From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle)

This article is about NASA's new manned spacecraft. For other spaceflight vehicles called Orion, see Orion in astronautics.

|

|

|---|---|

| Description | |

| Role: | Beyond LEO, back-up for commercial cargo and crew to the ISS[1] |

| Crew: | 2–6[2] |

| Carrier rocket: | Space Launch System (planned-deep space),

Delta IV (test flight), Ares I (cancelled) |

| Launch date: | December 2014 (uncrewed test launch)[3][4] |

| Dimensions | |

| Height: | |

| Diameter: | 5 m (16.5 ft) |

| Pressurized volume: | 19.56 m3 (691 cu ft) [5] |

| Habitable volume: | 8.95 m3 (316 cu ft) [5] |

| Capsule mass: | 8,913 kg (19,650 lb) |

| Service Module mass: | 12,337 kg (27,198 lb) |

| Total mass: | 21,250 kg (46,848 lb) |

| Service Module propellant mass: | 7,907 kg (17,433 lb) |

| Performance | |

| Total delta-v: | 1,595 m/s |

| Endurance: | 21.1 days[2][5] |

The MPCV was announced by NASA on May 24, 2011,[9] aided by designs and tests already completed for a spacecraft of the cancelled Constellation program, development for which began in 2005 as the Crew Exploration Vehicle. It was formerly going to be launched by the tested-but-cancelled Ares I launch vehicle.[10]

The MPCV's debut unmanned multi-hour test flight, known as Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1), is scheduled for a launch aboard a Delta IV Heavy rocket in December 2014.[3][4][11] The first crewed mission is expected to take place after 2020.[12] In January 2013, ESA and NASA announced that the Orion Service Module will be built by European space company Astrium for the European Space Agency.[13]

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Contents

Mission

The MPCV is developed for crewed missions to the Moon, to an asteroid, and Mars. It is also a backup vehicle for cargo and crewed missions to the International Space Station. It is intended to be launched by the Space Launch System.[7][14] A modified Advanced Crew Escape Suit is planned to be worn by the crew during the launch and re-entry of the mission.[15]The spacecraft is named for the Orion constellation.[16]

History

On January 14, 2004, U.S. President George W. Bush announced the Orion spacecraft, known then as the Crew Exploration Vehicle (CEV), as part of the Vision for Space Exploration:| “ | Our second goal is to develop and test a new spacecraft, the Crew Exploration Vehicle, by 2008, and to conduct the first manned mission no later than 2014. The Crew Exploration Vehicle will be capable of ferrying astronauts and scientists to the Space Station after the shuttle is retired. But the main purpose of this spacecraft will be to carry astronauts beyond our orbit to other worlds. This will be the first spacecraft of its kind since the Apollo Command Module.[17] | ” |

The name is derived from the constellation of Orion, and was also used on the Apollo 16 Lunar Module that carried astronauts John W. Young and Charlie Duke to the lunar surface in April 1972.

After the replacement of Sean O'Keefe, NASA's procurement schedule and strategy changed, as described above. In July 2004, before he was named NASA administrator, Michael Griffin participated in a study called "Extending Human Presence Into the Solar System"[18] for The Planetary Society, as a co-team leader. The study offers a strategy for carrying out Project Constellation in an affordable and achievable manner. Griffin's actions as administrator supported the goals of the plan.

According to the executive summary, the study was built around "a staged approach to human exploration beyond low Earth orbit (LEO)."[18] It recommends that Project Constellation be carried out in three distinct stages. These are:

- Stage 1 – "Features the development of a new crew exploration vehicle (CEV), the completion of the International Space Station (ISS), and an early retirement of the shuttle orbiter. Orbiter retirement would be made as soon as the ISS U.S. Core is completed (perhaps only 6 or 7 flights) and the smallest number of additional flights necessary to satisfy our international partners' ISS requirements. Money saved by early orbiter retirement would be used to accelerate the CEV development schedule shorten the hiatus in U.S. capability to reach and return from LEO."[18]

- Stage 2 – "Requires the development of additional assets, including an updated CEV capable of extended missions of many months in interplanetary space. Habitation, laboratory, consumables, and propulsion modules, to enable human flight to the vicinities of the Moon and Mars, the Lagrange points, and certain near-Earth asteroids."[18]

- Stage 3 – "Development of human-rated planetary landers is completed in Stage 3, allowing human missions to the surface of the Moon and Mars beginning around 2020."[18]

Orion is Apollo-like, not a lifting body or winged vehicle like the now retired Shuttle. Like the Apollo Command Module, Orion would be attached to a service module for life support and propulsion. It is intended to land in water but past versions had included plans for it to land on land. Landing on the west coast would allow the majority of the reentry path to be flown over the Pacific Ocean rather than populated areas. Orion will have an AVCOAT ablative[20] heat shield that would be discarded after each use.

The Orion spacecraft (CEV) will weigh about 25 tons (23 tonnes), less than the mass of the Apollo Command/Service Module at 33 tons (30 tonnes). The Orion Crew Module will weigh about 9.8 tons (8.9 tonnes), greater than the equivalent Apollo Command Module at 6.4 tons (5.8 tonnes). With a diameter of 16.5 feet (5 metres) as opposed to 12.8 feet (3.9 metres), it will provide 2.5 times greater volume.[21]

Accelerated lunar mission development was slated to start by 2010, once the Shuttle was retired. The Lunar Surface Access Module (LSAM) and heavy-lift boosters were to be developed in parallel and would both be ready for flight by 2018. However, these developments were cancelled in 2010 as part of the Constellation program cancellation.

Design revisions and updates

- July 2006 design revisions

- April 2007 contract revision

- May 2007 design update

- August 2007 design update

2009 Human Space Flight Plans Committee

Rollout of Ares I-X at Kennedy Space Center Launch Complex 39 secured by four bolts on a mobile launcher platform.

Among the parameters to be considered in the course of the review are "crew and mission safety, life-cycle costs, development time, national space industrial base impacts, potential to spur innovation and encourage competition, and the implications and impacts of transitioning from current human space flight systems". The review considered the appropriate amounts of research and development and "complementary robotic activity necessary to support various human space flight activities". It also "explores options for extending International Space Station operations beyond 2016".[28]

2010

On October 11, 2010, with the cancellation of the Constellation Program, the Ares program ended and development of the original Orion vehicle was renamed as the MPCV, planned to be launched on top of an alternative Space Launch System. Following cost overruns and schedule delays caused by insufficient funding, the Obama Administration proposed cancellation of the Constellation program in February 2010 which was signed into law 11 October.[29] However, the Orion spacecraft continued to be developed because it supported new presidential goals.2012

An inflatable seal between the clean room and the Orion space capsule which is superior to the ones used on Apollo and the shuttle was tested on December 3, 2012.[30]Design

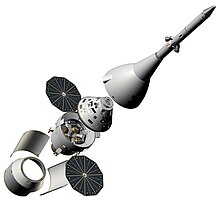

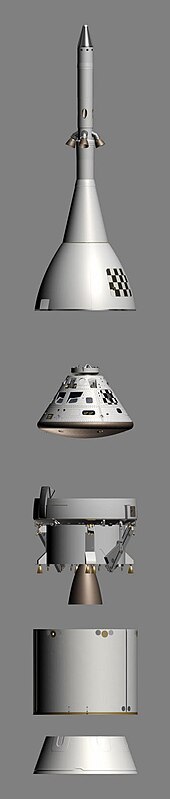

The Orion Crew and Service Module (CSM) stack consists of two main parts: a conical Crew Module (CM), and a cylindrical Service Module (SM) holding the spacecraft's propulsion system and expendable supplies. Both are based substantially on the Apollo Command and Service Modules (Apollo CSM) flown between 1967 and 1975, but include advances derived from the space shuttle program. "Going with known technology and known solutions lowers the risk," according to Neil Woodward, director of the integration office in the Exploration Systems Mission Directorate.[31]The MPCV resembles its Apollo-era predecessors, but its technology and capability are more advanced. It is designed to support long-duration deep space missions of up to 21 days maximum active crew time plus 6 months quiescent.[32] During the quiescent period crew life support would be provided by another module such as a Deep Space Habitat. The spacecraft's life support, propulsion, thermal protection and avionics systems are designed to be upgradeable as new technologies become available.

The MPCV spacecraft includes both crew and service modules, and a spacecraft adaptor.

The MPCV's crew module is larger than Apollo's and can support more crew members for short or long-duration spaceflight missions. The service module fuels and propels the spacecraft as well as storing oxygen and water for astronauts. The service module's structure is also being designed to provide locations to mount scientific experiments and cargo.

Crew Module

The Orion CM will hold four crew members, compared to a maximum of three in the smaller Apollo CM or seven in the larger space shuttle. Despite its conceptual resemblance to the 1960s-era Apollo, Orion's CM will use several improved technologies, including:- "Glass cockpit" digital control systems derived from that of the Boeing 787.[33]

- An "autodock" feature, like those of Russian Progress spacecraft and the European Automated Transfer Vehicle, with provision for the flight crew to take over in an emergency. Previous American spacecraft (Gemini, Apollo, and Space Shuttle) have all required manual piloting for docking.

- Improved waste-management facilities, with a miniature camping-style toilet and the unisex "relief tube" used on the space shuttle (whose system was based on that used on Skylab) and the International Space Station (based on the Soyuz, Salyut, and Mir systems). This eliminates the use of the much-hated plastic "Apollo bags" used by the Apollo crews.

- A nitrogen/oxygen (N

2/O

2) mixed atmosphere at either sea level (101.3 kPa or 14.69 psi) or slightly reduced (55.2 to 70.3 kPa or 8.01 to 10.20 psi) pressure. - Much more advanced computers than on previous manned spacecraft.

To allow Orion to mate with other vehicles it will be equipped with the NASA Docking System, which is somewhat similar to the APAS-95 docking mechanism used on the Shuttle fleet. Both the spacecraft and docking adapter will employ a Launch Escape System (LES) like that used in Mercury and Apollo, along with an Apollo-derived "Boost Protective Cover" (made of fiberglass), to protect the Orion CM from aerodynamic and impact stresses during the first 2 1⁄2 minutes of ascent.

The Orion Crew Module (CM) is a 57.5° frustum shape, similar to that of the Apollo Command Module. As projected, the CM will be 5.02 meters (16 ft 6 in) in diameter and 3.3 meters (10 ft 10 in) in length,[35] with a mass of about 8.5 metric tons (19,000 lb). It is to be built by the Lockheed Martin Corporation.[36] It will have more than 50% more volume than the Apollo capsule, which had an interior volume of 5.9 m3 (210 cu ft), and will carry four to six astronauts.[37] After extensive study, NASA has selected the Avcoat ablator system for the Orion crew module. Avcoat, which is composed of silica fibers with a resin in a honeycomb made of fiberglass and phenolic resin, was previously used on the Apollo missions and on select areas of the space shuttle for early flights.[38]

The crew module is the transportation capsule that provides a habitat for the crew, provides storage for consumables and research instruments, and serves as the docking port for crew transfers. The crew module is the only part of the MPCV that returns to Earth after each mission.

The crew module will have 316 cubic feet (8.9 m3) and capabilities of carrying four astronauts for 21 day flights itself which could be expanded through additional service modules.[39] Its designers claim that the MPCV is designed to be 10 times safer during ascent and reentry than the Space Shuttle.[14]

-

Orion ground test article in Colorado on May 13, 2011.

-

The Orion MPCV ground test vehicle is lifted into the acoustic chamber at Lockheed Martin's facilities near Denver in preparation for the Launch Abort Vehicle Configuration Test.

Service Module

Main article: Orion Service Module

Edoardo Amaldi ATV approaches the International Space Station

ATV-based Service module

On November 21, 2012, the ESA decided they will construct an ATV derived Service Module ready to support the Orion capsule on the maiden flight of the Space Launch System in 2017.[43] The service module will likely be manufactured by EADS Astrium in Bremen, Germany.[44]

| "ESA's contribution is going to be critical to the success of Orion's 2017 mission" |

| —NASA Orion Program manager[13] |

Launch Abort System

See also: Orion abort modes

In the event of an emergency on the launch pad or during ascent, a launch escape system called the Launch Abort System (LAS) will separate the Crew Module from the launch vehicle using a solid rocket-powered launch abort motor (AM), which is more powerful than the Atlas 109-D booster that launched astronaut John Glenn into orbit in 1962.[45]

There are two other propulsion systems in the LAS stack: the attitude

control motor (ACM) and the jettison motor (JM). On July 10, 2007, Orbital Sciences, the prime contractor for the LAS, awarded Alliant Techsystems

(ATK) a $62.5 million sub-contract to, "design, develop, produce, test

and deliver the launch abort motor." ATK, which had the prime contract

for the first stage of the Ares I rocket, intended to use an innovative "reverse flow" design for the motor.[46] On July 9, 2008, NASA announced that ATK had completed a vertical test stand at a facility in Promontory, Utah to test launch abort motors for the Orion spacecraft.[47] Another long-time space motor contractor, Aerojet,

was awarded the jettison motor design and development contract for the

LAS. As of September 2008, Aerojet has, along with team members Orbital

Sciences, Lockheed Martin and NASA, successfully demonstrated two

full-scale test firings of the jettison motor. This motor is important

to every flight in that it functions to pull the LAS tower away from the

vehicle after a successful launch. The motor also functions in the same

manner for an abort scenario.Testing

Environmental testing

NASA performed environmental testing of Orion from 2007 to 2011 at the Glenn Research Center Plum Brook Station in Sandusky, Ohio. The Center's Space Power Facility is the world's largest thermal vacuum chamber.[48]Pathfinder

On March 2, 2009, the LAS Pathfinder began its transfer from the Langley Research Center to the White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico, for launch tests. The Pathfinder is a combination of the Orion Boilerplate and LAS module. The 45 ft (14 m)-long rocket assembly will begin its first Pad Abort 1 Test on the Missile Range.[49]Abort flight testing

Test-firing of Orion LAS jettison motor (shock diamonds are clearly visible in the exhaust plumes)

| This article's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (January 2013) |

Test plans

As of 2007, NASA planned to perform a series of six Abort Flight Tests (AFT) between the fall of 2008 and the end of 2011 at the United States Army's White Sands Missile Range (WSMR), New Mexico.[dated info] The Orion AFT subproject includes two pad abort tests and four ascent abort tests. Three of the four ascent aborts are planned to be flown from a special test launch vehicle, the Orion Abort Test Booster, the fourth one being performed with Ares I-Y. The Orion Abort Flight Tests are similar in nature to the Little Joe II tests performed at WSMR between September 1963 and January 1966 in support of the development of the Apollo program's Launch Escape System.[50][51][52] The LAS Pathfinder[clarification needed] boilerplate is being used.[citation needed]As of February 2014, NASA plans to launch the Orion Multi Purpose Crew Vehicle Ascent Abort 2 test flight (AA‑2) from Spaceport Florida Launch Complex 46 in 2018.[53]

Actual testing

The actual Orion testing accomplished to date has been rather more limited and is running well behind the original plans.ATK successfully completed the first Orion launch-abort test on November 20, 2008. The abort motor will provide 500,000 lbf (2,200 kN) of thrust for an emergency on the launch pad or during the first 300,000 feet (91 km) of the rocket's climb to orbit. The test firing was the first time a motor with reverse flow propulsion technology at this scale has been tested.

This abort test firing brought together a series of motor and component tests conducted in 2008 as a preparation for the next major milestone, a full-size mock-up or boilerplate test scheduled for the spring of 2009.[54][dated info]

On May 10, 2010, NASA successfully executed the PAD-Abort-1 test at White Sands New Mexico, launching a boilerplate Orion capsule to an altitude of approximately 6000 feet. The test used three solid-fuel rocket motors – a main thrust motor, an attitude control motor and the jettison motor.[55]

Orion Recovery Testing

| This section is outdated. (September 2013) |

The Port Test used full-scale boilerplate of NASA's Orion crew module and will be tested in water under simulated and real weather conditions. Tests began March 23, 2009 with a Navy-built, 18,000-pound boilerplate when it was placed in a test pool at the Naval Surface Warfare Center's Carderock Division in West Bethesda, Md. Full sea testing ran April 6–30, 2009, at various locations off the coast of NASA's Kennedy Space Center with media coverage.[56]

Under the Orion program testing a series of tests was implemented to evaluate hardware and procedures used to recover the Orion Crew Module at the end of the mission. Orion continued the "crawl, walk, run" approach used in PORT testing. The "crawl" phase was performed August 12–16, 2013 with the Stationary Recovery Test (SRT).

The SRT demonstrated the recovery hardware and techniques that will be employed for the recovery of the Orion Crew Module in the protected waters of Naval Station Norfolk utilizing the USS ARLINGTON as the recovery ship. The USS ARLINGTON is a LPD 17 Amphibious Assault ship. The recovery of the Orion Crew Module utilizes unique features of the LPD 17 class ship to safely and economically recovery the Orion Crew Module and eventually its astronaut crew.[57]

The "walk" and "run" phases will be performed with the Underway Recovery Test (URT). Also Utilizing the LPD 17 class ship, the URT will be performed in more realistic sea conditions off the coast of California in early 2014 to prepare the US Navy / NASA team for recovering the uncrewed Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1) Orion Crew Module.

Missions

List only includes relatively near missions, more missions are planned than are listed below.| Acronym | Mission name | Launch Date | Rocket | Duration | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EFT-1 | Exploration Flight Test-1 | 2014 | Delta IV Heavy | Uncrewed high apogee trajectory test flight of the Orion Crew Module in Earth Orbit. | |

| EM-1 | Exploration Mission-1[58] | 2017[58] | SLS Block I[58] | 7–10 days[59] | Send an uncrewed Orion on a circumlunar trajectory.[59] |

| EM-2 | Exploration Mission-2[58] | As early as 2021[60] | SLS Block I[58] | Send Orion with a crew of two to rendezvous with a captured asteroid in lunar orbit.[60] | |

| EM-3 | Exploration Mission-3[58] | 2022[61] | SLS Block IA[58] | Destination TBA[61] |

Existing craft and mockups

- The Boilerplate Test Article (BTA) underwent splashdown testing at the Hydro Impact Basin of NASA's Langley Research Center. This same test article has been modified to support Orion Recovery Testing in the Stationary and Underway recovery tests.[62] The BTA contains over 150 sensors to gather data on its test drops.[63] Testing of the 18,000 pound mockup ran from July 2011 to January 6, 2012.[64]

- The Ground Test Article (GTA) stack, located at Lockheed Martin in Denver, is undergoing vibration testing.[65] It is made up by the Orion Ground Test Vehicle (GTV) combined with its Launch Abort System (LAS). Further testing will see the addition of Service Module simulator panels and Thermal Protection System (TPS) to the GTA stack.[66]

- The Drop Test Article (DTA), also known as the Drop Test Vehicle (DTV) is undergoing test drops at the US Army's Yuma Proving Ground in Arizona. The mock Orion parachute compartment is dropped from an altitude of 25,000 feet from a C-130.[66] Testing began in 2007. Drogue chutes deploy around 15,000 and 20,000 feet. Testing of the reefing staged parachutes includes partial failure instances including partial opening and complete failure of one of the three main parachutes. With only two chutes deployed the DTA lands at 33 feet per second, the maximum touchdown speed for Orion's design.[67] Other related test vehicles include the now-defunct Orion Parachute Test Vehicle (PTV) and its replacement the Generation II Parachute Test Vehicle (PTV2). The drop test program has had several failures in 2007, 2008, and 2010.[68] The new PTV was successfully tested February 29, 2012 deploying from a C-17. Ten drag chutes will drag the mock up's pallet from the aircraft for the drop at 25,000 feet. The landing parachute set of eight is known as the Capsule Parachute Assembly System (CPAS).[69] The test examined air flow disturbance behind the mimicked full size vehicle and its effects on the parachute system. The PTV landed on the desert floor at 17 mph.[70] A third test vehicle, the PCDTV3, is scheduled for a drop on April 17, 2012. In this testing "The CPAS team continued preparation activities for the Parachute Compartment Drop Test Vehicle (PCDTV3) airdrop test, scheduled for April 17, which will deploy the two drogue parachutes in the highest dynamic pressure environment to date, and will demonstrate a main parachute skipped second stage."[71]

- Exploration Flight Test 1 (EFT-1) Orion (re-designation of OFT-1) constructed at Michoud Assembly Facility,[72] was delivered by Lockheed Martin to the Kennedy Space Center on July 2, 2012.[73]

Ongoing debates over EM-3 and beyond

Debates over Orion's destination in the near future are ongoing.[74][75] In particular, the United States House Science Subcommittee on Space is exploring the merits of an Apollo-like return to the Moon as compared with an asteroid rendezvous mission.[74]The crux of ongoing debates hinges upon answers to these following questions:[74]

- Is the proposed Asteroid Retrieval Mission (ARM), a lunar landing mission, or another mission better as a precursor for an eventual human mission to Mars?

- What things could we learn and capabilities would we develop from a Moon landing that we could not learn from the proposed Asteroid Retrieval Mission?

- How do different destinations or missions affect a strategic approach with our potential international partners as well as technical architectures?

- return to the Moon or

- explore an asteroid towed to lunar orbit

Regardless of which of the following alternatives is selected, "the ultimate goal of human exploration is to chart a path for human expansion into the solar system."[74]

Return to the Moon

These are the primary reasons for returning to the Moon:[74]- "On the international front, there appears to be continued enthusiasm for a mission to the Moon."[76]

- The Moon could become a training ground and test bed to prepare for more complex missions.[74] Ultimately, manned operations on other planets will require training and preparation. The Moon seems like a logical place to do this training.[74]

- Landing on the Moon would develop technical capabilities that NASA has not had experience with for over four decades now.[74][A] NASA has neither landed humans upon nor launched humans from another large celestial body since December 1972.[A]

- Establishing a semi-permanent or permanent presence on the Moon would provide humans with some working/living experience in radically different, non-Earth environments. Projects Mercury and Gemini built up experience for Apollo's subsequent success to the Moon; in much the same way returning to the Moon would provide experience prior to exploring Mars.[74]

- The Apollo program was not a straight shot to the Moon; it included several precursor missions to test new capabilities and gain experience.[74] In much the same way, NASA will need to acquire new capabilities to travel to Mars and beyond.[74]

- The United States National Research Council reports (December 2012) there is "little evidence that a current stated goal for NASA's human spaceflight program – namely, to visit an asteroid by 2025 – has been widely accepted as a compelling destination by NASA's own workforce, by the nation as a whole, or by the international community."[74][76]

- Legal dictates to utilize the Moon[74] prior to exploring beyond[74] are still in place[74] and contained within the NASA Authorization Acts of 2005 and 2008 (October 16, 2008).[74][77]

Explore an asteroid in lunar orbit

The reasons provided for exploring an asteroid, as follows, versus returning to the Moon, above, appear to revolve around reduced cost[B] and technical advancement:[C]- This mission would place an asteroid in lunar orbit, rather than sending astronauts to an asteroid in deep space.[74]

- The Keck Institute for Space Studies at the California Institute of Technology, in partnership with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, estimates a mission cost of approximately $2.6 billion.[74][78] By contrast, original estimates for colonization of the Moon, as a part of the Constellation Program, reached a total cost of $150 billion.[79] However, the $2.6 billion estimate is solely the cost of a mission to capture a 7m asteroid. It does not include any developmental costs, nor does it cover the costs of crewed flights to the asteroid once it is captured, so this comparison does not include the full costs of this enterprise.[78]

- The Obama Administration estimates that this mission would actually cost even less than the estimated $2.6 billion[74] and is already a part of the FY2014 budget request.[74]

- Steps toward accomplishing this mission would simultaneously develop advanced solar electric propulsion technology.[74]

Orion Lite

Main article: Orion Lite

Orion Lite was an unofficial name used in the media for a lightweight crew capsule proposed by Bigelow Aerospace in collaboration with Lockheed Martin. It was to be based on the Orion spacecraft that Lockheed Martin was developing for NASA. It would be a lighter, less capable and cheaper version of the full Orion.See also

MPCV Related:- Space Shuttle successors

- NASA Authorization Act of 2010

- Space policy of the Barack Obama administration

- Crew Exploration Vehicle (previous version of Orion)

- Mission to a Near-Earth object

- Exploration of Mars

- Manned mission to Mars

- Space Launch System

- Space Exploration Vehicle

- Deep Space Habitat

- Nautilus-X (not currently funded)

- Skylab Rescue

- CST-100 crew capsule being developed by Boeing and Bigelow Aerospace

- Dragon being developed by Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX)

- Dream Chaser being developed by Sierra Nevada Corporation

- Simply known as the "Space Vehicle", a "biconic nose cone design orbital vehicle" orbital spacecraft being developed by Blue Origin... not to be confused with the Blue Origin New Shepard "vertical-takeoff, vertical-landing (VTVL), suborbital manned rocket" also being developed by the same company.[80][81]

- Liberty (formally Ares 1) being developed by Alliant Techsystems and Astrium

- Cygnus being developed by Orbital Sciences Corporation and Thales Alenia Space

- Dragon (uncrewed variant) developed by Space Exploration Technologies (SpaceX)

- Soyuz (spacecraft) and Progress (spacecraft) used by the Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA)

- Prospective Piloted Transport System (PPTS) or Advanced Crew Vehicle (ACV) (to be launched on an Angara A5 rocket)[82] in development by the Russian Federal Space Agency (RKA)

- Shenzhou (spacecraft) used by the China National Space Administration (CNSA)

- ISRO Orbital Vehicle developed by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO)

- Automated Transfer Vehicle used by the European Space Agency (ESA)

- Crew Space Transportation System (CSTS) or Advanced Crew Transportation System (ACTS) in development by the European Space Agency (ESA)

- H-II Transfer Vehicle used by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA)

No comments:

Post a Comment