Power-to-weight ratio (or

specific power or

power-to-mass ratio) is a calculation commonly applied to

engines

and mobile power sources to enable the comparison of one unit or design

to another. Power-to-weight ratio is a measurement of actual

performance of any engine or power sources. It is also used as a

measurement of performance of a

vehicle as a whole, with the engine's

power output being divided by the weight (or

mass)

of the vehicle, to give a metric that is independent of the vehicle's

size. Power-to-weight is often quoted by manufacturers at the peak

value, but the actual value may vary in use and variations will affect

performance.

The inverse of power-to-weight, weight-to-power ratio (power loading)

is a calculation commonly applied to aircraft, cars, and vehicles in

general, to enable the comparison of one vehicle performance to another.

Power-to-weight ratio is equal to powered

acceleration multiplied by the velocity of any vehicle.

Power-to-weight (specific power)

The power-to-weight ratio (Specific Power) formula for an engine (power plant) is the

power

generated by the engine divided by the mass. ("Weight" in this context

is a colloquial term for "mass". To see this, note that what an engineer

means by the "power to weight ratio" of an electric motor is not

infinite in a zero gravity environment.)

A typical turbocharged V8 diesel engine might have an engine power of 330 horsepower (250 kW) and a mass of 835 pounds (379 kg),

[1] giving it a power-to-weight ratio of 0.65 kW/kg (0.40 hp/lb).

Examples of high power-to-weight ratios can often be found in

turbines. This is because of their ability to operate at very high

speeds. For example, the

Space Shuttle's main engines used

turbopumps (machines consisting of a pump driven by a turbine engine) to feed the propellants (liquid oxygen and

liquid hydrogen)

into the engine's combustion chamber. The original liquid hydrogen

turbopump is similar in size to an automobile engine (weighing

approximately 775 pounds (352 kg)) and produces 72,000

hp (53.6

MW)

[2] for a power-to-weight ratio of 153 kW/kg (93 hp/lb).

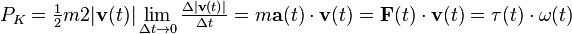

Physical interpretation

In

classical mechanics, instantaneous

power is the limiting value of the average work done per unit time as the time interval Δ

t approaches zero.

The typically used metrical unit of the power-to-weight ratio is

which equals

. This fact allows one to express the power-to-weight ratio purely by

SI base units.

Propulsive power

If the work to be done is

rectilinear motion of a body with constant

mass

, whose

center of mass is to be accelerated along a

straight line to a speed

and angle

with respect to the centre and

radial of a

gravitational field by an onboard

powerplant, then the associated

kinetic energy to be delivered to the body is equal to

where:

is mass of the body

is mass of the body is speed of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is speed of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

The instantaneous mechanical pushing/pulling power delivered to the body from the powerplant is then

where:

is acceleration of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is acceleration of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is linear force - or thrust - applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is linear force - or thrust - applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is torque applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is torque applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is angular velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is angular velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

In propulsion, power is only delivered if the powerplant is in

motion, and is transmitted to cause the body to be in motion. It is

typically assumed here that mechanical transmission allows the

powerplant to operate at peak output power. This assumption allows

engine tuning to trade

power band width and engine mass for transmission complexity and mass.

Electric motors do not suffer from this tradeoff, instead trading their high

torque for

traction at low speed. The

power advantage or

power-to-weight ratio is then

where:

is linear speed of the center of mass of the body.

is linear speed of the center of mass of the body.

Engine power

The actual useful power of any traction engine can be calculated using a

dynamometer to measure

torque and

rotational speed, with peak power sustained when transmission and/or operator keeps the

product

of torque and rotational speed maximised. For jet engines there is

often a cruise speed and power can be usefully calculated there, for

rockets there is typically no cruise speed, so it is less meaningful.

Peak power of a traction engine occurs at a rotational speed higher

than the speed when torque is maximised and at or below the maximum

rated rotational speed - Max RPM. A rapidly falling torque curve would

correspond with sharp torque and power curve peaks around their maxima

at similar rotational speed, for example a small, lightweight engine

with a large turbocharger. A slowing falling or near flat torque curve

would correspond with a slowly rising power curve up to a maximum at a

rotational speed close to Max RPM, for example a large, heavy

multi-cylinder engine suitable for cargo/hauling. A falling torque curve

could correspond with a near flat power curve across rotational speeds

for smooth handling at different vehicle speeds.

Examples

Engines

Heat engines and heat pumps

Thermal energy is made up from

molecular kinetic energy and

latent phase energy.

Heat engines

are able to convert thermal energy in the form of a temperature

gradient between a hot source and a cold sink into other desirable

mechanical work.

Heat pumps take

mechanical work

to regenerate thermal energy in a temperature gradient. Care should be

made when interpreting propulsive power, especially for jet engines and

rockets, deliverable from heat engines to a vehicle.

| Heat Engine/Heat pump type |

Peak Power Output |

Power-to-weight ratio |

Example Use |

| Wärtsilä RTA96-C 14-cylinder two-stroke Turbo Diesel engine[3] |

80,080 kW |

108,920 hp |

0.03 kW/kg |

0.02 hp/lb |

Emma Mærsk container ship |

| Suzuki 538 cc V2 4-stroke gas (petrol) outboard Otto engine[4] |

19 kW |

25 hp |

0.27 kW/kg |

0.16 hp/lb |

Runabout boats |

| DOE/NASA/0032-28 Mod 2 502 cc gas (petrol) Stirling engine[5] |

62.3 kW |

83.5 hp |

0.30 kW/kg |

0.18 hp/lb |

Chevrolet Celebrity[•] 1985 |

| GM 6.6 L Duramax LMM (LYE option) V8 Turbo Diesel engine[1] |

246 kW |

330 hp |

0.65 kW/kg |

0.40 hp/lb |

Chevrolet Kodiak[•], GMC Topkick[•] |

| Junkers Jumo 205A opposed-piston two-stroke Diesel engine[6] |

647 kW |

867 hp |

1.1 kW/kg |

0.66 hp/lb |

Ju 86C-1 airliner, B&V Ha 139 floatplane |

| GE LM2500+ marine turboshaft Brayton gas turbine[7] |

30,200 kW |

40,500 hp |

1.31 kW/kg |

0.80 hp/lb |

GTS Millennium cruiseship, QM2 ocean liner |

| Mazda 13B-MSP Renesis 1.3 L Wankel engine[8] |

184 kW |

247 hp |

1.5 kW/kg |

0.92 hp/lb |

Mazda RX-8[•] |

| PW R-4360 71.5 L 28-cylinder supercharged Radial engine |

3,210 kW |

4,300 hp |

1.83 kW/kg |

1.11 hp/lb |

B-50 Superfortress, Convair B-36 |

| C-97 Stratofreighter, C-119 Flying Boxcar |

| Hughes H-4 Hercules "Spruce Goose" |

| Wright R-3350 54.57 L 18-c s/c Turbo-compound Radial engine |

2,535 kW |

3,400 hp |

2.09 kW/kg |

1.27 hp/lb |

B-29 Superfortress, Douglas DC-7 |

| C-97 S/f prototype, Kaiser-Frazer C-119F |

| O.S. Engines 49-PI Type II 4.97 cc UAV Wankel engine[9] |

0.934 kW |

1.252 hp |

2.8 kW/kg |

1.7 hp/lb |

Model aircraft, Radio-controlled aircraft |

| GE LM6000 marine turboshaft Brayton gas turbine[10][11][disputed – discuss] |

44,700 kW |

59,900 hp |

5.67 kW/kg |

3.38 hp/lb |

Peaking power plant |

| GE CF6-80C2 Brayton high-bypass turbofan jet engine[11] |

Boeing 747[•], 767, Airbus A300 |

| BMW V10 3L P84/5 2005 gas (petrol) Otto engine[12] |

690 kW |

925 hp |

7.5 kW/kg |

4.6 hp/lb |

Williams FW27 car[•], Formula One auto racing |

| GE90-115B Brayton turbofan jet engine[13][14][disputed – discuss] |

83,164 kW |

111,526 hp |

10.0 kW/kg |

6.10 hp/lb |

Boeing 777 |

| PWR RS-24 (SSME) Block II H2 Brayton turbopump[15][16] |

63,384 kW |

85,000 hp |

138 kW/kg |

84 hp/lb |

Space Shuttle (STS-110 and later) [•] |

| PWR RS-24 (SSME) Block I H2 Brayton turbopump[2] |

53,690 kW |

72,000 hp |

153 kW/kg |

93 hp/lb |

Space Shuttle |

- Full vehicle power-to-weight ratio shown below

Electric motors/Electromotive generators

An

electric motor uses

electrical energy to provide

mechanical work, usually through the interaction of a

magnetic field and

current-carrying conductors. By the interaction of mechanical work on an electrical conductor in a magnetic field,

electrical energy can be

generated.

- Full vehicle power-to-weight ratio shown below

Fluid engines and fluid pumps

Fluids (liquid and gas) can be used to transmit and/or store energy using

pressure and other fluid properties.

Hydraulic (liquid) and

pneumatic (gas) engines convert fluid pressure into other desirable

mechanical or electrical work. Fluid pumps convert mechanical or electrical work into movement or pressure changes of a fluid, or storage in a

pressure vessel.

Thermoelectric generators and electrothermal actuators

A variety of effects can be harnessed to produce

thermoelectricity,

thermionic emission,

pyroelectricity and

piezoelectricity.

Electrical resistance and

ferromagnetism of materials can be harnessed to generate thermoacoustic energy from an electric current.

Electrochemical (galvanic) and electrostatic cell systems

(Closed cell) batteries

All electrochemical cell batteries deliver a changing voltage as

their chemistry changes from "charged" to "discharged". A nominal output

voltage and a cutoff voltage are typically specified for a battery by

its manufacturer. The output voltage falls to the cutoff voltage when

the battery becomes "discharged". The nominal output voltage is always

less than the open-circuit voltage produced when the battery is

"charged". The temperature of a battery can affect the power it can

deliver, where lower temperatures reduce power. Total energy delivered

from a single charge cycle is affected by both the battery temperature

and the power it delivers. If the temperature lowers or the power demand

increases, the total energy delivered at the point of "discharge" is

also reduced.

Battery discharge profiles are often described in terms of a factor of

battery capacity.

For example a battery with a nominal capacity quoted in ampere-hours

(Ah) at a C/10 rated discharge current (derived in amperes) may safely

provide a higher discharge current - and therefore higher

power-to-weight ratio - but only with a lower energy capacity.

Power-to-weight ratio for batteries is therefore less meaningful without

reference to corresponding energy-to-weight ratio and cell temperature.

This relationship is known as

Peukert's law.

[34]

Electrostatic, electrolytic and electrochemical capacitors

Capacitors store electric charge onto two electrodes separated by an electric field semi-insulating (

dielectric) medium. Electrostatic capacitors feature planar electrodes onto which electric charge accumulates.

Electrolytic capacitors use a liquid electrolyte as one of the electrodes and the

electric double layer effect upon the surface of the dielectric-electrolyte boundary to increase the amount of charge stored per unit volume.

Electric double-layer capacitors extend both electrodes with a

nanopourous material such as

activated carbon

to significantly increase the surface area upon which electric charge

can accumulate, reducing the dielectric medium to nanopores and a very

thin high

permittivity separator.

While capacitors tend not to be as temperature sensitive as

batteries, they are significantly capacity constrained and without the

strength of chemical bonds suffer from self-discharge. Power-to-weight

ratio of capacitors is usually higher than batteries because charge

transport units within the cell are smaller (electrons rather than

ions), however energy-to-weight ratio is conversely usually lower.

Fuel cell stacks and flow cell batteries

Fuel cells and

flow cells, although perhaps using similar chemistry to batteries, have the distinction of not containing the energy storage medium or

fuel.

With a continuous flow of fuel and oxidant, available fuel cells and

flow cells continue to convert the energy storage medium into electric

energy and waste products. Fuel cells distinctly contain a fixed

electrolyte whereas flow cells also require a continuous flow of

electrolyte. Flow cells typically have the fuel dissolved in the

electrolyte.

- Full vehicle power-to-weight ratio shown below

Photovoltaics

Vehicles

Power-to-weight ratios for vehicles are usually calculated using

Curb weight

(for cars) or wet weight (for motorcycles) – in other words, excluding

weight of the driver and any cargo. This could be slightly misleading,

especially with regard to motorcycles, where the driver might weigh 1/3

to 1/2 as much as the vehicle itself. In the sport of competitive

cycling athlete's performance is increasingly being expressed in

VAMs

and thus as a power-to-weight ratio in W/kg. This can be measured

through the use of a bicycle powermeter or calculated from measuring

incline of a road climb and the rider's time to ascend it.

[82]

Utility and practical vehicles

Most vehicles are designed to meet passenger comfort and cargo

carrying requirements. Different designs trade off power-to-weight ratio

to increase comfort, cargo space,

fuel economy,

emissions control,

energy security and endurance.

Reduced drag and

lower rolling resistance

in a vehicle design can facilitate increased cargo space without

increase in the (zero cargo) power-to-weight ratio. This increases the

role flexibility of the vehicle. Energy security considerations can

trade off power (typically decreased) and weight (typically increased),

and therefore power-to-weight ratio, for

fuel flexibility or

drive-train hybridisation. Some utility and practical vehicle variants such as

hot hatches and

sports-utility vehicles reconfigure power (typically increased) and weight to provide the perception of

sports car like performance or for other

psychological benefit.

Rail locomotives require high mass to maintain adhesive traction on the

rails, therefore improving the power-to-weight ratio by reducing mass

is not necessarily beneficial. However choice of rail locomotive

traction system (i.e.

AC VFD over DC) can support improved power-to-weight ratio by reducing mass for the same adhesion.

Notable low ratio

| Vehicle |

Power |

Weight |

Power-to-weight ratio |

| Benz Patent Motorwagen 954 cc 1886[83] |

560 W / 0.75 bhp |

265 kg / 584 lb |

2.1 W/kg / 779 lb/hp |

| Stephenson's Rocket 0-2-2 steam locomotive with tender 1829[84] |

15 kW / 20 bhp |

4,320 kg / 9524 lb |

3.5 W/kg / 476 lb/hp |

| CBQ Zephyr streamliner diesel locomotive with railcars 1934[85] |

492 kW / 660 bhp |

94 t / 208,000 lb |

5.21 W/kg / 315 lb/hp |

| Alberto Contador's Verbier climb 2009 Tour de France on Specialized bike[82] |

420 W / 0.56 bhp |

62 kg / 137 lb |

6.7 W/kg / 245 lb/hp |

| Force Motors Minidor Diesel 499 cc auto rickshaw[86][87] |

6.6 kW / 8.8 bhp |

700 kg / 1543 lb |

9 W/kg / 175 lb/hp |

| PRR Q2 4-4-6-4 steam locomotive with tender 1944 |

5,956 kW / 7,987 bhp |

475.9 t / 1,049,100 lb |

12.5 W/kg / 131 lb/hp |

| Mercedes-Benz Citaro O530BZ H2 fuel cell bus 2002[88] |

205 kW / 275 bhp |

14,500 kg / 32,000 lb |

14.1 W/kg / 116 lb/hp |

| TGV BR Class 373 high-speed Eurostar Trainset 1993 |

12,240 kW / 16,414 bhp |

816 t / 1,798,972 lb |

15 W/kg / 110 lb/hp |

| General Dynamics M1 Abrams Main battle tank 1980[89] |

1,119 kW / 1500 bhp |

55.7 t / 122,800 lb |

20.1 W/kg / 81.9 lb/hp |

| BR Class 43 high-speed diesel electric locomotive 1975 |

1,678 kW / 2,250 bhp |

70.25 t / 154,875 lb |

23.9 W/kg / 69 lb/hp |

| GE AC6000CW diesel electric locomotive 1996 |

4,660 kW / 6,250 bhp |

192 t / 423,000 lb |

24.3 W/kg / 68 lb/hp |

| BR Class 55 Napier Deltic diesel electric locomotive 1961 |

2,460 kW / 3,300 bhp |

101 t / 222,667 lb |

24.4 W/kg / 68 lb/hp |

| International CXT 2004[90] |

164 kW / 220 bhp |

6,577 kg / 14500 lb |

25 W/kg / 66 lb/hp |

| Ford Model T 2.9 L flex-fuel 1908 |

15 kW / 20 bhp |

540 kg / 1,200 lb |

28 W/kg / 60 lb/hp |

| TH!NK City 2008[91] |

30 kW / 40 bhp |

1038 kg / 2,288 lb |

28.9 W/kg / 56.9 lb/hp |

| Messerschmitt KR200 Kabinenroller 191 cc 1955 |

6 kW / 8.2 bhp |

230 kg / 506 lb |

30 W/kg / 50 lb/hp |

| Wright Flyer 1903 |

9 kW / 12 bhp |

274 kg / 605 lb |

33 W/kg / 50 lb/hp |

| Tata Nano 624 cc 2008 |

26 kW / 35 bhp |

635 kg / 1,400 lb |

41.0 W/kg / 40 lb/hp |

| Bombardier JetTrain high-speed gas turbine-electric locomotive 2000[92] |

3,750 kW / 5,029 bhp |

90,750 kg / 200,000 lb |

41.2 W/kg / 39.8 lb/hp |

| Suzuki MightyBoy 543 cc 1988 |

23 kW / 31 bhp |

550 kg / 1,213 lb |

42 W/kg / 39 lb/hp |

| Mitsubishi i MiEV 2009[93] |

47 kW / 63 bhp |

1,080 kg / 2,381 lb |

43.5 W/kg / 37.8 lb/hp |

| Holden FJ 2,160 cc 1953[94] |

44.7 kW / 60 bhp |

1,021 kg / 2,250 lb |

43.8 W/kg / 37.5 lb/hp |

| Chevrolet Kodiak/GMC Topkick LYE 6.6 L 2005[1][95] |

246 kW / 330 bhp |

5126 kg / 11,300 lb |

48 W/kg / 34.2 lb/hp |

| DOE/NASA/0032-28 Chevrolet Celebrity 502 cc ASE Mod II 1985[5] |

62.3 kW / 83.5 bhp |

1,297 kg / 2,860 lb |

48.0 W/kg / 34.3 lb/hp |

| Suzuki Alto 796 cc 2000 |

35 kW / 46 bhp |

720 kg / 1,587 lb |

49 W/kg / 35 lb/hp |

| Land Rover Defender 2.4 L 1990[96] |

90 kW / 121 bhp |

1,837 kg / 4,050 lb |

49 W/kg / 33 lb/hp |

Common power

| Vehicle |

Power |

Weight |

Power-to-weight ratio |

| Toyota Prius 1.8 L 2010 (petrol only)[97] |

73 kW / 98 bhp |

1,380 kg / 3,042 lb |

53 W/kg / 31 lb/hp |

| Bajaj Platina Naked 100 cc 2006[98] |

6 kW / 8 bhp |

113 kg / 249 lb |

53 W/kg / 31 lb/hp |

| Subaru R2 type S 2003[99] |

47 kW / 63 bhp |

830 kg / 1,830 lb |

57 W/kg / 29 lb/hp |

| Ford Fiesta ECOnetic 1.6 L TDCi 5dr 2009[100] |

66 kW / 89 bhp |

1,155 kg / 2,546 lb |

57 W/kg / 29 lb/hp |

| Volvo C30 1.6D DRIVe S/S 3dr Hatch 2010[101] |

80 kW / 108 bhp |

1,347 kg / 2,970 lb |

59.4 W/kg / 27.5 lb/hp |

| Ford Focus ECOnetic 1.6 L TDCi 5dr Hatch 2009[102] |

81 kW / 108 bhp |

1,357 kg / 2,992 lb |

59.7 W/kg / 27 lb/hp |

| Ford Focus 1.8 L Zetec S TDCi 5dr Hatch 2009[103] |

84 kW / 113 bhp |

1,370 kg / 3,020 lb |

61 W/kg / 27 lb/hp |

| Honda FCX Clarity 4 kg Hydrogen 2008[104] |

100 kW / 134 bhp |

1,600 kg / 3,528 lb |

63 W/kg / 26 lb/hp |

| Hummer H1 6.6 L V8 2006[105] |

224 kW / 300 bhp |

3,559 kg / 7,847 lb |

63 W/kg / 26 lb/hp |

| Audi A2 1.4 L TDI 90 type S 2003[106] |

66 kW / 89 bhp |

1,030 kg / 2,270 lb |

64 W/kg / 25 lb/hp |

| Opel/Vauxhall/Holden/Chevrolet Astra 1.7 L CTDi 125 2010[107] |

92 kW / 123 bhp |

1,393 kg / 3,071 lb |

66 W∕kg / 24.9 lb∕hp |

| Mini (new) Cooper 1.6D 2007[108] |

81 kW / 108 bhp |

1,185 kg / 2,612 lb |

68 W/kg / 24 lb/hp |

| Toyota Prius 1.8 L 2010 (electric boost)[97] |

100 kW / 134 bhp |

1,380 kg / 3,042 lb |

72 W/kg / 23 lb/hp |

| Ford Focus 2.0 L Zetec S TDCi 5dr Hatch 2009[109] |

100 kW / 134 bhp |

1,370 kg / 3,020 lb |

73 W/kg / 23 lb/hp |

| General Motors EV1 electric car Gen II 1998[110] |

102.2 kW / 137 bhp |

1,400 kg / 3,086 lb |

73 W/kg / 23 lb/hp |

| Toyota Venza I4 2.7 L FWD 2009[111] |

136 kW / 182 bhp |

1,706 kg / 3,760 lb |

80 W/kg / 20.7 lb/hp |

| Ford Focus 2.0 L Zetec S 5dr Hatch 2009[112] |

107 kW / 143 bhp |

1,327 kg / 2,926 lb |

81 W/kg / 20 lb/hp |

| Fiat Grande Punto 1.6 L Multijet 120 2005[113] |

88 kW / 118 bhp |

1,075 kg / 2,370 lb |

82 W/kg / 20 lb/hp |

| Mini (classic) 1275GT 1969 |

57 kW / 76 bhp |

686 kg / 1,512 lb |

83 W/kg / 20 lb/hp |

| Opel/Vauxhall/Holden/Chevrolet Astra 2.0 L CTDi 160 2010[114] |

118 kW / 158 bhp |

1,393 kg / 3,071 lb |

85 W∕kg / 19.4 lb∕hp |

| Ford Focus 2.0 auto 2007[115] |

104.4 kW / 140 bhp |

1,198 kg / 2,641 lb |

87.1 W/kg / 19 lb/hp |

| Subaru Legacy/Liberty 2.0R 2005[116] |

121 kW / 162 bhp |

1,370 kg / 3,020 lb |

88 W/kg / 19 lb/hp |

| Subaru Outback 2.5i 2008[117] |

130.5 kW / 175 bhp |

1,430 kg / 3,153 lb |

91 W/kg / 18 lb/hp |

| Smart Fortwo 1.0 L Brabus 2009[118] |

72 kW / 97 bhp |

780 kg / 1,720 lb |

92 W/kg / 18 lb/hp |

| Toyota Venza V6 3.5 L AWD 2009[111] |

200 kW / 268 bhp |

1,835 kg / 4,045 lb |

109 W/kg / 15 lb/hp |

| Toyota Venza I4 2.7 L FWD 2009[111] with Lotus mass reduction[119] |

136 kW / 182 bhp |

1,210 kg / 2,667 lb |

112.2 W/kg / 14.7 lb/hp |

| Toyota Hilux V6 DOHC 4 L 4×2 Single Cab Pickup ute 2009[120] |

175 kW / 235 bhp |

1,555 kg / 3,428 lb |

112.5 W/kg / 14.6 lb/hp |

| Toyota Venza V6 3.5 L FWD 2009[111] |

200 kW / 268 bhp |

1,755 kg / 3,870 lb |

114 W/kg / 14.4 lb/hp |

Performance luxury, roadsters and mild sports

Increased engine performance is a consideration, but also other features associated with

luxury vehicles.

Longitudinal engines are common. Bodies vary from

hot hatches,

sedans (saloons),

coupés,

convertibles and

roadsters. Mid-range

dual-sport and

cruiser motorcycles tend to have similar power-to-weight ratios.

Sports vehicles and aircraft

Power-to-weight ratio is an important vehicle characteristic that

affects the acceleration and handling - and therefore the driving

enjoyment - of any sports vehicle. Aircraft also depend on high

power-to-weight ratio to achieve sufficient

lift.

| Vehicle |

Power |

Weight |

Power-to-weight ratio |

| Lotus Elise SC 2008 |

163 kW / 218 bhp |

910 kg / 2006 lb |

179 W/kg / 9 lb/hp |

| Ferrari Testarossa 1984 |

291 kW / 390 bhp |

1506 kg / 3320 lb |

193 W/kg / 9 lb/hp |

| Artega GT[129] |

220 kW / 300 bhp |

1100 kg / 2425 lb |

200 W/kg / 8 lb/hp |

| Lotus Exige GT3 2006[130] |

202.1 kW / 271 bhp |

980 kg / 2160 lb |

206 W/kg / 8 lb/hp |

| Chevrolet Corvette C6[131] |

321 kW / 430 bhp |

1441 kg / 3177 lb |

223 W/kg / 7 lb/hp |

| Suzuki V-Strom 650 V-twin DualSport 650 cc |

50 kW / 67 bhp |

194 kg / 427 lb |

258 W/kg / 6.4 lb/hp |

| Chevrolet Corvette C6 Z06[131] |

376 kW / 505 bhp |

1421 kg / 3133 lb |

265 W/kg / 6.2 lb/hp |

| Porsche 911 GT2 2007 |

390 kW / 523 bhp |

1440 kg / 3200 lb |

271 W/kg / 6.1 lb/hp |

| Lamborghini Murciélago LP 670-4 SV 2009[132] |

493 kW / 661 bhp |

1550 kg / 3417 lb |

318 W/kg / 5.1 lb/hp |

| McLaren F1 GT 1997[133] |

467.6 kW / 627 bhp |

1220 kg / 2690 lb |

403 W/kg / 4.3 lb/hp |

| Bombardier Dash 8 Q400 turboprop airliner[134] |

7,562 kW / 10,142 bhp |

17,185 kg / 37,888 lb |

440 W/kg / 3.7 lb/hp |

| Supermarine Spitfire Fighter aircraft 1936 |

1,096 kW / 1,470 bhp |

2,309 kg / 5,090 lb |

475 W/kg / 3.46 lb/hp |

| Messerschmitt Bf 109 Fighter aircraft 1935 |

1,085 kW / 1,455 bhp |

2,247 kg / 4,954 lb |

483 W/kg / 3.40 lb/hp |

| Thunderbolt Land speed record car |

3504 kW / 4700 bhp |

7 t / 15432 lb |

500 W/kg / 3.28 lb/hp |

| Ferrari FXX 2005 |

597 kW / 801 bhp |

1155 kg / 2546 lb |

517 W/kg / 3.2 lb/hp |

| Polaris Industries Assault Snowmobile 2009[135] |

115 kW / 154 bhp |

221 kg / 487 lb |

523 W/kg / 3.16 lb/hp |

| Ultima GTR 720 2006[136] |

536.9 kW / 720 bhp |

920 kg / 2183 lb |

583 W/kg / 3 lb/hp |

| Honda CBR1000RR 2009 |

133 kW / 178 bhp |

199 kg / 439 lb |

668 W/kg / 2.5 lb/hp |

| Ariel Atom 500 V8 2011 |

372 kW / 500 bhp |

550 kg / 1212 lb |

676.3 W/kg / 2.45 lb/hp |

| Peugeot 208 T16 Pikes Peak 2013 |

652 kW / 875 bhp |

875 kg / 1930 lb |

745 W/kg / 2.2 lb/hp |

| KillaCycle Drag racing electric motorcycle |

260 kW / 350 bhp |

281 kg / 619 lb |

925 W/kg / 1.77 lb/hp |

| MTT Turbine Superbike 2008[137] |

213.3 kW / 286 bhp |

227 kg / 500 lb |

940 W/kg / 1.75 lb/hp |

| Vyrus 987 C3 4V V supercharged motorcycle 2010[138] |

157.3 kW / 211 bhp |

158 kg / 348.3 lb |

996 W/kg / 1.65 lb/hp |

| BMW Williams FW27 Formula One 2005[139] |

690 kW / 925 bhp |

600 kg / 1323 lb |

1150 W/kg / 1.43 lb/hp |

| Honda RC211V MotoGP 2004-6 |

176.73 kW / 237 bhp |

148 kg / 326 lb |

1194 W/kg / 1.37 lb/hp |

| Boeing 747-300[10] at Mach 0.84 cruise, 35,000 ft altitude[disputed – discuss] |

245 MW / 328,656 bhp |

178.1 t / 392,800 lb |

1376 W/kg / 1.20 lb/hp |

| John Force Racing Funny Car NHRA Drag Racing 2008[140] |

5,963.60 kW / 8,000 bhp |

1043 kg / 2,300 lb |

5717 W/kg / 0.30 lb/hp |

Supersonic vehicles

Some sports and

aerospace vehicles are capable of exceeding the speed of sound. Vehicles in this class must account for

transonic wave drag,

shock waves and

aerodynamic heating.

Turbojet,

turbofan,

ramjet,

afterburner and

rocket propulsion is common. Note that with rockets and air breathing jet engines,

vehicle power is proportional to vehicle speed,

since rockets (and to a lesser extent air breathing jet engines) give a

thrust that is completely independent of speed, this means that there

is no upper limit to any particular rocket's power-to-weight ratio

provided it has been given sufficient initial speed.

Readers of this table should treat the comparison data with caution because factors such as

altitude,

aerodynamic drag,

intake design, the

density of air at a given altitude and prevailing weather condition, as well as the varying

speed of sound at different altitudes and under different weather conditions, all conspire to make such a comparison have little or no

predictive power. There is no

dynamometer for rockets and aircraft.

| Vehicle |

Power |

Weight |

Power-to-weight ratio |

| Space Shuttle Endeavour (OV-105)[16][141] |

190 MW / 255,000 bhp |

78 t / 172,000 lb |

2,437 W/kg / 0.7 lb/hp |

| Aérospatiale/BAC Concorde 1969 at Mach 2.02 supercruise full thrust |

330 MW / 443,143 bhp |

78.7 t / 173,500 lb |

4,199 W/kg / 0.39 lb/hp |

| Thrust Super Sonic Car |

82 MW / 110,000 bhp |

10.5 t / 23,149 lb |

7,812 W/kg / 0.21 lb/hp |

| F-35 Lightning II Multirole combat aircraft 2006 at Mach 1.67 full thrust |

110 MW / 146,922 bhp |

13,300 kg / 29,300 lb |

8,238 W/kg / 0.20 lb/hp |

| Sukhoi Su-35BM Multirole combat aircraft 2008 at Mach 2.25 full thrust |

188.5 MW / 252,842 bhp |

18,400 kg / 40,500 lb |

10,247 W/kg / 0.16 lb/hp |

| Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird Surveillance aircraft 1966 at Mach 3.2, 290 kN thrust |

318.3 MW / 426,853 bhp |

30,600 kg / 67,461 lb |

10,402 W/kg / 0.16 lb/hp |

| Sukhoi T-50 Stealth multirole fighter aircraft 2010 at Mach 2, 294 kN thrust |

201 MW / 270,620 bhp |

18,500 kg / 40,786 lb |

10,908 W/kg / 0.15 lb/hp |

| F-22 Raptor Air superiority fighter aircraft 2009 at Mach 2.25, 312 kN thrust[142] |

241 MW / 323,088 bhp |

19,700 kg / 43,430 lb |

12,230 W/kg / 0.13 lb/hp |

| Rockwell X-30 scramjet SSTO spaceplane 1986 at Mach 30, 1.4 MN thrust (proposed) |

14 GW / 19,300,000 bhp |

136 t / 300,000 lb |

105,740 W∕kg / 0.016 lb/hp |

| Space Shuttle Endeavour (OV-105)[16][141] with SLWT and 2 SRBs[143][144][145] |

33 GW / 44,000,000 bhp |

280 t / 616,500 lb |

118,000 W/kg / 0.014 lb/hp |

See also

which equals

which equals  . This fact allows one to express the power-to-weight ratio purely by SI base units.

. This fact allows one to express the power-to-weight ratio purely by SI base units. , whose center of mass is to be accelerated along a straight line to a speed

, whose center of mass is to be accelerated along a straight line to a speed  and angle

and angle  with respect to the centre and radial of a gravitational field by an onboard powerplant, then the associated kinetic energy to be delivered to the body is equal to

with respect to the centre and radial of a gravitational field by an onboard powerplant, then the associated kinetic energy to be delivered to the body is equal to is mass of the body

is mass of the body is speed of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is speed of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is acceleration of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is acceleration of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is linear force - or thrust - applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is linear force - or thrust - applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is torque applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is torque applied upon the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is angular velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time.

is angular velocity of the center of mass of the body, changing with time. is linear speed of the center of mass of the body.

is linear speed of the center of mass of the body.

No comments:

Post a Comment