. In 2011, Central Command and Special Operations

Command borrowed two former Marine Corps Broncos—from NASA or the State

Department, apparently—and fitted them with new radios and weapons.

The

Defense Department slipped $20 million into its 2012 budget to pay for

the two OV-10s to deploy overseas—part of a wider military experiment

with smaller, cheaper warplanes.

There

was certainly precedent for the experiment going back a decade or more.

During the 1991 Gulf War, the Air Force deployed a prototype E-8 radar

plane to track Iraqi tanks across the desert. The Air Force’s

high-flying Global Hawk spy drone was still just a prototype when the

Air Force sent it overseas to spy on the Taliban and Al Qaeda in late

2001. Satisfied with both aircraft’s wartime trials, the military

ultimately spent billions of dollars buying more of them.

Not to be outdone, in November 2015 Russia sent Tu-160 heavy bombers

to strike targets in Syria—the giant bombers’ very first combat

mission, and one that many observers assumed was really meant as a test

of the planes’ combat capabilities in advance of a planned upgrade

program.

Such

combat experiments don’t always please everyone. When the Pentagon

proposed to spend $20 million on the OV-10s, Sen. John McCain, the

penny-pinching Arizona Republican who now chairs the Senate Armed

Services Committee, objected. “There is no urgent operational

requirement for this type of aircraft,” McCain said

in a statement. Lawmakers subsequently canceled most of the Broncos’

funding, but the military eventually succeeded in paying for the trial

by diverting money from other programs.

The

OV-10s proved incredibly reliable in their 82 days of combat,

completing 99 percent of the missions planned for them, according to

Davis. Today the two OV-10s are sitting idle at a military airfield in

North Carolina while testers crunch the numbers from their trial

deployment. The assessment will “determine if this is a valid concept

that would be effective in the current battlespace,” Central Command

spokesman Davis said.

Lt. Gen. Bradley Heithold, the head of Air Force Special Operations Command, has already hinted

that the military will stick with its current jet fighters for attack

missions. At a February defense-industry conference in Orlando, Heithold

said the OV-10s have “some utility,” but added that it’s too expensive

to pay for training and supplies for a fleet of just two airplanes.

Typically, the Pentagon buys hundreds of planes at a time, partly to

achieve economies of scale.

Yes, the OV-10s are cheaper per plane and per flight than, say, an F-15. But for those savings to matter, the military would need to acquire hundreds of Broncos—not two. And that’s not something that planners are willing to do quite yet.

Which

is not to say the tiny attackers’ combat trial was a failure. To know

for sure whether the Vietnam-veteran OV-10s still had anything to offer,

the military had to send them back to war. And lucky for testers,

there’s still plenty of war going on.

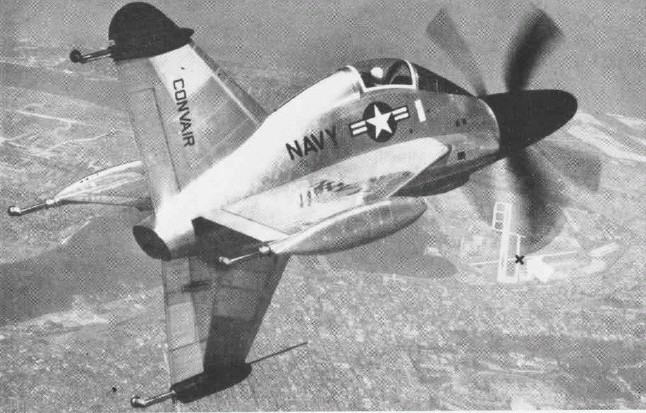

Fastest propeller-driven aircraft

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A number of aircraft have claimed to be the fastest propeller-driven aircraft.

This article presents the current record holders for several

sub-classes of propeller-driven aircraft that hold recognized,

documented speed records. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (FAI) records are the basis for this article.[1]

Other contenders and their claims are discussed, but only those made

under controlled conditions and measured by outside observers. Pilots

during World War II sometimes claimed to have reached supersonic speeds in propeller-driven fighters during emergency dives, but these speeds are not included as accepted records.Propeller versus jet propulsion

Aircraft that use propellers as their prime propulsion device constitute a historically important subset of aircraft, despite inherent limitations to their speed. Aircraft powered by piston engines get virtually all of their thrust from the propeller driven by the engine. A few piston engined aircraft derive some thrust from the engine's exhaust gases, and there are certain hybrid types like the Motorjet that use a piston engine to drive the compressor of a jet engine, which supplies the primary thrust (although some types also have a propeller powered by the piston engine for low speed efficiency). All aircraft prior to World War II (except for a tiny number of early jet aircraft and rocket aircraft) used piston engines to drive propellers, so all Flight airspeed records prior to 1944 were necessarily set by propeller-driven aircraft. Rapid advances in jet engine technology during World War II meant that no propeller-driven aircraft would ever again hold an absolute air speed record. Shock wave formation in propeller-driven aircraft at speeds near sonic conditions, impose limits not encountered in jet aircraft.Jet engines, particularly turbojets, are a type of gas turbine configured such that most of the work available results from the thrust of the hot exhaust gases. High bypass turbofans that are used in all modern commercial jetliners, and most modern military aircraft, get most of their thrust from the internal fan, which is powered by a gas turbine; turboprop engines are similar, but use an external propeller rather than an internal fan. The hot exhaust gas from a turboprop engine can give a small amount of thrust, but the propeller is the main source of thrust.

Turboprops

The Tupolev Tu-114, a large aircraft with four turboprop engines, has a maximum speed of 870 km/h (540 mph, Mach 0.73).[2] The 11,000 kW (15,000 hp) Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprop engines designed for the Tupolev Tu-95 (and used to power the derivative Tu-114) are the most powerful turboprops ever built and drive large contra-rotating propellers. This engine-propeller combination gives the Tu-114 the official distinction of being the fastest propeller-driven aircraft in the world, a record it has held since 1960.[1][3]Probably the fastest aircraft ever fitted with an operating propeller was the experimental McDonnell XF-88B, which was made by installing an Allison T38 turboshaft engine in the nose of a pure jet-powered XF-88 Voodoo. This unusual aircraft was intended to explore the use of high-speed propellers and achieved supersonic speeds.[4] This aircraft is not considered to be propeller-driven since most of the thrust was provided by two jet engines.

An oft-cited contender for the fastest propeller-driven aircraft is the XF-84H Thunderscreech. This aircraft is named in Guinness World Records, 1997, as the fastest in this category with a speed of 1,002 km/h (623 mph, Mach 0.83).[5] While it may have been designed as the fastest propeller-driven aircraft, this goal was not realized due to its inherent instability.[6] This record speed is also inconsistent with data from the National Museum of the United States Air Force, which gives a top speed of 837 km/h (520 mph, Mach 0.70),[7] slower than the Tu-114.

Piston engines

The more "traditional" class of propeller-driven aircraft are those powered by piston engines, which include nearly all aircraft from the Wright brothers up through World War II. Today piston engines are used almost exclusively on light, general aviation aircraft. The official speed record for a piston plane is held by a modified Grumman F8F Bearcat, the Rare Bear, with a speed of 850.24 km/h (528.31 mph) on 21 August 1989 at Las Vegas, Nevada, United States of America.[8][9]The FAI record for the fastest piston-powered aircraft over a long-distance circuit is the 2000-km record of 720.13 km/h (447.47 mph) set on 22 May 1948 by Jacqueline Cochran in a P-51C. (She also holds the 100-km record of 755.67 km/hr, set in December 1947.) Higher speed records exist; some are unofficial and some were officially-timed one-way trips aided by tailwinds. Examples of the latter: a B-29 averaged 725 km/hr from Burbank to Floyd Bennett Field (3957 km in 5.455 hours) on 11 December 1945, and Joe DeBona averaged 904 km/hr from Los Angeles LAX to New York Idlewild (3981 km in 4.405 hours) in a P-51 on 30 March 1954.

Other claimants

The 1903 Wright Flyer did 48 km/h (30 mph) during its first flight; the Bleriot XI reached 75 km/h (47 mph) in 1909. Fabric-covered biplanes of the World War I era and shortly after could do up to 320 km/h (200 mph). In 1925 U.S. Army Lt. Cyrus K. Bettis flying a Curtiss R3C won the Pulitzer Trophy Race with a speed of 400.6 km/h (248.9 mph).[10]Speeds of all-metal monoplanes of the 1930s jumped into the 700 km/h (430 mph) range with the Macchi M.C.72 reaching a top speed of 709 km/h (441 mph), still the record for piston-powered seaplanes.[11] The Messerschmitt Me 209 V1 set a world speed record of almost 756 km/h (470 mph) on 26 April 1939,[12] and the Republic XP-47J (a variant of the P-47 Thunderbolt) is claimed to have reached 813 km/h (505 mph) in testing[citation needed]. A prototype of the successor to the Supermarine Spitfire, the Supermarine Spiteful F.16 (RB518), reached 494 mph (795 km/h). The fastest German propeller driven aircraft to see combat in WWII was the Dornier Do 335 "Pfeil" which had a top speed of 474 mph (763 km/h).[13]

The record-shattering flight, on 2 October 1941, of one of the Messerschmitt Me 163 rocket fighter prototypes that reached a top speed of 624 mph (1,004 km/h), as well as development of jet-powered fighters by both the Allies and Axis powers during World War II, ensured that all new absolute air speed records would be held by jet or rocket-powered aircraft.

During the 1950s two unorthodox United States Navy fighter prototypes married turboprop engines with a "tailsitting design", the Convair XFY "Pogo" and the Lockheed XFV. Maximum design speeds of 980 km/h (610 mph) at 4,600 m (15,100 ft) and 930 km/h (580 mph) respectively have been quoted. The Lockheed XFV was fitted with a less powerful engine than it was designed for and had makeshift non-retractable landing gear for horizontal takeoff and landing;[14] the Convair's landing gear supported it in a vertical position. It was usually flown with the cockpit open, since the ejection seat was thought unreliable.[15] These aircraft had "compromised in-flight speed" because of the conflicting demands of vertical and horizontal flight.[16]

Check Out the Super Tucano Counterinsurgency Fighter Plane In Action

In an era of stealth bombers and super fighters, the U.S. and its allies still have a need for rugged, no-nonsense turboprop fighter planes that harken back to the old days of the P-51 Mustang.The Blaze brings you the A-29 Super Tucano.

In conflict zones around the world, the need for nimble, low-maintenance reconnaissance and light attack capability far outstrips the need for the most advanced 5th generation airframes. The U.S. needs an aerial platform it can give to and train allies on as part of partner building efforts in Afghanistan and other conflict nations.

To meet the demand for counterinsurgency airframes, the U.S. Air Force has awarded Embraer’s Super Tucano a major contract as a Light Air Support (LAS) aircraft, also known as a counterinsurgency (COIN) plane.

The price tag of $355 million for 20 planes is low by combat aviation standards, and the Super Tucano fills a number of aerial defense roles at a tiny fraction of the price of the cost for a modern jet fighter. The U.S. Airforce is buying 20 Super Ts from Embraer and its U.S. partner, Sierra Nevada Corporation.

The Super Tucano will be used to conduct advanced flight training, aerial reconnaissance and light air support combat operations around the world. It is currently in widespread use by Brazil and Colombia, though many more countries have purchased them.

The manufacturer of the Super Tucano, Embraer, described the ideas behind the plane’s design and its evolution over the years as:

“ideally suited to deal with current and future military fight training requirements and also deployable in scenarios that do not fit high-performance combat aircraft…This new multi-purpose military turboprop aircraft embodies features guaranteed to make it as legendary as its predecessor, the Tucano, a favorite of so many air forces throughout the world.”Indeed, earlier versions of the Tucano have been in service for decades. The name Tucano is taken from a town in northeast Brazil, as the company’s founder was Brazilian.

To handle its various roles, Embraer has equipped the A-29 with systems designed not only to comply with basic requirements, but also to keep pace with the continual changes taking place in the aircraft’s potential operating theaters. The Super T’s armaments include:

“Two .50″ machine guns (200 rounds each) in the wings. Five hard points under the wing and fuselage allow up to 1,500 kg of weapons for most configurations…with additional underwing armament, such as two 20mm gun pods or .50″ machine guns, thereby significantly increasing its firepower for missions requiring air-to-ground saturation.”In addition, all weapons stations can be loaded with the Mk 81 or Mk 82 bombs, SBAT-70/19 or LAU-68 rocket launchers. So the Super T has plenty of punch in a small package.

It’s also pretty tough. Crew survivability is ensured through armor protection and state-of-the-art provisions such as a Missile Approach Warning System and Radar Warning Receiver, alongside chaff and flare dispensers.

The Super Tucano’s airframe was designed for single- and twin-seater versions and can withstand +7G/-3.5G loads. The aircraft’s structure is corrosion-protected and the side-hinged canopy has a windshield capable of withstanding a bird strike at 270 kts.

The propulsion system is not especially fancy, but it’s effective. A 1,600 SHP Pratt & Whitney PT6A-68/3 turboprop engine that incorporates FADEC (Full Authority Digital Engine Control) and EICAS (Engine Indication and Crew Alerting System) powers the aircraft.

It does carry some nifty new electronics, and provides a state-of-the art Human-Machine Interface designed to minimize pilot workload and avionics system structured around a MIL-STD-1533 Databus Architecture.

Republic XF-84H

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| XF-84H "Thunderscreech" | |

|---|---|

|

|

| XF-84H serial number 51-17060 in flight | |

| Role | Experimental fighter |

| Manufacturer | Republic Aviation |

| First flight | 22 July 1955 |

| Primary user | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 2 |

| Developed from | Republic F-84F Thunderstreak |

Contents

Design and development

Although the USAF Wright Air Development Center was the key sponsor of the Republic Project 3347 turboprop fighter, the initial inception came from a U.S. Navy requirement for a carrier fighter not requiring catapult assistance.[2] Originally known as XF-106,[3] the project and its resultant prototype aircraft were redesignated XF-84H,[4] closely identifying the program as an F-84 variant, rather than an entirely new type.[5] With a projected contract for three prototypes, when the US Navy cancelled its order, ultimately, the remaining XF-84H prototypes became pure research aircraft built for the Air Force’s Propeller Laboratory at Wright-Patterson AFB to test supersonic propellers in exploring the combination of propeller responsiveness at jet speeds.[6]The XF-84H was created by modifying a F-84F airframe, installing a 5,850 hp (4,360 kW) Allison XT40-A-1 turboprop engine[7] in a centrally-located housing behind the cockpit with a long extension shaft to the nose-mounted propeller.[8] The turbine engine also provided thrust through its exhaust; an afterburner which could further increase power to 7,230 hp (5,391 kW), was installed but never used.[9] Thrust was adjusted by changing the blade pitch of the 12 ft (3.7 m)-diameter Aeroproducts propeller, consisting of three steel, square-tipped blades turning at a constant speed, with the tips traveling at approximately Mach 1.18. To counter the propeller's torque and "P-factor", the XF-84H was fitted with a fixed dorsal yaw vane.[10] The tail was changed to a T-tail to avoid turbulent airflow flow over the horizontal stabilizer/elevator surfaces from propeller wash.[11]

The XF-84H was destabilized by the powerful torque from the propeller, as well as inherent problems with supersonic propeller blades.[12] A number of exotic blade configurations were tested before settling on a final design.[10] Various design features were intended to counteract the massive torque, including mounting the left leading edge intake 12 in (30 cm) further forward than the right, and providing left and right flaps with differential operation.[8] The two prototypes were equally plagued with engine-related problems affecting other aircraft fitted with T40 engines, such as the Douglas XA2D Skyshark and North American A2J Super Savage attack aircraft. A notable feature of the design was that the XF-84H was the first aircraft to carry a retractable/extendable ram air turbine. In the event of engine failure, it would automatically swing out into the airstream to provide hydraulic and electrical power. Due to frequent engine problems, as a precaution, the unit was often deployed in flight.[10]

Testing

After manufacture at Republic's Farmingdale, Long Island, plant, the two XF-84Hs were disassembled and shipped via rail to Edwards Air Force Base for flight testing.[2] The prototypes flew a total of 12 test flights from Edwards, accumulating only 6 hours and 40 minutes of flight time. Lin Hendrix, one of the Republic test pilots assigned to the program, flew the aircraft once and refused to ever fly it again, claiming "it never flew over 450 knots indicated, since at that speed, it developed an unhappy practice of 'snaking', apparently losing longitudinal stability."[13] The other test flights were fraught with engine failures, and persistent hydraulic, nose gear and vibration problems.[2] Test pilot Hank Beaird took the XF-84H up 11 times, with 10 of these flights ending in forced landings.[14]Noise

The XF-84H was quite possibly the loudest aircraft ever built (rivalled only by the Russian Tupolev Tu-95 "Bear" bomber[15]), earning the nickname "Thunderscreech" as well as the "Mighty Ear Banger".[16] On the ground "run ups", the prototypes could reportedly be heard 25 miles (40 km) away.[17] Unlike standard propellers that turn at subsonic speeds, the outer 24–30 inches of the blades on the XF-84H's propeller traveled faster than the speed of sound even at idle thrust, producing a continuous visible sonic boom that radiated laterally from the propellers for hundreds of yards. The shock wave was actually powerful enough to knock a man down; an unfortunate crew chief who was inside a nearby C-47 was severely incapacitated during a 30-minute ground run.[17] Coupled with the already considerable noise from the subsonic aspect of the propeller and the dual turbines, the aircraft was notorious for inducing severe nausea and headaches among ground crews.[11] In one report, a Republic engineer suffered a seizure after close range exposure to the shock waves emanating from a powered-up XF-84H.[18]The pervasive noise also severely disrupted operations in the Edwards AFB control tower by risking vibration damage to sensitive components and forcing air traffic personnel to communicate with the XF-84H's crew on the flight line by light signals. After numerous complaints, the Air Force Flight Test Center directed Republic to tow the aircraft out on Rogers Dry Lake, far from the flight line, before running up its engine.[13] The test program did not proceed further than the manufacturer's Phase I proving flights, consequently no USAF test pilots flew the XF-84H. With the likelihood that the engine and equipment failures coupled with the inability to reach design speeds and subsequent instability experienced were insurmountable problems, the USAF cancelled the program in September 1956.[19]

Historical significance

See also: Fastest propeller-driven aircraft

Operators

Aircraft disposition

Two prototypes were built (51-17059 and 51-17060), with buzz numbers FS-059 and FS-060.[22]- 51-17059 (FS-059) - on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio. It was retired and spent many years mounted on a pole outside Meadows Field Airport, Bakersfield, California, where its propeller turned by the use of an electric motor.[19] In 1992, the gate guardian was taken to the 178th Fighter Wing of the Ohio Air National Guard, whose volunteers spent over 3,000 hours returning the Thunderscreech to display condition.[23]

- 51-17060 (FS-060) - made only four flights, and is assumed to have been scrapped when the project was cancelled in 1956. Its T40 engine was reportedly used to support the Douglas A2D Skyshark flight test program.[24]

Specifications

General characteristics- Crew: 1

- Length: 51 ft 5 in (15.67 m)

- Wingspan: 33 ft 5 in (10.18 m)

- Height: 15 ft 4 in (4.67 m)

- Wing area: 30.75 m ()

- Empty weight: 17,892 lb (8,132 kg)

- Loaded weight: 27,046 lb (12,293 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Allison XT40-A-1 turboprop, 5,850 hp (4,365 kw)

- Maximum speed: 520 mph (837 km/h)

- Range: >2,000 mi (3,200 km)

- Service ceiling: >40,000 ft (14,600 m)

- Rate of climb: 5,000 ft/min (1,520 m/min)

- Thrust/weight: 0.66

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

Douglas A2D Skyshark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| A2D Skyshark | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Role | Attack aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| First flight | March 26, 1950 |

| Status | Cancelled |

| Primary user | United States Navy |

| Number built | 12 (4 never flew) |

| Developed from | A-1 Skyraider |

Contents

Design and development

On 25 June 1945, Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) asked Douglas Aircraft for a turbine-powered, propeller-driven aircraft.[1] Three proposals were put forth in the next year and a half: the D-557A, to use two General Electric TG-100s in wing nacelles; the D-557B, the same engine, with contra-props; and the D-557C, to use the Westinghouse 25D.[1] These were cancelled, due to engine development difficulties, but BuAer continued to seek an answer to thirsty jets.[1]On 11 June 1947,[1] Douglas got the Navy's letter of intent for a carrier-based turboprop. The need to operate from Casablanca-class escort carriers dictated the use of a turboprop instead of jet power.[2] The advantages of turboprop engines over pistons was in power-to-weight ratio and the maximum power that could be generated practically. The advantage over jets was that a turboprop ran at near full RPM all the time, and thrust could be quickly generated by simply changing the propeller pitch.

While resembling the AD Skyraider, the A2D was an entirely different airplane, as it had to be, the Allison XT-40-A2 at 5,100 hp (3,800 kW)[3] having more than double the horsepower of the Skyraider's R3350.[3] Wing root thickness decreased, from 17% to 12%, while both the height of the tail and its area grew.[3] Engine development problems delayed the first flight until 26 May 1950, made at Muroc Air Force Base (renamed Edwards Air Force Base in 1949) by George Jansen.[3]

Test pilot Hugh Wood was killed attempting to land a Skyshark in December 1950. He was unable to check the rate of descent, resulting in a high-impact crash on the runway. (Heinemann, p. 180.)

Allison failed to deliver a "production" engine until 1953, and while testing an XA2D with that engine, test pilot C. G. "Doc" Livingston pulled out of a dive and was surprised by a loud noise and pitch up. His windscreen was covered with oil and the chase pilot told Livingston that the propellers were gone. The gearbox had failed. Livingston successfully landed the airplane.[citation needed] By the summer of 1954, the A4D was ready to fly. The escort carriers were being mothballed, and time had run out for the troubled A2D program.[4]

Due largely to the failure of the T40 program to produce a reliable engine, the Skyshark never entered operational service. Twelve Skysharks were built, two prototypes and 10 pre-production aircraft. Most were scrapped or destroyed in accidents, and only one has survived.[citation needed]

Aircraft on display

- A2D-1 Skyshark, BuNo. 125485, is on display at the airport in Idaho Falls, Idaho. It was restored for static display by Pacific Fighters ca. 1995. [5]

Specifications (XA2D-1)

Data from Encyclopedia of American Aircraft[6]

General characteristics- Crew: 1

- Length: 41 ft 3 in (12.58 m)

- Wingspan: 50 ft 0 in (15.24 m)

- Height: 17 ft 1 in (3.68 m)

- Wing area: 400 ft² (37 m²)

- Empty weight: 12,900 lb (5,864 kg)

- Loaded weight: 18,700 lb (8,500 kg)

- Max. takeoff weight: 22,960 lb (10,436 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Allison XT40-A-2 turboprop, 5,100 shp (3,800 kW)

- Maximum speed: 435 kn (501 mph, 813 km/h)

- Range: 1,900 nmi (2,200 mi, 3,520 km)

- Service ceiling: 48,100 ft (14,664 m)

- Rate of climb: 7,290 ft/min (37 m/s)

- Wing loading: 47 lb/ft² (230 kg/m²)

- Power/mass: 0.27 hp/lb (440 W/kg)

- Guns: 4 × 20 mm (0.79 in) T31 cannon

- Other: 5,500 lb (2,500 kg) on 11 external hardpoints

Tupolev Tu-91

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Tu-91 | |

|---|---|

| Role | Naval attack aircraft |

| National origin | Soviet Union |

| Manufacturer | Tupolev OKB |

| First flight | 17 May 1955 |

| Status | Prototype only |

| Number built | 1 |

Development and design

Following the end of World War II, Stalin ordered an aggressive naval expansion to counter the US naval superiority. It called for building extra warships and a fleet of aircraft carriers. In order to equip the proposed carriers, Soviet Naval Aviation required a long-range carrier-based strike aircraft, capable of attacking with bombs or torpedoes. The Tupolev Design bureau decided on a single-engined turboprop aircraft, designated Tu-91 to meet this requirement.[1]The Tu-91 was a low-winged monoplane with upswept wings. It was powered by an Isotov TV2 engine mounted mid-fuselage and driving a six-bladed Contra-rotating propeller in the nose via a long shaft. The crew of two sat side by side in a cockpit in the aircraft's nose, protected by armour plating. It could carry a heavy load of torpedoes or bombs on pylons under the fuselage and under the wings, and had a gun armament of two cannon in the wing roots and two more in a remotely controlled tail turret.[1]

After the death of Stalin in 1953, the planned fleet of carriers was cancelled, but development of the Tu-91 continued as a land-based aircraft, the design being revised to eliminate wing-folding and arresting gear. It first flew on 17 May 1955,[1] demonstrating excellent performance, resulting in production being authorized. However, after the aircraft was ridiculed by Nikita Khrushchev when inspecting the prototype, the Tu-91 was cancelled.[2]

Specifications (Tu-91)

Data from The Osprey Encyclopedia of Russian Aircraft 1875–1995 [3]

General characteristics- Crew: Two (Pilot and Observer)

- Length: 17.70 m (58 ft 0⅞ in)

- Wingspan: 16.40 m (53 ft 9⅝ in)

- Height: 5.06 m[4] (16 ft 7⅛ in)

- Wing area: 47.5 m² (511 ft²)

- Empty weight: 8,000 kg (17,600 lb)

- Max. takeoff weight: 14,400 kg (31,746 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Isotov TV2M turboprop, 5,709 kW (7,650 shp)

- Propellers: 6 blade Contra-rotating propellers

- Maximum speed: 800 km/h (432 kn, 497 mph)

- Cruise speed: 250–300 km/h (135–162 kn, 155–186 mph)

- Range: 2,350 km (1,270 nmi, 1,460 mi)

- Service ceiling: 11,000 m (36,000 ft)

- Guns:

- Bombs: up to 1,500 kg (3,307 lb) of bombs, rockets or a single torpedo

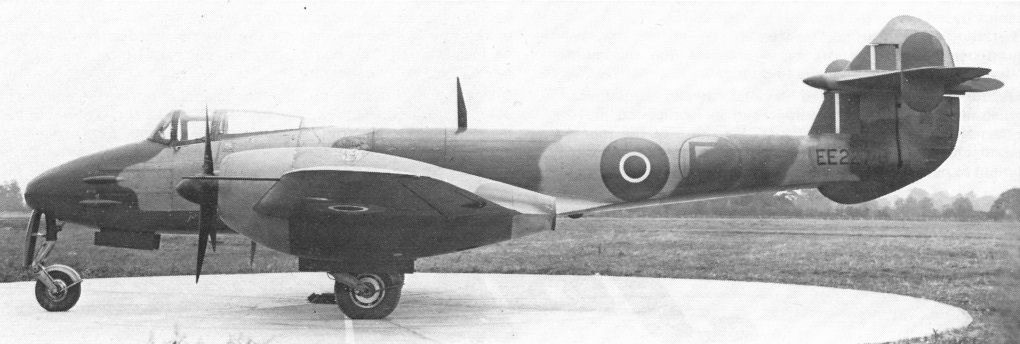

Westland Wyvern

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Wyvern | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Wyvern S.Mk.4 | |

| Role | Carrier-based strike aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Westland Aircraft |

| First flight | 16 December 1946 |

| Introduction | 1953 |

| Retired | 1958 |

| Primary user | Fleet Air Arm |

| Produced | 1946-1956 |

| Number built | 127 |

Contents

Design and development

The Wyvern began as a Westland project for a naval strike fighter, with the engine located behind the pilot, driving a propeller in the nose via a long shaft that passed under the cockpit floor.[1] This enabled the pilot to be located in a position that conferred the best possible visibility over the nose for carrier operations.[1] Official interest resulted in Air Ministry Specification N.11/44 for a long-range naval fighter using the 24-cylinder H-block Rolls-Royce Eagle 22 piston engine (unrelated to the First World War-era engine of the same name) being issued to cover Westland's design.[1] The specification also called for an airframe design that would be able to take a turboprop engine when a suitable unit was available. There was a parallel specification for the Royal Air Force, F.13/44, for which Hawker submitted the competing P.1027, a development of the Tempest. The RAF variant was cancelled, when in 1945 it was decided that all future fighter aircraft would be jet-powered.[1]The prototype W.34; the Wyvern TF Mk 1, first flew at Boscombe Down on 16 December 1946 with Westland's test pilot Harald Penrose at the controls. This aircraft was lost on 15 October 1947 when the propeller bearings failed in flight. Westland's assistant test pilot Sqn. Ldr. Peter Garner was killed attempting to make an emergency landing. From prototype number three onwards, the aircraft were navalised and carried their intended armament.[1]

The first Python-powered TF.2 flew on 22 March 1949 and this aircraft introduced the ejection seat to the Wyvern. Twenty TF.2s were completed to the Python design although after three years of testing what was then a revolutionary aircraft design, a myriad of detailed aerodynamic changes resulted. The Python engine responded poorly to minor throttle adjustments, so control was exercised by running the engine at a constant speed and varying the pitch of the propellers. The aircraft was declared ready for service in 1952,[1] but never reached an operational squadron.[1]

The definitive Wyvern mark was the TF.Mk.4, later S.Mk.4. Initially, 50 Mark 4s were ordered and were joined by the last seven TF.2s, which were altered while still under construction. Mk.4s reached limited shore-based front line service in May 1953 with 813 Naval Air Squadron at RNAS Ford, replacing the somewhat similar (and equally troubled) Blackburn Firebrand. Several second line squadrons also received Wyverns around this time.

Total production was 127 airframes with 124 aircraft completed, as the last three Eagle piston engined airframes, VR138/VR140, were never completed.[3][4]

Operational history

The first carrier trials were carried out by the first pre-production Wyvern TF.2 aboard HMS Illustrious on 21 June 1950.[5] Despite this, when the Wyvern S.4 entered service with 813 Naval Air Squadron in May 1953, it had not obtained clearance for carrier operations, this being obtained only in April 1954.[6] The Wyvern was in service with the Fleet Air Arm from 1954 to 1958. Wyverns equipped 813 Squadron, 827 Squadron, 830 Squadron and 831 Squadron of the Fleet Air Arm.In September 1954, 813 embarked with their Wyverns on HMS Albion for carrier-based service in the Mediterranean. The Wyvern soon showed a worrying habit for flameout on catapult launch; the high G forces resulting in fuel starvation. A number of aircraft were lost off Albion's bows and Lt. B. D. Macfarlane made history when he successfully ejected from under water after his aircraft had ditched on launch and been cut in two by the carrier. 813 did not return to Albion until March 1955 when the problems had been resolved.[1]

830 Sqn. took the Wyvern into combat from HMS Eagle, flying 79 sorties[7] during Operation Musketeer; the armed response to the Suez Crisis. Two Wyverns were lost to damage from Egyptian light anti-aircraft fire; both pilots of the aircraft successfully ejected over the sea, and were picked up by Eagle's search and rescue helicopter. The squadron returned to the UK on Eagle after this conflict and disbanded in January 1957. Consequently, 813 was the last Wyvern squadron, disbanding on 22 April 1958.[1]

All Wyverns were withdrawn from service by 1958: while in service and testing there were 68 accidents, 39 were lost and there were 13 fatalities; including two RAF pilots and one US Navy pilot.

Variants

- W.34 Wyvern

- Six prototypes ordered in August 1944, first aircraft flown 12 December 1946.

- W.34 Wyvern TF. Mk. 1

- Pre-production aircraft ordered in June 1946, only seven built of 20 contracted.

- W.35 Wyvern TF. Mk. 2

- The original production version, three prototypes ordered in February 1946 with a production contract for 20 aircraft ordered in September 1947, only nine production aircraft built, further 11 were completed as S 4s.

- W.38 Wyvern T. Mk. 3

- Two-seat conversion trainer. One prototype VZ739 ordered in September 1948 and first flown in February 1950.

- W.35 Wyvern TF. Mk. 4

- The definitive version, 50 ordered in October 1948, 13 in December 1950, 13 in January 1951 and a final 11 in February 1951, 98 built (including 11 started as TF 2s). Re-designated S. Mk. 4

Survivors

The last remaining Wyvern, a TF.1, externally exhibited at the Fleet Air Arm Museum at RNAS Yeovilton in 1971

Operators

- Fleet Air Arm[8]

- 700 Naval Air Squadron

- 703 Naval Air Squadron

- 764 Naval Air Squadron

- 787 Naval Air Squadron

- 813 Naval Air Squadron

- 827 Naval Air Squadron

- 830 Naval Air Squadron

- 831 Naval Air Squadron

- Wyvern Conversion Unit at Royal Naval Air Station Ford

Specifications (Wyvern S. Mk 4)

Data from Westland Aircraft since 1915[9]

General characteristics- Crew: 1 (2 in T Mk.3)

- Length: 42 ft 3 in (12.88 m)

- Wingspan: 44 ft 0 in (13.41 m) (folded 20 ft (6 m)

- Height: 15 ft 9 in (4.80 m) (folded 20 ft (6 m)

- Wing area: 355 sq ft (33.0 m2)

- Empty weight: 15,600 lb (7,076 kg)

- Gross weight: 21,200 lb (9,616 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 24,550 lb (11,136 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Armstrong Siddeley Python turboprop engine, 3,560 hp (2,650 kW) +1,100 lbf (4.893 kN) residual thrust

- Propellers: 4-bladed Rotol contra-rotating, 13 ft (4.0 m) diameter

- Maximum speed: 383 mph (616 km/h; 333 kn) at sea level, 380 mph (612 km/h) at 10,000 ft (3,048 m)

- Range: 910 mi (791 nmi; 1,465 km)

- Service ceiling: 28,000 ft (8,534 m)

- Rate of climb: 2,350 ft/min (11.9 m/s)

- Wing loading: 59.7 lb/sq ft (291 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.194 eshp/lb

- Guns: 4 × 20mm British Hispano Mk.V cannon, 2 in each wing

- Rockets: 16 × RP-3 underwing rockets

- Missiles: 1 × Mk.15 or Mk.17 torpedo

- Bombs: Up to 3,000 lb (1,361 kg) of bombs or mines

See also

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

Fairey Gannet

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Gannet | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A Royal Navy Fairey Gannet AS.4 | |

| Role | Anti-submarine warfare aircraft |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Fairey Aviation Company |

| Designer | H. E. Chaplin |

| First flight | 19 September 1949 |

| Introduction | 1953 |

| Retired | 15 December 1978[1] |

| Primary users | Royal Navy Royal Australian Navy German Navy Indonesian Navy |

| Produced | 1953–1959 |

| Number built | 303 (Anti-submarine) 45 (Airborne early warning) |

| Variants | Fairey Gannet AEW.3 |

Originally developed to meet the FAA's anti-submarine warfare requirement, the Gannet was later adapted for operations as an electronic countermeasures and carrier onboard delivery aircraft. The Gannet AEW was a variant of the aircraft developed as a carrier-based airborne early warning platform.

Contents

Development

The Gannet was built in response to the 1945 Admiralty requirement GR.17/45, for which prototypes by Fairey (Type Q or Fairey 17, after the requirement) and Blackburn Aircraft (the Blackburn B-54 / B-88) were built.After considering and discounting the Rolls-Royce Tweed[2] turboprop, Fairey selected an engine based on the Armstrong Siddeley Mamba: the Double Mamba[3] (or "Twin Mamba"), basically two Mambas mounted side-by-side and coupled through a common gearbox to coaxial contra-rotating propellers. Power was transmitted from each engine by a torsion shaft which was engaged through a series of sun, planet, epicyclic and spur gears to give a suitable reduction ratio and correct propeller-shaft rotation.[4]

In 1958 the Gannet was selected to replace the Douglas Skyraider in the AEW role. In order to accommodate the systems required, the Gannet underwent a significant redesign that saw a new version of the Double Mamba installed, new radome mounted under the aircraft, the tailfin increased in area, the undercarriage lengthened and the weapons bay removed. A total of 44 aircraft (plus a single prototype) of the AEW.3 version were produced.[citation needed]

Design

The pilot was seated well forward, conferring a good view over the nose for carrier operations,[2] and sat over the Double Mamba engine, directly behind the gearbox and propellers. The second crew member, an aerial observer, was seated under a separate canopy directly behind the pilot. After the prototype, a second observer was included, in his own cockpit over the wing trailing edge. This addition disturbed the airflow over the horizontal stabiliser, requiring small finlets on either side.[6] The Gannet had a large internal weapons bay in the fuselage and a retractable radome under the rear fuselage.The Gannet's wing folded in two places to form a distinctive Z-shape on each side. The first fold was at about a third of the wing length where the inboard anhedral (down-sweep) changed to the outboard dihedral (up-sweep) of the wing (described as a gull wing). The second wing fold was at about two-thirds of the wing length.[7] The length of the nosewheel shock absorber caused the Gannet to have a distinctive nose-high attitude, a common characteristic of carrier aircraft.

In FAA service, the Gannet generally wore the standard camouflage scheme of a Sky (duck-egg blue) underside and fuselage sides, with Extra Dark Sea Grey upper surfaces, the fuselage demarcation line running from the nose behind the propeller spinner in a straight line to then curve and join the line of the fin. Code numbers were typically painted on the side of the fuselage ahead of the wing; roundel and serial markings were behind the wing. The T.2 and T.5 trainers were finished in silver overall, with a yellow "Trainer band" on rear fuselage and wings.[citation needed]

Operational history

The prototype first flew on 19 September 1949 and made the first deck landing by a turboprop aircraft, on HMS Illustrious on 19 June 1950, by pilot Lieutenant Commander G. Callingham. After a further change in operational requirements, with the addition of a radar and extra crew member, the type entered production in 1953 and initial deliveries were made of the variant designated AS.1 at RNAS Ford in April 1954. A trainer variant (T.2) WN365 first flew in August 1954. The RN's first operational Gannet squadron (826 NAS) was embarked on HMS Eagle. The initial order was for 100 AS.1 aircraft. A total of 348 Gannets were built, of which 44 were the heavily modified AEW.3. Production was shared between Fairey's factories at Hayes, Middlesex and Heaton Chapel, Stockport / Manchester (Ringway) Airport.By the mid-1960s, the AS.1s and AS.4s had been replaced by the Westland Whirlwind HAS.7 helicopters. Gannets continued as Electronic countermeasures aircraft: the ECM.6. Some AS.4s were converted to COD.4s for Carrier onboard delivery—the aerial supply of mail and light cargo to the fleet.

The Royal Australian Navy purchased the Gannet AS.1 (36 aircraft). It operated from the aircraft carrier HMAS Melbourne and the shore base HMAS Albatross near Nowra, New South Wales. Indonesia bought a number of AS.4 and T.5s (re-modelled from RN AS.1s and T.2s) in 1959. Some Gannets were later acquired by various other countries.

West Germany bought 15 Gannet AS.4s and one T.5 in 1958. They operated as the anti-submarine squadron of Marinefliegergeschwader 2 (2nd Naval Fighter Wing) from Jagel and Sylt. In 1963 the squadron was reassigned to MFG 3 at Nordholz Naval Airbase until the Gannets were replaced by the Breguet Br.1150 Atlantic in 1966. During its operations the German Navy lost one AS.4, on 12 May 1966, when a Gannet crashed shortly after takeoff from Kaufbeuren, killing all three crew members.

Accidents and mishaps

- 21 November 1958 - Fairey Gannet AS.1, WN345, suffered a belly landing during a test programme, caused by a partially retracted nosewheel. The pilot tried unsuccessfully to get the gear to deploy. He landed gear-up on a foam-covered runway at Bitteswell, suffering minimal damage. After repair, the Gannet was back in the air within weeks.[8]

- 29 July 1959 - Royal Navy Fairey Gannet AS.4, XA465, could not lower the undercarriage, made a power-on deck belly landing into the crash barrier on HMS Centaur. The crew was uninjured but the airframe was written off,[9] salvaged in Singapore, but ending up at the fire dump of Singapore Naval Base.[10]

- 23 January 1964 - Royal Navy Fairey Gannet ECM.6 XG832 suffered double engine failure caused by a phosphor bronze bush on the idler gear of the port engine’s primary accessory drive failing. Fine metal particles from the gear were carried away by the shared oil system of the two engines, causing both to be destroyed. All three crew bailed out near St Austell and survived.[4]

- 12 May 1966 - German Navy AS.4 UA-115 crashed shortly after takeoff from Kaufbeuren, killing all three crew members. The crash was deemed the result of pilot error.[11]

Harness restraint issues

Tests on the harness restraint system in the Gannet were carried out after a midflight failure due to the release cables binding. The accident itself was the result of an unrelated engine failure, but the primary issue was the failure of the harness quick-release mechanism.A brief report in Cockpit, Q4 1973, concerning the accident:

"A Gannet was launched at night from Ark Royal and climbed to 4,000 ft. Shortly afterwards the starboard engine ran down to 60%. Attempts to feather and brake the engine, and a subsequent re-light were unsuccessful and the aircraft was unable to maintain height. (It is considered that the most likely cause of the accident was disconnection of the HP cock linkage). Both observers bailed out at 1,800ft, but when the pilot, Lieutenant Keith Jones, tried to bail out he could not free himself from the 'Negative g' strap. However, the rest of the harness had fallen clear and so the pilot was committed to a ditching without any restraint from shoulder or lap straps. This was successfully accomplished and the aircrew were all recovered safely and uninjured...

Although the ditching was successful, the most disturbing factor of the accident, was the inability of the pilot to release himself from 'Negative g' strap..."[12]

Gannet T.2 advanced trainer demonstrating in 1955 with one-half of the Double Mamba shut down and weapons bay open

Side view comparison of Fairey Gannet ASW and AEW versions

Specifications (Gannet AS.1)

Data from British Naval Aircraft since 1912[22]

General characteristics

Crew: 3

Length: 43ft (13m)

Wingspan: 54ft 4in (16.56m)

Height: 13ft 9in (4.19m)

Wing area: 483 ft² (45 m²)

Empty weight: 15,069 lb (6,835kg)

Powerplant: 1 × Armstrong Siddeley Double Mamba ASMD 1 turboprop, 2,950 hp (2,200kW)

Propellers: 2 contra-rotating 4-bladed

Performance

Maximum speed: 310 mph (500 km/h)

Service ceiling: 25,000 ft (7,600 m)

Endurance: 5-6 hours

Armament

Up to 2,000lb of bombs, torpedoes, depth charges and rockets

Turboprop

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Not to be confused with propfan.

The propeller is coupled to the turbine through a reduction gear that converts the high RPM, low torque output to low RPM, high torque. The propeller itself is normally a constant speed (variable pitch) type similar to that used with larger reciprocating aircraft engines.[citation needed]

Turboprop engines are generally used on small subsonic aircraft, but some aircraft outfitted with turboprops have cruising speeds in excess of 500 kt (926 km/h, 575 mph). Large military and civil aircraft, such as the Lockheed L-188 Electra and the Tupolev Tu-95, have also used turboprop power. The Airbus A400M is powered by four Europrop TP400 engines, which are the third most powerful turboprop engines ever produced, after the Kuznetsov NK-12 and Progress D-27.[citation needed]

In its simplest form a turboprop consists of an intake, compressor, combustor, turbine, and a propelling nozzle. Air is drawn into the intake and compressed by the compressor. Fuel is then added to the compressed air in the combustor, where the fuel-air mixture then combusts. The hot combustion gasses expand through the turbine. Some of the power generated by the turbine is used to drive the compressor. The rest is transmitted through the reduction gearing to the propeller. Further expansion of the gasses occurs in the propelling nozzle, where the gasses exhaust to atmospheric pressure. The propelling nozzle provides a relatively small proportion of the thrust generated by a turboprop.

Turboprops are most efficient at flight speeds below 725 km/h (450 mph; 390 knots) because the jet velocity of the propeller (and exhaust) is relatively low. Due to the high price of turboprop engines, they are mostly used where high-performance short-takeoff and landing (STOL) capability and efficiency at modest flight speeds are required. The most common application of turboprop engines in civilian aviation is in small commuter aircraft, where their greater power and reliability than reciprocating engines offsets their higher initial cost and fuel consumption. Turboprop airliners now operate at near the same speed as small turbofan-powered aircraft but burn two-thirds of the fuel per passenger.[2] However, compared to a turbojet (which can fly at high altitude for enhanced speed and fuel efficiency) a propeller aircraft has a much lower ceiling. Turboprop-powered aircraft have become popular for bush airplanes such as the Cessna Caravan and Quest Kodiak as jet fuel is easier to obtain in remote areas than is aviation-grade gasoline (avgas).[citation needed]

Contents

Technological aspects

Thrust in a turboprop is sacrificed in favor of shaft power, which is obtained by extracting additional power (up to that necessary to drive the compressor) from turbine expansion. While the power turbine may be integral with the gas generator section, many turboprops today feature a free power turbine on a separate coaxial shaft. This enables the propeller to rotate freely, independent of compressor speed. Owing to the additional expansion in the turbine system, the residual energy in the exhaust jet is low. Consequently, the exhaust jet produces (typically) less than 10% of the total thrust.[citation needed]Since propellers are not efficient when their tips reach or exceed supersonic speeds, reduction gearboxes are placed in the drive line between the power turbine and the propeller to allow the turbine to operate at its most efficient speed. The gearbox is part of the engine and contains the parts necessary to operate a constant speed propeller. This differs from the turboshaft engines used in helicopters, where the gearbox is remote from the engine.[citation needed]

Residual thrust on a turboshaft is avoided by further expansion in the turbine system and/or truncating and turning the exhaust 180 degrees, to produce two opposing jets. Apart from the above, there is very little difference between a turboprop and a turboshaft.[citation needed]

While most modern turbojet and turbofan engines use axial-flow compressors, turboprop engines usually contain at least one stage of centrifugal compression. Centrifugal compressors have the advantage of being simple and lightweight, at the expense of a streamlined shape.[citation needed]

Propellers lose efficiency as aircraft speed increases, so turboprops are normally not used on high-speed aircraft. However, propfan engines, which are very similar to turboprop engines, can cruise at flight speeds approaching Mach 0.75. To increase propeller efficiency, a mechanism can be used to alter their pitch relative to the airspeed. A variable pitch propeller, also called a controllable pitch propeller, can also be used to generate negative thrust while decelerating on the runway. Additionally, in the event of an engine outage, the pitch can be adjusted to a vaning pitch (called feathering), thus minimizing the drag of the non-functioning propeller.[citation needed]

Some commercial aircraft with turboprop engines include the Bombardier Dash 8, ATR 42, ATR 72, BAe Jetstream 31, Beechcraft 1900, Embraer EMB 120 Brasilia, Fairchild Swearingen Metroliner, Dornier 328, Saab 340 and 2000, Xian MA60, Xian MA600, and Xian MA700, Fokker 27, 50 and 60.[citation needed]

History

The world's first turboprop was designed by the Hungarian mechanical engineer György Jendrassik.[4] Jendrassik published a turboprop idea in 1928 and on March 12, 1929 he patented his invention. In 1938, he built a small-scale (100 Hp; 74.6 kW) experimental gas turbine.[5] The larger Jendrassik Cs-1, with a predicted output of 1,000 bhp, was produced and tested at the Ganz Works in Budapest between 1937 and 1941. It was of axial-flow design with 15 compressor and 7 turbine stages, annular combustion chamber and many other modern features. First run in 1940, combustion problems limited its output to 400 bhp. In 1941 the factory was turned over to conventional engine production and development ceased.[6]

The first public mention of turboprop engine in a general public press, was in the British aviation publication, Flight, in February 1944 issue, which included a detailed cutaway drawing of what a possible future turboprop engine could look like. The drawing was very close to what the future Rolls-Royce Trent would look like.[7] The first British turboprop engine was the Rolls-Royce RB.50 Trent, a converted Derwent II fitted with reduction gear and a Rotol 7-ft, 11-in five-bladed propeller. Two Trents were fitted to Gloster Meteor EE227 — the sole "Trent-Meteor" — which thus became the world's first turboprop-powered aircraft, albeit a test-bed not intended for production.[8][9] It first flew on 20 September 1945. From their experience with the Trent, Rolls-Royce developed the Rolls-Royce Clyde, the first turboprop engine to be fully type certificated for military and civil use,[10] and the Dart, which became one of the most reliable turboprop engines ever built. Dart production continued for more than fifty years. The Dart-powered Vickers Viscount was the first turboprop aircraft of any kind to go into production and sold in large numbers.[11] It was also the first four-engined turboprop. Its first flight was on 16 July 1948. The world's first single engined turboprop aircraft was the Armstrong Siddeley Mamba-powered Boulton Paul Balliol, which first flew on 24 March 1948.[12]

The Soviet Union built on German World War II development by Junkers (BMW and Hirth/Daimler-Benz also developed and partially tested designs).[citation needed] While the Soviet Union had the technology to create a jet-powered strategic bomber comparable to Boeing's B-52 Stratofortress, they instead produced the Tupolev Tu-95 Bear, powered with four Kuznetsov NK-12 turboprops, mated to eight contra-rotating propellers (two per nacelle) with supersonic tip speeds to achieve maximum cruise speeds in excess of 575 mph, faster than many of the first jet aircraft and comparable to jet cruising speeds for most missions. The Bear would serve as their most successful long-range combat and surveillance aircraft and symbol of Soviet power projection throughout the end of the 20th century. The USA would incorporate contra-rotating turboprop engines, such as the ill-fated Allison T40, into a series of experimental aircraft during the 1950s, but none would be adopted into service.[citation needed]

The first American turboprop engine was the General Electric XT31, first used in the experimental Consolidated Vultee XP-81.[13] The XP-81 first flew in December 1945, the first aircraft to use a combination of turboprop and turbojet power. The technology of the Lockheed Electra airliner was also used in military aircraft, such as the P-3 Orion and the C-130 Hercules, using the Allison T56. One of the most produced turboprop engines is the Pratt & Whitney Canada PT6 engine.[citation needed]

The first turbine-powered, shaft-driven helicopter was the Kaman K-225, a development of Charles Kaman's K-125 synchropter, which used a Boeing T50 turboshaft engine to power it on December 11, 1951.[14]

Propfan

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Aircraft propulsion |

|---|

| Shaft engines: driving propellers, rotors, ducted fans or propfans |

| Reaction engines |

| Others |

Contents

Limitations and solutions

Propeller blade tip speed limit

Turboprops have an optimum speed below about 450 mph (700 km/h).[3] The reason is that all propellers lose efficiency at high speed, due to an effect known as wave drag that occurs just below supersonic speeds. This powerful form of drag has a sudden onset, and led to the concept of a sound barrier when it was first encountered in the 1940s. In the case of a propeller, this effect can happen any time the propeller is spun fast enough that the blade tips near the speed of sound, even if the aircraft is motionless on the ground.The most effective way to counteract this problem (to some degree) is by adding more blades to the propeller, allowing it to deliver more power at a lower rotational speed. This is why many World War II fighter designs started with two or three-blade propellers and by the end of the war were using up to five blades in some cases as the engines were upgraded and new propellers were needed to more efficiently convert that power. The major downside to this approach is that adding blades makes the propeller harder to balance and maintain and the additional blades cause minor performance penalties (due to drag and efficiency issues). But even with these sorts of measures at some point the forward speed of the plane combined with the rotational speed of the propeller will once again result in wave drag problems. For most aircraft this will occur at speeds over about 450 mph (700 km/h).

A method of decreasing wave drag was discovered by German researchers in 1935—sweeping the wing backwards. Today, almost all aircraft designed to fly much above 450 mph (700 km/h) use a swept wing. In the 1970s, Hamilton Standard started researching propellers with similar sweep. Since the inside of the propeller is moving slower than the outside, the blade is progressively more swept toward the outside, leading to a curved shape similar to a scimitar - a practice that was first used as far back as 1909, in the Chauvière make of two-bladed wood propeller used on the Blériot XI.

Jet aircraft fuel economy

Jet aircraft are well known for permitting greater thrusts and higher speeds than could be achieved by conventional propeller-driven aircraft operating within the same aerodynamic envelope. However, jet aircraft are limited in fuel economy. In fact, for the same fuel consumption, a propeller-driven aircraft can produce greater thrust. As fuel costs become an increasingly important aspect of commercial aviation, aircraft engine designers continue to seek an optimal combination of jet engine thrust ratios and propeller fuel efficiency.The propfan concept was developed to deliver 35% better fuel efficiency than contemporary turbofans. In static and air tests on a modified Douglas DC-9, propfans reached a 30% improvement over the OEM turbofans. This efficiency came at a price, as one of the major problems with the propfan is noise, particularly in an era where aircraft are required to comply with increasingly strict aircraft noise regulations. However, in 2012 GE expects that openrotors can meet these noise levels by 2030 when new narrowbody generations from Boeing and Airbus become available. Airlines consistently ask for low noise, and then maximum fuel efficiency.[4]

The Hamilton Standard Division of United Technologies developed the propfan concept in the early 1970s. Numerous design variations of the propfan were tested by Hamilton Standard, in conjunction with NASA in this decade.[5][6] This testing led to the Propfan Test Assessment (PTA) program, where Lockheed-Georgia proposed modifying a Gulfstream II to act as in-flight testbed for the propfan concept and McDonnell Douglas proposed modifying a DC-9 for the same purpose.[7] NASA chose the Lockheed proposal, where the aircraft had a nacelle added to the left wing, containing a 6000 hp Allison 570 turboprop engine (derived from the XT701 turboshaft developed for the Boeing Vertol XCH-62 program), powering a 9-foot diameter Hamilton Standard SR-7 propfan. The aircraft, so configured, first flew in March 1987. After an extensive test program, the modifications were removed from the aircraft.[8][9]

General Electric's GE36 Unducted Fan was a variation on the original propfan concept, and appears similar to a pusher configuration piston engine. GE's UDF has a novel direct drive arrangement, where the reduction gearbox is replaced by a low-speed seven-stage free turbine. The turbine rotors drive the forward set of propellers, while the rear set is connected to the free turbine stators and rotates in the opposite direction. So, in effect, the power turbine has 14 stages. Boeing intended to offer GE's pusher UDF engine on the 7J7 platform, and McDonnell Douglas was going to do likewise on their MD-94X airliner. The GE36 was first flight tested mounted on the #3 engine station of a Boeing 727-100 in 1986.[10]

McDonnell Douglas developed a proof-of-concept aircraft by modifying its company-owned MD-80. They removed the JT8D turbofan engine from the left side of the fuselage and replaced it with the GE36. A number of test flights were conducted, initially out of Mojave, California, which proved the airworthiness, aerodynamic characteristics, and noise signature of the design. Following the initial tests, a first-class cabin was installed inside the aft fuselage and airline executives were offered the opportunity to experience the UDF-powered aircraft first-hand. The test and marketing flights of the GE-outfitted demonstrator aircraft concluded in 1988, exhibiting a 30% reduction in fuel consumption over turbo-fan powered MD-80, full Stage III noise compliance, and low levels of interior noise/vibration. Due to jet fuel price drops and shifting marketing priorities, Douglas shelved the program the following year.

In the 1980s, Allison collaborated with Pratt & Whitney on demonstrating the 578-DX propfan. Unlike the competing GE36 UDF, the 578-DX was fairly conventional, having a reduction gearbox between the LP turbine and the propfan blades. The 578-DX was successfully flight tested on a McDonnell Douglas MD-80. However, none of the above projects came to fruition, mainly because of excessive cabin noise (compared to turbofans) and low fuel prices.[11]

With the current high price for jet fuel and the emphasis on engine/airframe efficiency to reduce emissions, there is renewed interest in the propfan concept for jetliners that might come into service beyond the Boeing 787 and Airbus A350XWB. For instance, Airbus has patented aircraft designs with twin rear-mounted counter-rotating propfans.[12]

Aircraft with propfans

Main category: Propfan-powered aircraft

See also

- Comparable engines

- Europrop TP400

- General Electric GE-36 UDF

- Kuznetsov NK-12

- Rolls-Royce RB3011

- Pratt & Whitney/Allison 578-DX

- Progress D-27

- Metrovick F.5

Piper PA-48 Enforcer

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| PA-48 Enforcer | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Role | Counter-insurgency aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Piper Aircraft |

| First flight | 29 April 1971 |

| Retired | 1984 |

| Status | Experimental |

| Number built | 4 |

| Developed from | North American P-51 Mustang Cavalier Mustang |

Design and development