From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

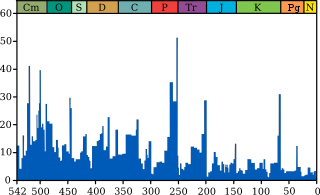

The blue graph shows the apparent percentage (not the absolute number) of marine animal genera

becoming extinct during any given time interval. It does not represent

all marine species, just those that are readily fossilized. The labels

of the "Big Five" extinction events are clickable hyperlinks; see Extinction event for more details. (source and image info)

Over 98% of documented species are now extinct,[2] but extinction occurs at an uneven rate. Based on the fossil record, the background rate of extinctions on Earth is about two to five taxonomic families of marine invertebrates and vertebrates every million years. Marine fossils are mostly used to measure extinction rates because of their superior fossil record and stratigraphic range compared to land organisms.

Since life began on Earth, several major mass extinctions have significantly exceeded the background extinction rate. The most recent, the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, which occurred approximately 66 million years ago (Ma), was a large-scale mass extinction of animal and plant species in a geologically short period of time. In the past 540 million years there have been five major events when over 50% of animal species died. Mass extinctions seem to be a Phanerozoic phenomenon, with extinction rates low before large complex organisms arose.[3]

Estimates of the number of major mass extinctions in the last 540 million years range from as few as five to more than twenty. These differences stem from the threshold chosen for describing an extinction event as "major", and the data chosen to measure past diversity.

Effects and recovery

The impact of mass extinction events varied widely. After a major extinction event, usually only weedy species survive due to their ability to live in diverse habitats.[69] Later, species diversify and occupy empty niches. Generally, biodiversity recovers 5 to 10 million years after the extinction event. In the most severe mass extinctions it may take 15 to 30 million years.[69]The worst event, the Permian–Triassic extinction event, devastated life on earth and is estimated to have killed off over 90% of species. Life seemed to recover quickly after the P-T extinction, but this was mostly in the form of disaster taxa, such as the hardy Lystrosaurus. The most recent research indicates that the specialized animals that formed complex ecosystems, with high biodiversity, complex food webs and a variety of niches, took much longer to recover. It is thought that this long recovery was due to the successive waves of extinction which inhibited recovery, as well as to prolonged environmental stress to organisms which continued into the Early Triassic. Recent research indicates that recovery did not begin until the start of the mid-Triassic, 4M to 6M years after the extinction;[70] and some writers estimate that the recovery was not complete until 30M years after the P-Tr extinction, i.e. in the late Triassic.[71] Subsequent to the PT mass extinction, there was an increase in provincialization, with species occupying smaller ranges - perhaps removing incumbents from niches and setting the stage for an eventual rediversification.[72]

The effects of mass extinctions on plants are somewhat harder to quantify, given the biases inherent in the plant fossil record. Some mass extinctions (such as the end-Permian) were equally catastrophic for plants, whereas others, such as the end-Devonian, did not affect the flora.[73]

No comments:

Post a Comment