From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

EO-1 Satellite Image of Johnston Atoll.

|

|||

|

|

|||

| Geography | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Coordinates | 16°45′N 169°31′WCoordinates: 16°45′N 169°31′W | ||

| Archipelago | North Pacific | ||

| Total islands | 4 | ||

| Area | 2.67 km2 (1.03 sq mi) | ||

| Highest elevation | 2 m (7 ft) | ||

| Country | |||

|

Johnston Atoll is under the administration of the United States Fish and Wildlife Service |

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Population | 0 | ||

| Additional information | |||

| unincorporated | |||

Johnston Atoll is an unincorporated territory of the United States administered by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service of the Department of the Interior as part of the Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument. The island is visited annually by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Public entry is only by special-use permit and generally restricted to scientists and educators.[1]

For nearly 70 years, the atoll was under the control of the American military. In that time it was used as a bird sanctuary, naval refueling depot, airbase, nuclear and biological weapons testing, for space recovery, as a secret missile base, and as a chemical weapon and Agent Orange storage and disposal site. These activities left the island environmentally contaminated and remediation and monitoring continues. In 2004 the U.S. military base was closed and control of the island was handed over to civilian authorities of the United States Government.

Contents

- 1 Geography

- 2 History

- 2.1 Early history

- 2.2 National Wildlife Refuge

- 2.3 Military control

- 2.4 Sand Island Seaplane base

- 2.5 Airfield

- 2.6 World War II 1941-1945

- 2.7 Coast Guard mission 1957-1992

- 2.8 National nuclear weapon test site 1958-1963

- 2.9 Anti-Satellite mission 1962-1975

- 2.10 Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center

- 2.11 Biological Warfare test site 1965

- 2.12 Chemical Weapon Storage 1971-2001

- 2.13 Agent Orange Storage 1972-1977

- 2.14 Chemical Weapon Demilitarization Mission 1990-2000

- 2.15 Closure and remaining structures

- 2.16 Contamination

- 3 Demographics

- 4 See also

- 5 References

- 6 External links

Geography

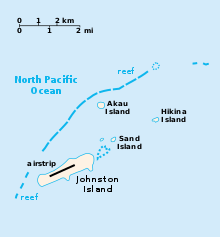

Johnston Atoll is an uninhabited 1.03 sq mi (2.7 km2) atoll in the North Pacific Ocean. Johnston Atoll is located between the Marshall Islands and the Hawaii Islands about 750 nmi (860 mi; 1,390 km) southwest of the island of Hawai'i.[1] The atoll, which is located on a coral reef platform, comprises four islands. Johnston (or Kalama) Island and Sand Island are both enlarged natural features, while Akau (North) and Hikina (East) are two artificial islands formed by coral dredging.[1] Johnston Atoll is grouped as one of the United States Minor Outlying Islands.| Island | Original Size 1942 (ha) |

Final Size 1964 (ha) |

|---|---|---|

| Johnston Island | 19 | 241 |

| Sand Island | 4 | 9 |

| North (Akau) Island | - | 10 |

| East (Hikina) Island | - | 7 |

| Johnston Atoll | 23 | 267 |

| Lagoon | 13,000 | 13,000 |

History

The unofficial flag of Johnston Atoll. The official flag for all U.S. minor outlying islands is the U.S. flag.

Early history

The first Western record of the atoll was on September 2, 1796 when the American brig Sally accidentally grounded on a shoal near the islands. The ship's captain, Joseph Pierpont, published his experience in several American newspapers the following year giving an accurate position of Johnston and Sand Island along with part of the reef. However he did not name or lay claim to the area.[2] The islands were not officially named until Captain Charles J. Johnston of the Royal Naval ship HMS Cornwallis sighted them on December 14, 1807.In 1858 William Parker and R. F. Ryan, chartered the schooner Palestine specifically to find Johnston Atoll. They located guano on the atoll in March 1858 and they proceeded to claim the island under the Guano Islands Act. By 1858, Johnston Atoll was claimed by both the United States and the Kingdom of Hawaii. In June 1858, Samuel Allen, sailing on the Kalama, tore down the U.S. flag and raised the Hawaiian flag. On July 27, 1858, the atoll was declared part of the domain of King Kamehameha IV. However, later that year King Kamehameha revoked the lease granted to Allen when the King learned that the atoll had been claimed previously by the United States.[3] By 1890 the atoll's guano deposits had been entirely depleted (mined out) by U.S. interests operating under the Guano Islands Act.

National Wildlife Refuge

From July 10–22, 1923, the atoll was recorded in a pioneering aerial photography project. Days later on July 29, 1923 by Executive Order No. 4467, President Calvin Coolidge established Johnston Atoll as a federal bird refuge and placed it under the control of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. [4] Johnston Atoll was added to the United States National Wildlife Refuge system in 1926 to protect the tropical ecosystem and the wildlife that it harbors.[5]After the bases closing, The Atoll was administered by the Pacific Remote Islands National Wildlife Refuge Complex. The outer islets and water rights were part administered by the Fish and Wildlife Service while the actual Johnston Island land mass remained under Navy control for cleanup purposes. However on January 6, 2009, under authority of section 2 of the Antiquities Act, The Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument was established by President George W. Bush to administer and protect Johnston Island along with six other Pacific islands.[6] The monument includes 696 acres (2.82 km2) of land and over 800,000 acres (3,200 km2) of water area.[7]

Military control

On December 29, 1934, President Franklin D. Roosevelt with Executive Order 6935 transferred control of Johnston Atoll to the United States Navy in order to establish an air station, and also to the Department of the Interior to administer the bird refuge. In 1948 the U.S Air Force assumed control of the Atoll.[8]During the Operation Hardtack nuclear test series administration of Johnston Atoll was assigned to the Commander of Joint Task Force Seven from April 22-August 19, 1958. After the tests were completed, the island reverted back to the command of the US Air Force.[9]

Sand Island Seaplane base

On May 26, 1942 a United States Navy Consolidated PBY-5 Catalina wrecked at Johnston Atoll. The Catalina pilot made a normal power landing and immediately applied throttle for take-off. At a speed of about fifty knots the plane swerved to the left and then continued into a violent waterloop. The hull of the plane was broken open and the Catalina sank immediately. [11]

After the war on March 27, 1949 a PBY-6A Catalina had to make a forced landing during flight from Kwajalein to Johnston Island. The plane was damaged beyond repair and the crew of 11 was rescued nine hours later by a Navy ship which sank the plane by gunfire.[12] During 1958, a proposed support agreement for Navy Seaplane operations at Johnston Island was under discussion though it was never completed because a requirement for the operation failed to materialize.[13]

Airfield

Main article: Johnston Atoll Airport

By September 1941 construction of an airfield

on Johnston Island commenced. A 4,000 feet (1,200 m) by 500 feet

(150 m) runway was built together with two 400-man barracks, two mess

halls, a cold-storage building, an underground hospital, a fresh-water

plant, shop buildings and fuel storage. The runway was complete by

December 7, 1941.[14] and was subsequently lengthened and improved each time that the island was enlarged.Continental Air Micronesia served the island commercially, touching down between Honolulu and Majuro. When an aircraft landed it was surrounded by armed soldiers and the passengers were not allowed to leave the aircraft. Aloha Airlines also made weekly scheduled flights to the island carrying civilian and military personnel, in the 1990's there were flights almost daily, and some days saw up to 3 arrivals.

There were several times when the runway was needed for emergency landings for both civil and military aircraft, including one landing by a Qantas Boeing 747. When the Army decommissioned the runway, it could not then be used as an emergency landing place to calculate flight routes across the Pacific. The nearest emergency runways are now 1,300 and 1,420 miles away.[15]

As of 2003, the airfield at Johnston Atoll consisted of a closed single 9,000 feet (2,700 m) asphalt/concrete runway 5/23, a parallel taxiway, and a large paved ramp along the south-east side of the runway.

World War II 1941-1945

Main article: Shelling of Johnston and Palmyra

In February 1941 Johnston Atoll was designated as a Naval Defensive

Sea Area and Airspace Reservation. On December 15, 1941 the atoll was

shelled by a Japanese submarine outside the reef, several buildings were

hit, but no personnel were injured.[14] Additional shelling occurred on December 22 and 23, 1941.In July 1942 the civilian contractors at the atoll were replaced by 500 men from the 5th and 10th Naval Construction Battalions, who expanded the fuel storage and water production at the base and built additional facilities. The 5th Battalion departed in January 1943.[14] In December 1943 the 99th Naval Construction Battalion arrived at the atoll and proceeded to lengthen the runway to 6,000 feet (1,800 m) and add an additional 10 acres (4.0 ha) of parking to the seaplane base.[16] During world War II, Johnson Atoll was used as a submarine and aircraft refueling stop for American bombers transiting the Pacific ocean including the Boeing B-29 Enola Gay.[17]

Coast Guard mission 1957-1992

On November 1, 1957, a United States Coast Guard LORAN-A station was commissioned (on Sand Island) which switched to a LORAN-C station in 1979. The station was disestablished on July 1, 1992.[18]National nuclear weapon test site 1958-1963

Successes

Between 1958 and 1975, Johnston Atoll area was used as an American national nuclear test site for High-altitude nuclear explosions. In 1958 Johnston Atoll participated in the "Hardtack I" nuclear test. The U.S. military used Johnston atoll for two nuclear tests during the series. The August 1, 1958 test codenamed "Teak" and the August 12, 1958 test codenamed "Orange" both involved 3.8-megaton explosions from rockets launched from Johnston Atoll. Johnston Island is also known to have been used to launch 124 sounding rockets reaching up to 1158 kilometers altitude with scientific and data instrumentation either in support of nuclear tests or in experiments related to anti-satellite technology.[19][20]One of these, "Starfish Prime" on July 9, 1962, was a 1.4 megaton explosion, created by a W49 warhead at an altitude of 400 kilometers. It created a fireball and artificial aurora visible in Hawaii, along with an electromagnetic pulse that disrupted power and communications as far away as Hawaii. It also pumped enough radiation into the Van Allen belts to destroy or seriously degrade seven orbiting satellites.

The final Fishbowl launch that used a Thor missile carried the "Kingfish" 400 kiloton warhead up to its 98 km detonation altitude. Although it was officially one of the Operation Fishbowl tests, it is sometimes not listed among high-altitude nuclear tests because of its lower detonation altitude. "Tightrope" was the final test of Operation Fishbowl and detonated on November 3, 1962. It launched on a Nike-Hercules missile, and detonated at a lower altitude than the other Fishbowl tests. "At Johnston Island, there was an intense white flash. Even with high-density goggles, the burst was too bright to view, even for a few seconds. A distinct thermal pulse was also felt on the bare skin. A yellow-orange disc was formed, which transformed itself into a purple doughnut. A glowing purple cloud was faintly visible for a few minutes."[21] The nuclear yield was reported in most official documents only as being less than 20 kilotons. One report by the U.S. federal government reported the "Tightrope" test yield as 10 kilotons.[22] Seven rockets carrying scientific instrumentation were launched from Johnston Island in support of the Tightrope test, which was the final atmospheric test conducted by the United States.

Failures

The "Fishbowl" series included four failures, all of which were deliberately disrupted by range safety officers when the missiles systems failed during launch and were aborted. The second launch of the Fishbowl series "Bluegill", carrying an active warhead, and was "lost" by a defective range safety tracking radar and had to be destroyed 10 minutes after liftoff even though it probably ascended successfully. The subsequent nuclear weapon launch failures from Johnston Atoll caused serious contamination to the island and surrounding areas with weapons-grade Plutonium and Americium that remains an issue to this day.The failure of the "Bluegill" launch created in effect a dirty bomb but did not release the nuclear warhead's plutonium debris onto Johnston Atoll as the missile fell into the ocean south of the island and was not recovered. However, the "Starfish", "Bluegill Prime", and "Bluegill Double Prime" test launch failures in 1962 scattered radioactive debris over Johnston Island contaminating it, the lagoon, and Sand island with Plutonium for decades.[23][24]

"Bluegill Prime," the second attempt to launch the payload which failed last time was scheduled for 23:15 (local) on July 25, 1962. It too was a genuine disaster and caused the most serious Plutonium contamination on the island. The THOR missile was carrying one pod, two re-entry vehicles and the W50 nuclear warhead. The missile engine malfunctioned immediately after ignition, and the range safety officer fired the destruct system while the missile was still on the launch pad. The Johnston Island launch complex was demolished in the subsequent explosions and fire which burned through the night. The launch emplacement and portions of the island were contaminated with highly radioactive plutonium spread by the explosion, fire and wind-blown smoke.

On October 15, 1962 the "Bluegill Double Prime" test also misfired. During the test, the rocket was destroyed at a height of 109,000 feet after it malfunctioned 90 seconds into the flight. U.S. Defense Department officials confirm that when the rocket was destroyed, it contributed to the radioactive pollution on the island.

In 1963, the U.S. Senate ratified the Limited Test Ban Treaty, which contained a provision known as "Safeguard C". Safeguard C was the basis for maintaining Johnston Atoll as a "ready to test" above-ground nuclear testing site should atmospheric nuclear testing ever be deemed to be necessary again. In 1993, Congress appropriated no funds for the Johnston Atoll "Safeguard C" mission, bringing it to an end.

Anti-Satellite mission 1962-1975

Main article: Program 437

Program 437 turned the PGM-17 Thor

into an operational anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon system, a capability

that was kept top secret even after it was deployed. The Program 437

mission was approved for development by U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert

McNamara on November 20, 1962 and based at the Atoll. Program 437 used

modified Thor missiles that had been returned from deployment in Great

Britain and was the second deployed U.S. operational nuclear

anti-satellite operation. Eighteen more suborbital Thor launches took

place from Johnston Island during the 1964-1975 period in support of

Program 437. In 1965-1966 four Program 437 Thors were launched with

'Alternate Payloads' for satellite inspection. This was evidently an

elaboration of the system to allow visual verification of the target

before destroying it. These flights may have been related to the late

1960's Program 922, a non-nuclear version of Thor with infrared homing

and a high explosive warhead. Thors were kept positioned and active near

the two Johnston Island launch pads after 1964. However, partly because

of the Vietnam war, in October 1970 the Department of Defense had

transferred Program 437 to standby status as an economic measure. The Strategic Arms Limitation Talks led to Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty

that prohibited 'interference with national means of verification'

which meant that ASAT's were not allowed, by treaty, to attack Russian

spy satellites. Thors were removed from Johnston Atoll and were stored

in mothballed war-reserve condition at Vandenberg AFB from 1970 until

the anti-satellite mission of Johnston Island facilities was ceased on

August 10, 1974 and the program was officially discontinued on April 1,

1975, when any possibility of restoring the ASAT program was finally

terminated. Eighteen Thor launches in support of the Program 437

Alternate Payload (AP) mission took place from Johnston Atoll's Launch

emplacements.[25]Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center

See also: SAMOS (satellite) and Mid-air retrieval

Satellite and Missile Observation System Project (SAMOS-E) or "E-6" was a relatively short-lived series of United States visual reconnaissance satellites in the early 1960s. SAMOS was also known by the unclassified terms Program 101 and Program 201.[26] The Air Force program was also used as a cover for the initial development of the Central Intelligence Agency's Key Hole (including Corona and Gambit) reconnaissance satellites systems.[27] Imaging was performed with film cameras and television surveillance from polar low Earth orbits with film canisters retuning via capsule and parachute with mid-air retrieval. SAMOS was first launched in 1960, but not operational until 1963 with all of the missions being launched from Vandenberg AFB.[28]During the early months of the SAMOS program it was essential not only to hide the GAMBIT technical effort under a screen of E-6 activity, but also to make the orbital vehicle portions of the two systems resemble one another in outward appearance. Thus, some of the configuration details of SAMOS were decided less by engineering logic than by the need to camouflage GAMBIT and thus, in theory, a GAMBIT could be launched without alerting many people to its real nature. Problems relative to tracking networks, communications, and recovery were resolved with the decision in late February 1961 to use Johnston Island as the film capsule descent and recovery zone for the program.[29] On July 10, 1961 work was initiated on four buildings of the Johnston Island Recovery Operations Center for the National Reconnaissance Office. Men from the Johnston Atoll facility would recover the parachuting film canister capsules with a radar equipped JC-130 aircraft by capturing them in the air with a specialed recovery apparatus.[30]

The recovery center was also responsible for collecting the radioactive scientific data pods dropped from missiles following launch.[31]

Biological Warfare test site 1965

In March and April 1965 Johnston Atoll was used to launch biological attacks against U.S. Army and Navy vessels 100 miles South-west of Johnston island in vulnerability, defense and decontamination tests conducted by the Deseret Test Center during Project SHAD and Project 112. DTC 64-4 (Deseret Test Center) was originally called “RED BEVA” (Biological Evaluation) though the name was later changed to “Shady Grove” likely for operational security reasons. The biological agents released in the test included Francisella tularensis (formerly called Pateurella tularensis) (Agent UL), the causative agent of Tularemia; Coxiella burnetti (Agent OU), causative agent of Q fever; and Bacillus globigii (Agent BG).[32] During Project SHAD, Bacillus globigii was used to simulate biological warfare agents (such as Anthrax), because it was then considered a contaminant with little health consequence to humans however, BG is now considered a human pathogen.[33] Ships equipped with the E-2 multi-head disseminator and A-4C aircraft equipped with Aero 14B spray tanks released agents in nine aerial and four surface trials in phase B of the test series on February 12-March 15, 1965 and in four aerial trials in phase D of the test series on March 22-April 3, 1965.[32] According to SHAD Veteran Jack Alderson, area three at Johnston Atoll was located at the most downwind part of the island and consisted of an inflatable Nissen hut to be used for weapons preparation and some communications.[34]Chemical Weapon Storage 1971-2001

See also: Red Hat (U.S. military operation)

In 1970, Congress redefined the island's military mission as the

storage and destruction of chemical weapons. The Army leased 41 acres in

1971 to store chemical weapons held in Okinawa, Japan. Johnston Atoll

became a chemical weapons storage site in 1971 holding about 6.6 percent

of the U.S. military chemical weapon arsenal.[23] The Chemical weapons were brought from Okinawa under Operation Red Hat with the re-deployment of the 267th Chemical Company

and consisted of rockets, mines, artillery projectiles, and bulk 1-ton

containers filled with Sarin, Agent VX, vomiting agent, and blister

agent such as mustard gas. Chemical weapons from the Soloman islands and

Germany were also stored on the island after 1990.[35] Chemical agents were stored in the high security Red Hat Storage Area (RHSA) which included hardened igloos in the weapon storage area,

the Red Hat building (#850), two Red Hat hazardous waste warehouses

(#851 and #852), an open storage area, and security entrances and guard

towers.Agent Orange Storage 1972-1977

Main article: Agent_Orange#Johnston_Atoll

Agent Orange was bought to Johnston Atoll from South Vietnam and Gulfport, Mississippi in 1972 under Operation Pacer IVY

and stored on the northwest corner of the island known as the Herbicide

Orange Storage site but dubbed the "Agent Orange Yard". The Agent

Orange was eventually destroyed during Operation Pacer HO on the Dutch incineration ship MT Vulcanus

in the Summer of 1977. Leaking barrels during the storage and spills

during re-drumming operations contaminated the storage area, and lagoon

with herbicide residue and its contaminant 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin.Chemical Weapon Demilitarization Mission 1990-2000

Main article: JACADS

Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System

(JACADS) was the first full-scale chemical weapons disposal facility.

In 1981, the Army began planning for the Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent

Disposal System (JACADS). Built to incinerate chemical munitions on the

island, construction for the facility began in 1985 and was completed

five years later. Following completion of construction and facility

characterization, JACADS began operational verification testing (OVT) in

June 1990. From 1990 until 1993, the Army conducted four planned

periods of Operational Verification Testing (OVT), required by Public

Law 100-456. OVT was completed in March 1993, having demonstrated that

the reverse assembly incineration technology was effitive and that

JACADS operations met all environmental parameters. The OVT process

enabled the Army to gain critical insight into the factors that

establish a safe and effective rate of destruction for all munitions and

agent types. Only after this critical testing period did the Army

proceed with full-scale disposal operations at JACADS. Transition to

full-scale operations started in May 1993 but the facility did not begin

full-scale operations until August 1993.Chemical weapons from the Solomon Islands in 1991 and from West Germany in 1990 as part of Operation Steel Box were also brought to Johnston Atoll for disposal. All of the chemical weapons once stored on Johnston Island were demilitarized and the agents incinerated at JACADS with the process completing in 2000 followed by the destruction of legacy hazardous waste material associated with chemical weapon storage and cleanup. JACADS demolished by 2003 and the island was stripped of its remaining infrastructure, environmentally remediated and a monument dedicated to JACADS personnel was erected at the site.[35]

Closure and remaining structures

In 2003, structures and facilities, including those used in JACADS, were removed, and the runway was marked closed. The last flight out for official personnel was June 15, 2004. After this date, the base was completely deserted, with the only structures left standing being the Joint Operations Center (JOC) building at the east end of the runway, chemical bunkers in the weapon storage area and at least one nissan hut.[36]Built in 1964, the JOC is a 4-floor concrete and steel administration building for the island that has no windows and was built to withstand a category IV tropical cyclone as well as atmospheric nuclear tests. The building remains standing but was gutted entirely in 2004, during an asbestos abatement project. All doors of the JOC except one have been welded shut. The ground floor has a side building attached which served as a facility for decontamination that contained three long snaking corridors and 55 shower heads one could walk through during decontamination.[37]

Rows of bunkers in the Red Hat Storage Area remain intact however an agreement was established between the U.S. Army and EPA Region IX on August 21, 2003, that the Munitions Demilitarization Building (MDB) at JACADS would be demolished and the bunkers in the RHSA used for disposal of construction rubble and debris. After placement of the debris inside the bunkers, they were secured and the entries blocked with a concrete block barrier (a.k.a. King Tut Block) to prevent access to the bunker interior.[13]

Contamination

Over the years, leaks of Agent Orange as well as chemical weapon leaks in the weapon storage area where caustic chemicals such as sodium hydroxide where used to mitigate them during clean up. Larger spills of nerve and mustard agent within the MCD at JACADS also took place. Small releases of chemical weapon components from JACADS were cited by the EPA. Multiple studies of the Johnston Atoll environment and ecology have been conducted and the Atoll is likely the most studied island in the Pacific.[13]Dr. Lisa Lobel's work at the Atoll on the impact of PCB contamination in reef damselfish (Abudefduf sordidus) demonstrated that embryonic abnormalities could be utilized as a metric for comparing contaminated and uncontaminated areas.[38] Some PCB contamination in the lagoon was traced to Coast Guard disposal practices of PCB laden electrical transformers.

In 1962 Plutonium pollution following three failed nuclear missile launches was heaviest near the destroyed launch emplacement, in the lagoon offshore of the launch pad and near Sand Island. The contaminated launch site was stripped, the debris gathered and buried in the island's 1962 expansion. Since then, U.S. defense authorities surveyed the island in a series of studies, collected 45,000 tonnes of soil contaminated with radioactive isotopes that were placed into a fenced area covering 24 acres on the north of the island. The area was known as the Radiological Control Area, but dubbed "The Pluto' Yard" because its heavy contamination with highly radioactive Plutonium.[9][39] The Pluto yard is on the site of LE1 where the 1962 missile explosion occurred and also where a highly plutonium contaminated loading ramp was buried that was made for loading contaminated debris that was dumped at sea. Remediation included a plutonium "mining" operation called the Johnston Atoll Plutonium Contaminated Soil Cleanup Project. The collected radioactive soil and debris was buried in a landfill created within the former LE-1 area from June 2002 through November 11, 2002. Remediation at the Radiation Control Area included the construction of a 61 centimeters thick cap of coral sealing the landfill. Permanent markers were placed at each corner of the landfill to identify the landfill area.[13]

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1970 | 1,007 | — |

| 1980 | 327 | −67.5% |

| 1990 | 173 | −47.1% |

| 2000 | 1,100 | +535.8% |

| 2004 | 396 | −64.0% |

| 2005 | 361 | −8.8% |

| 2006 | 40 | −88.9% |

| 2007 | 0 | −100.0% |

The central means of transportation to this island was the airport which had a paved military runway or alternatively by ship via a pier and ship channel through the atoll's coral reef system. The islands were wired with 13 outgoing and 10 incoming commercial telephone lines, a 60-channel submarine cable, 22 DSN circuits by satellite, an Autodin with standard remote terminal, a digital telephone switch, the Military Affiliated Radio System (MARS station), a UHF/VHF air-ground radio, and a link to the Pacific Consolidated Telecommunications Network (PCTN) satellite.[citation needed] Amateur radio operators occasionally transmitted from the island, using the KH3 callsign prefix.

Johnston Atoll's economic activity was limited to providing services to American military personnel and the contractors residing temporarily on the island. The Island was regularly resupplied by barge and all foodstuffs and manufactured goods were imported. The base had six 2.5 megawatt (MW) electrical generators supplied by the base's support contractor, Holmes and Narver, using Enterprise Engine and Machinery Company DSR-36 diesel engines. The runway was also available to commercial airlines for emergency landings (a fairly common event), and for many years it was a regular stop on Continental Micronesia airline's "island hopper" service between Hawaii and the Marshall Islands.

There were no official license plates issued for use on Johnston Atoll. U.S. government vehicles were issued U.S. government license plates and private vehicles retained the plates from which they were registered. According to reputable license plate collectors, a number of "Johnston Atoll license plates" were created as souvenirs, and have even been sold on-line to collectors, but they were not officially issued.[40][41]

History since base was closed

The stripped Johnston Island was briefly offered for sale with several deed restrictions in 2006 as a “residence or vacation getaway,” with potential usage for “eco-tourism” by the General Services Administration's (GSA) Office of Real Property Utilization and Disposal. The sale included the unique postal zip code 96558, formerly assigned to the Armed Forces in the Pacific but did not include running water, electricity, or activation of the closed runway. The details of the offering were outlined on GSA's website and in a newsletter of the Center for Land Use Interpretation as unusual real estate listing # 6384, Johnston Island.[42][43]On August 22, 2006, Johnston Island was struck by Hurricane Ioke. The eastern eye-wall passed directly over the atoll, with winds exceeding 100 mph (160 km/h). Twelve people were actually on the island when the hurricane struck, part of a crew sent to the island to deliver a USAF contractor who sampled groundwater contamination levels. All 12 survived and one wrote a first hand account taking shelter from the storm in the JOC building.[37]

On December 9, 2007, the United States Coast Guard swept the runway at Johnston Island of debris and used the runway in the removal and rescue of an ill Taiwanese fisherman to Oahu, Hawaii. The fisherman was transferred from the Taiwanese fishing vessel Sheng Yi Tsai No. 166 to the Coast Guard buoy tender Kukui on December 6, 2007. The fisherman was transported to the island, and then picked up by a Coast Guard HC-130 Hercules rescue plane from Kodiak, Alaska.[44]

Since the base was closed, the atoll has been visited by many vessels crossing the Pacific, as the deserted atoll has a strong lure due to the activities once performed there. Visitor's have blogged about stopping there for during a trip or have posted photos of their visits.[45]

In 2010, a Fish and Wildlife survey team identified a swarm of Anoplolepis ants that had invaded the island. The crazy ants are particularly destructive to the native wildlife, and needed to be eradicated. A "Crazy Ant Strike Team" was formed to stay on the island for nine months to bait traps for the ants and eliminate them. The team camped in the old chemical weapons storage bunkers on the southwest corner of the island. It is believed that the ants arrived with private boaters visiting the island illegally.[46][47]

Wildlife

About 300 species of fish have been recorded from the reefs and inshore waters of the atoll. It is also visited by Green Turtles and Hawaiian Monk Seals. Seabird species recorded as breeding on the atoll include Bulwer's Petrel, Wedge-tailed Shearwater, Christmas Shearwater, White-tailed Tropicbird, Red-tailed Tropicbird, Brown Booby, Red-footed Booby, Masked Booby, Great Frigatebird, Spectacled Tern, Sooty Tern, Brown Noddy, Black Noddy and White Tern. It is visited by migratory shorebirds, including the Pacific Golden Plover, Wandering Tattler, Bristle-thighed Curlew, Ruddy Turnstone and Sanderling.[48]Areas

- Site location of Red Hat Storage Area aka the "Red Hat Area" 16.7234°N 169.5393°W

- Site location of the Radiological Control Area aka the "Pluto' Yard" (Plutonium Yard) 16.7303°N 169.5371°W

- Site location of the Herbicide Orange Storage Site aka Agent Orange Yard 16.7304°N 169.5359°W 16°43'37"N 169°32'45"W

- Site location of JACADS building, 16.7248°N 169.5327°W

- Joint Operations Center building (JOC), 16.7355°N 169.5233°W

- Site location of Scientific Row 16.7246°N 169.5399°W

- Runway 5/23 (closed) 16.7271°N 169.5384°W

- Site location of Navy Pier 16.7359°N 169.5279°W

- Site location of Wharf Area and Demilitarization Zone L site 16.7342°N 169.5310°W

- Location of Hama Point 16.7304°N 169.5212°W

- Location of bunker buildings 746 through 761 16.7250°N 169.5367°W

- Southwest Area 16.7209°N 169.5444°W

Launch facilities

- Johnston Island LC1 Redstone launch complex. Pad 1 16.7365°N 169.5222°W

- Johnston Island LC2 Redstone launch complex. Pad 2 16.7369°N 169.5226°W

- Johnston Island HAD23 Tomahawk Sandia launch complex. HAD Launcher 23 16.7375°N 169.5258°W

- Johnston Island UL6 Sandhawk launch complex. Universal Launcher 6 16.7374°N 169.5257°W

- Johnston Island LE1 Thor-Delta launch complex. Launch Emplacement 1 16.7288°N 169.5398°W

- Johnston Island LE2 Thor-Delta launch complex. Launch Emplacement 2 16.7288°N 169.5398°W

- Johnston Island S Johnston Island Operation Dominic south launchers 16.7370°N 169.5240°W

No comments:

Post a Comment