Gynoid

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Fembot" redirects here. For other uses, see Fembot (disambiguation).

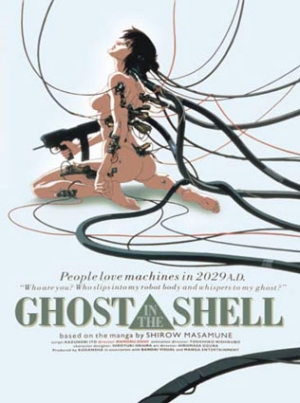

A gynoid is anything that resembles or pertains to the female human form. The term has more recently been applied to a humanoid robot

designed to more accurately look like a human female with much more

realism than normal androids, or of those with a sexual connotation.

However, it has not gained popular usage to refer specifically to female robots, as the term android is used almost universally to refer to robotic humanoids regardless of apparent gender. Android is perceived as implying a male-styled robot according to some cultural readings however.[1][2][3][4][5]The name is also used in American English medical terminology as a shortening of the term gynecoid (gynaecoid in British English).[6]

Contents

Name

The term gynoid was used by Gwyneth Jones in her 1985 novel Divine Endurance to describe a robot slave character in a futuristic China, that is judged by her beauty.[3]The portmanteau fembot (female robot) was popularized by the television series The Bionic Woman and later used in the Austin Powers films,[7] among others. Robotess is the oldest gender-specific term, originating in 1921 from the same source as robot.

Female robots

Examples of female robots include:- Project Aiko, an attempt at producing a realistic-looking female android. It speaks Japanese and English and has been produced for a price of 13000 Euros[8]

- EveR-1[9]

- Actroid, designed by Hiroshi Ishiguro to be "a perfect secretary who smiles and flutters her eyelids"[10]

- HRP-4C[11]

- Meinü robot[12][13]

As sexual devices

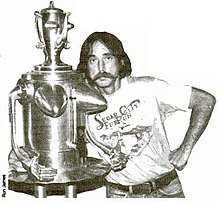

“Sweetheart”, shown with its creator, Clayton Bailey; the busty female

robot (also a functional coffee maker) that created a controversy when

it was displayed at the Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley.

Female robots as sexual devices have also appeared, with early constructions being crude. The first was produced by Sex Objects Ltd, a British company, for use as a "sex-aid". It was called simply "36C", from her chest measurement, and had a 16-bit microprocessor and voice synthesiser that allowed primitive responses to speech and push button inputs.[16]

Gynoids may be "eroticized", and some examples such as Aiko include sensitivity sensors in their breasts and genitals to facilitate sexual response.[17] The fetishization of gynoids in real life has been attributed to male desires for custom-made passive women, and has been compared to life-size sex dolls.[4]

In fiction

Artificial women have been a common trope in fiction and mythology since the writings of the ancient Greeks. This has continued with modern fiction, particularly in the genre of science fiction. In science fiction, female-appearing robots are often produced for use as domestic servants and sexual slaves, as seen in the film Westworld, Paul McAuley's novel Fairyland (1995), and Lester del Rey's short story "Helen O'Loy" (1938),[2] and sometimes as warriors, killers, or laborers.Metaphors

Misogyny

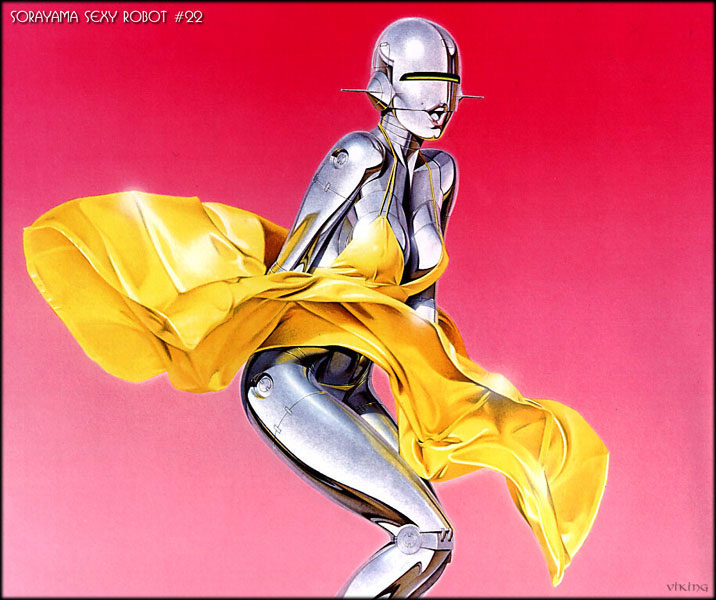

The treatment of gynoids in fiction has been seen as a metaphor for misogyny, as in the film Blade Runner, in which all three of the important female characters are gynoids, two of whom use their sexuality to attempt to manipulate or kill the protagonist Rick Deckard, often using sexualised imagery, such as when Pris attempts to strangle him between her thighs. Daniel Dinello writes that the violence with which the gynoids are treated represents Deckard's hatred of women. The third gynoid, Rachel, acts as a submissive female, even after Deckard "virtually rapes her".[2] Thomas Foster writes, about the novel Dead Girls by Richard Calder, that the technological bodies of gynoids depict sexism in an unnatural context, highlighting its negative impact. They also show that stereotypes and societal attitudes will not necessarily be altered through technological progress.[18]Japanese anime and manga both have a long tradition of female robot characters. The artist Hajime Sorayama is particularly influential, with his "sexy robot" images, found in his collection The Gynoids (1993).[19] These pieces depict primarily females with metallic skin. Some may interpret "gynoid" art as comments on gender and sexual conventions, and race, by highlighting the "whiteness" of the traditional pin-up girl.[20] The sexualised images of gynoids have also been interpreted as fetishisation of the female body, racial differences, and/or technology.[21]

Female freedom

Gynoids have also been used as a metaphor in feminist discourse, as part of cyborg feminism, representing female physical strength and freedom from the expectation to reproduce.[citation needed]The perfect woman

Étienne Maurice Falconet: Pygmalion et Galatée (1763). Although not robotic, Galatea's inorganic origin has led to comparisons with gynoids.

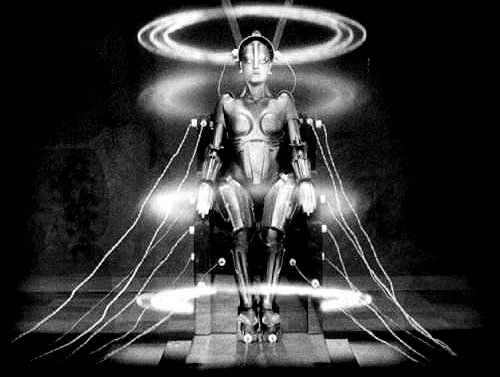

The first gynoid in film, the maschinenmensch ("machine-human"), also called "Parody", "Futura", "Robotrix", or the "Maria impersonator", in Fritz Lang's Metropolis is also an example: a femininely shaped robot is given skin so that she is not known to be a robot and successfully impersonates the imprisoned Maria and works convincingly as an exotic dancer.[1]

Such gynoids are designed according to cultural stereotypes of a perfect women, being "sexy, dumb, and obedient", and reflect the emotional frustration of their creators.[2] Fictional gynoids are often unique products made to fit a particular man's desire, as seen in the novel Tomorrow's Eve and films The Benumbed Woman, The Stepford Wives, Mannequin and Weird Science,[22] and the creators are often male "mad scientists" such as the characters Rotwang in Metropolis, Tyrell in Blade Runner, and the husbands in The Stepford Wives.[23] Gynoids have been described as the "ultimate geek fantasy: a metal-and-plastic woman of your own".[7]

The Bionic Woman television series coined the word fembot. These fembots were a line of powerful lifelike gynoids with the faces of protagonist Jaime Sommers's best friends.[24] They fought in two multi-part episodes of the series: "Kill Oscar" and "Fembots in Las Vegas", and despite the feminine prefix, there were also male versions, including some designed to impersonate particular individuals for the purpose of infiltration. While not truly artificially intelligent, the fembots still had extremely sophisticated programming that allowed them to pass for human in most situations. The term fembot was also used in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (referring to a robot duplicate of the title character, a.k.a. the Buffybot) and Futurama.

The 1987 science fiction cult movie Cherry 2000 also portrayed a gynoid character which was described by the male protagonist as his "perfect partner". The 1964 TV series My Living Doll features a robot, portrayed by Julie Newmar, who is similarly described.

Gender

Fiction about gynoids or female cyborgs reinforce essentialist ideas of femininity, according to Magret Grebowicz.[25] Such essentialist ideas may present as sexual or gender stereotypes. Among the few non-eroticized fictional gynoids include Rosie the Robot Maid[citation needed] from The Jetsons. However, she still has some stereotypically feminine qualities, such as a matronly shape and a predisposition to cry.[26]In a parody of the fembots from The Bionic Woman, attractive, blonde fembots in alluring baby-doll night-gowns were used as a lure for the fictional agent Austin Powers in the movie Austin Powers: International Man Of Mystery. The film's sequels had cameo appearances of characters revealed as fembots.

Judith Halberstam writes that these gynoids inform the viewer that femaleness does not indicate naturalness, and their exaggerated femininity and sexuality is used in a similar way to the title character's exaggerated masculinity, lampooning stereotypes.[27]

Sex objects

| Part of a series on |

| Sex and sexuality in speculative fiction |

|---|

Feminist critic Patricia Melzer writes in Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought that gynoids in Richard Calder's Dead Girls are inextricably linked to men's lust, and are mainly designed as sex-objects, having no use beyond "pleasing men's violent sexual desires".[29] The gynoid character Eve from the film Eve of Destruction has been described as "a literal sex bomb", with her subservience to patriarchal authority and a bomb in place of reproductive organs.[22] In the film The Perfect Women, the titular robot Olga is described as having "no sex", but Steve Chibnall writes in his essay "Alien Women" in British Science Fiction Cinema that it is clear from her fetishistic underwear that she is produced as a toy for men, with an "implicit fantasy of a fully compliant sex machine".[30] In the film West World, female robots actually engaged in intercourse with human men as part of the make-believe vacation world human customers paid to attend.

Sex with gynoids has been compared to necrophilia.[31] Sexual interest in gynoids and fembots has been attributed to fetishisation of technology, and compared to Sadomasochism in that it reorganizes the social risk of sex. The depiction of female robots minimizes the threat felt by men from female sexuality and allow the "erasure of any social interference in the spectator's erotic enjoyment of the image".[5] Gynoid fantasies are produced and collected by online communities centered around chat rooms and web-site galleries.[32]

Isaac Asimov writes that his robots were generally sexually neutral and that giving the majority masculine names was not an attempt to comment on gender. He first wrote about female-appearing robots at the request of editor Judy-Lynn del Rey.[33][34] Asimov's short story "Feminine Intuition" (1969) is an early example that showed gynoids as being as capable and versatile as male robots, with no sexual connotations.[35] Early models in "Feminine Intuition" were "female caricatures", used to highlight their human creators' reactions to the idea of female robots. Later models lost obviously feminine features, but retained "an air of femininity".[36]

In animation

Dr.Slump

In Dr.Slump anime and manga series, which is the debut series of Toriyama Akira, Dr.Senbei makes a fembot called Arale Norimaki which looks like a little girl. She is known for her naivety, energetic personality, lack of common sense, and amazingly unbelievable strength.See also

Cyborg

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Cyborg (disambiguation).

| Part of a series on |

| Cyborgs |

|---|

| Cyborgology |

| Theory |

| Centers |

| Politics |

The term cyborg is often applied to an organism that has restored function or enhanced abilities due to the integration of some artificial component or technology that relies on some sort of feedback.[3][4] While cyborgs are commonly thought of as mammals, they might also conceivably be any kind of organism and the term "Cybernetic organism" has been applied to networks, such as road systems, corporations and governments, which have been classed as such. The term can also apply to micro-organisms which are modified to perform at higher levels than their unmodified counterparts. It is hypothesized that cyborg technology will form a part of the future human evolution.

Some cyborgs may be represented as visibly mechanical (e.g. the Cybermen in the Doctor Who franchise or The Borg from Star Trek or Darth Vader from Star Wars); or as almost indistinguishable from humans (e.g. the Terminators from the Terminator films, the "Human" Cylons from the re-imagining of Battlestar Galactica etc.) The 1970s television series The Six Million Dollar Man featured one of the most famous fictional cyborgs, referred to as a bionic man; the series was based upon a novel by Martin Caidin titled Cyborg. Cyborgs in fiction often play up a human contempt for over-dependence on technology, particularly when used for war, and when used in ways that seem to threaten free will. Cyborgs are also often portrayed with physical or mental abilities far exceeding a human counterpart (military forms may have inbuilt weapons, among other things).

Contents

Overview

According to some definitions of the term, the metaphysical and physical attachments humanity has with even the most basic technologies have already made them cyborgs.[5] In a typical example, a human with an artificial cardiac pacemaker or implantable cardioverter-defibrillator would be considered a cyborg, since these devices measure voltage potentials in the body, perform signal processing, and can deliver electrical stimuli, using this synthetic feedback mechanism to keep that person alive. Implants, especially cochlear implants, that combine mechanical modification with any kind of feedback response are also cyborg enhancements. Some theorists cite such modifications as contact lenses, hearing aids, or intraocular lenses as examples of fitting humans with technology to enhance their biological capabilities; however, these modifications are as cybernetic as a pen or a wooden leg.The term is also used to address human-technology mixtures in the abstract. This includes not only commonly used pieces of technology such as phones, computers,super computers count also, the Internet, etc. but also artifacts that may not popularly be considered technology; for example, pen and paper, and speech and language. Augmented with these technologies, and connected in communication with people in other times and places, a person becomes capable of much more than they were before. This is like computers, which gain power by using Internet protocols to connect with other computers. Cybernetic technologies include highways, pipes, electrical wiring, buildings, electrical plants, libraries, and other infrastructure that we hardly notice, but which are critical parts of the cybernetics that we work within.

Bruce Sterling in his universe of Shaper/Mechanist suggested an idea of alternative cyborg called Lobster, which is made not by using internal implants, but by using an external shell (e.g. a Powered Exoskeleton).[6] Unlike human cyborgs that appear human externally while being synthetic internally, a Lobster looks inhuman externally but contains a human internally. The computer game Deus Ex: Invisible War prominently featured cyborgs called Omar, where "Omar" is a Russian translation of the word "Lobster" (since the Omar are of Russian origin in the game).

Origins

The concept of a man-machine mixture was widespread in science fiction before World War II. As early as 1843, Edgar Allan Poe described a man with extensive prostheses in the short story "The Man That Was Used Up". In 1908, Jean de la Hire introduced Nyctalope (perhaps the first true superhero was also the first literary cyborg) in the novel L'Homme Qui Peut Vivre Dans L'eau (The Man Who Can Live in the Water). Edmond Hamilton presented space explorers with a mixture of organic and machine parts in his novel The Comet Doom in 1928. He later featured the talking, living brain of an old scientist, Simon Wright, floating around in a transparent case, in all the adventures of his famous hero, Captain Future. He uses the term explicitly in the 1962 short story, "After a Judgment Day," to describe the "mechanical analogs" called "Charlies," explaining that "[c]yborgs, they had been called from the first one in the 1960s...cybernetic organisms." In the short story "No Woman Born" in 1944, C. L. Moore wrote of Deirdre, a dancer, whose body was burned completely and whose brain was placed in a faceless but beautiful and supple mechanical body.The term was coined by Manfred E. Clynes and Nathan S. Kline in 1960 to refer to their conception of an enhanced human being who could survive in extraterrestrial environments:

| “ | For the exogenously extended organizational complex functioning as an integrated homeostatic system unconsciously, we propose the term 'Cyborg'. - Manfred E. Clynes and Nathan S. Kline[7] | ” |

The term first appears in print five months earlier when The New York Times reported on the Psychophysiological Aspects of Space Flight Symposium where Clynes and Kline first presented their paper.

| “ | A cyborg is essentially a man-machine system in which the control mechanisms of the human portion are modified externally by drugs or regulatory devices so that the being can live in an environment different from the normal one.[8] | ” |

Cyborg tissues in engineering

Cyborgs tissues structured with carbon nanotubes and plant or fungal cells have been used in artificial tissue engineering to produce new materials for mechanical and electrical uses. The work was presented by Di Giacomo and Maresca at MRS 2013 Spring conference on Apr, 3rd, talk number SS4.04.[10] The cyborg obtained is inexpensive, light and has unique mechanical properties. It can also be shaped in desired forms. Cells combined with MWCNTs co-precipitated as a specific aggregate of cells and nanotubes that formed a viscous material. Likewise, dried cells still acted as a stable matrix for the MWCNT network. When observed by optical microscopy the material resembled an artificial “tissue” composed of highly packed cells. The effect of cell drying is manifested by their “ghost cell” appearance. A rather specific physical interaction between MWCNTs and cells was observed by electron microscopy suggesting that the cell wall (the most outer part of fungal and plant cells) may play a major active role in establishing a CNTs network and its stabilization. This novel material can be used in a wide range of electronic applications from heating to sensing and has the potential to open important new avenues to be exploited in electromagnetic shielding for radio frequency electronics and aerospace technology. In particular using Candida albicans cells cyborg tissue materials with temperature sensing properties have been reported. [11]Individual cyborgs

In current prosthetic applications, the C-Leg system developed by Otto Bock HealthCare is used to replace a human leg that has been amputated because of injury or illness. The use of sensors in the artificial C-Leg aids in walking significantly by attempting to replicate the user's natural gait, as it would be prior to amputation.[13] Prostheses like the C-Leg and the more advanced iLimb are considered by some to be the first real steps towards the next generation of real-world cyborg applications. Additionally cochlear implants and magnetic implants which provide people with a sense that they would not otherwise have had can additionally be thought of as creating cyborgs.

In vision science, direct brain implants have been used to treat non-congenital (acquired) blindness. One of the first scientists to come up with a working brain interface to restore sight was private researcher William Dobelle. Dobelle's first prototype was implanted into "Jerry", a man blinded in adulthood, in 1978. A single-array BCI containing 68 electrodes was implanted onto Jerry's visual cortex and succeeded in producing phosphenes, the sensation of seeing light. The system included cameras mounted on glasses to send signals to the implant. Initially, the implant allowed Jerry to see shades of grey in a limited field of vision at a low frame-rate. This also required him to be hooked up to a two-ton mainframe, but shrinking electronics and faster computers made his artificial eye more portable and now enable him to perform simple tasks unassisted.[14]

In 1997, Philip Kennedy, a scientist and physician designed the world's first human cyborg named Johnny Ray. Ray was a Vietnam veteran in Georgia who suffered a stroke. Unfortunately, Ray's body, as doctor's called it, was "locked in". Ray wanted his old life back so he agreed to Kennedy's experiment. Kennedy embedded a Neurotrophic Electrode near the part of Ray's brain so that Ray would be able to have some movement back in his body. The surgery went successfully, but in 2002, Johnny Ray passed away.[15]

In 2002, Canadian Jens Naumann, also blinded in adulthood, became the first in a series of 16 paying patients to receive Dobelle's second generation implant, marking one of the earliest commercial uses of BCIs. The second generation device used a more sophisticated implant enabling better mapping of phosphenes into coherent vision. Phosphenes are spread out across the visual field in what researchers call the starry-night effect. Immediately after his implant, Jens was able to use his imperfectly restored vision to drive slowly around the parking area of the research institute.[16]

In 2002, under the heading Project Cyborg, a British scientist, Kevin Warwick, had an array of 100 electrodes fired into his nervous system in order to link his nervous system into the Internet. With this in place he successfully carried out a series of experiments including extending his nervous system over the Internet to control a robotic hand, a loudspeaker and amplifier. This is a form of extended sensory input and the first direct electronic communication between the nervous systems of two humans.[17][18]

In 2004, under the heading Bridging the Island of the Colourblind Project, a British and completely color-blind artist, Neil Harbisson, started wearing an eyeborg on his head in order to hear colors.[19] His prosthetic device was included within his 2004 passport photograph which has been claimed to confirm his cyborg status.[20] In 2012 at TEDGlobal,[21] Harbisson explained that he did not feel like a cyborg when he started to use the eyeborg, he started to feel like a cyborg when he noticed that the software and his brain had united and given him an extra sense.[21]

Animal cyborgs

The US-based company Backyard Brains released what they refer to as "The world's first commercially available cyborg" called the RoboRoach. The project started as a University of Michigan biomedical engineering student senior design project in 2010[22] and was launched as an available beta product on 25 February 2011.[23] The RoboRoach was officially released into production via a TED talk at the TED Global conference,[24] and via the crowdsourcing website Kickstarter in 2013,[25] the kit allows students to use microstimulation to momentarily control the movements of a walking cockroach (left and right) using a bluetooth-enabled smartphone as the controller. Other groups have developed cyborg insects, including researchers at North Carolina State University[26] and UC Berkeley,[27] but the RoboRoach was the first kit available to the general public and was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as a device to serve as a teaching aid to promote an interest in neuroscience.[24] Several animal welfare organizations including the RSPCA [28] and PETA [29] have expressed concerns about the ethics and welfare of animals in this project.Social cyborgs

More broadly, the full term "cybernetic organism" is used to describe larger networks of communication and control. For example, cities, networks of roads, networks of software, corporations, markets, governments, and the collection of these things together. A corporation can be considered as an artificial intelligence that makes use of replaceable human components to function. People at all ranks can be considered replaceable agents of their functionally intelligent government institutions, whether such a view is desirable or not. The example above is reminiscent of the "organic paradigm" popular in the late 19th century due to the era's breakthroughs in understanding of cellular biology.Jaap van Till tries to quantify this effect with his Synthecracy Network Law: V ~ N !, where V is value and N is number of connected people. This factorial growth is what he claims leads to a herd or hive like thinking between large, electronically connected groups.

Cyborg proliferation in society

In finance

Due to advances in IT, human investors are able to employ super computers to engage in financial activities such as trading at faster speeds across borders than ever before. Because of the increasing reliance on artificial intelligence and advanced computerization, modern finance is becoming “cyborg finance,” because the key players are part human and part machine.The new cyborg investor is distinct from past conceptions of investors because this new investor conception is faster, more data driven, automated, and less human.

One key characteristic of cyborg finance is the use of incredibly powerful and fast computers to analyze and execute trading opportunities based on complex mathematical models. The software employing these algorithms is often proprietary and non-transparent, thus it is sometimes referred to as “black-box trading.”

In medicine

In medicine, there are two important and different types of cyborgs: the restorative and the enhanced. Restorative technologies "restore lost function, organs, and limbs".[30] The key aspect of restorative cyborgization is the repair of broken or missing processes to revert to a healthy or average level of function. There is no enhancement to the original faculties and processes that were lost.On the contrary, the enhanced cyborg "follows a principle, and it is the principle of optimal performance: maximising output (the information or modifications obtained) and minimising input (the energy expended in the process)".[31] Thus, the enhanced cyborg intends to exceed normal processes or even gain new functions that were not originally present.

Although prostheses in general supplement lost or damaged body parts with the integration of a mechanical artifice, bionic implants in medicine allow model organs or body parts to mimic the original function more closely. Michael Chorost wrote a memoir of his experience with cochlear implants, or bionic ear, titled "Rebuilt: How Becoming Part Computer Made Me More Human."[32] Jesse Sullivan became one of the first people to operate a fully robotic limb through a nerve-muscle graft, enabling him a complex range of motions beyond that of previous prosthetics.[33] By 2004, a fully functioning artificial heart was developed.[34] The continued technological development of bionic and nanotechnologies begins to raise the question of enhancement, and of the future possibilities for cyborgs which surpass the original functionality of the biological model. The ethics and desirability of "enhancement prosthetics" have been debated; their proponents include the transhumanist movement, with its belief that new technologies can assist the human race in developing beyond its present, normative limitations such as aging and disease, as well as other, more general incapacities, such as limitations on speed, strength, endurance, and intelligence. Opponents of the concept describe what they believe to be biases which propel the development and acceptance of such technologies; namely, a bias towards functionality and efficiency that may compel assent to a view of human people which de-emphasizes as defining characteristics actual manifestations of humanity and personhood, in favor of definition in terms of upgrades, versions, and utility.[35]

A brain-computer interface, or BCI, provides a direct path of communication from the brain to an external device, effectively creating a cyborg. Research of Invasive BCIs, which utilize electrodes implanted directly into the grey matter of the brain, has focused on restoring damaged eyesight in the blind and providing functionality to paralyzed people, most notably those with severe cases, such as Locked-In syndrome. This technology could enable people who are missing a limb or are in a wheelchair the power to control the devices that aide them through neural signals sent from the brain implants directly to computers or the devices. It is possible that this technology will also eventually be used with healthy people.[36]

Deep brain stimulation is a neurological surgical procedure used for therapeutic purposes. This process has aided in treating patients diagnosed with Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Tourette syndrome, epilepsy, chronic headaches, and mental disorders. After the patient is unconscious, through anesthesia, brain pacemakers or electrodes, are implanted into the region of the brain where the cause of the disease is present. The region of the brain is then stimulated by bursts of electrical current to disrupt the oncoming surge of seizures. Like all invasive procedures, deep brain stimulation may put the patient at a higher risk. However, there have been more improvements in recent years with deep brain stimulation than any available drug treatment.[37]

Retinal implants are another form of cyborgization in medicine. The theory behind retinal stimulation to restore vision to people suffering from retinitis pigmentosa and vision loss due to aging (conditions in which people have an abnormally low amount of ganglion cells) is that the retinal implant and electrical stimulation would act as a substitute for the missing ganglion cells (cells which connect the eye to the brain.)

While work to perfect this technology is still being done, there have already been major advances in the use of electronic stimulation of the retina to allow the eye to sense patterns of light. A specialized camera is worn by the subject, such as on the frames of their glasses, which converts the image into a pattern of electrical stimulation. A chip located in the user's eye would then electrically stimulate the retina with this pattern by exciting certain nerve endings which transmit the image to the optic centers of the brain and the image would then appear to the user. If technological advances proceed as planned this technology may be used by thousands of blind people and restore vision to most of them.

A similar process has been created to aide people who have lost their vocal cords. This experimental device would do away with previously used robotic sounding voice simulators. The transmission of sound would start with a surgery to redirect the nerve that controls the voice and sound production to a muscle in the neck, where a nearby sensor would be able to pick up its electrical signals. The signals would then move to a processor which would control the timing and pitch of a voice simulator. That simulator would then vibrate producing a multitonal sound which could be shaped into words by the mouth.[38]

An August 26, 2012 article from Harvard University's homepage, by Peter Reuell of the Harvard Gazette, proceeds to discuss three-dimensional cyborg tissue research, published in the journal Nature Materials, with possible medical implications done by Charles M. Lieber, the Mark Hyman Jr. Professor of Chemistry, and Daniel Kohane, a Harvard Medical School Anesthesiology Professor at Boston Children's Hospital.[39]

In the military

Military organizations' research has recently focused on the utilisation of cyborg animals for the purposes of a supposed tactical advantage. DARPA has announced its interest in developing "cyborg insects" to transmit data from sensors implanted into the insect during the pupal stage. The insect's motion would be controlled from a Micro-Electro-Mechanical System (MEMS) and could conceivably survey an environment or detect explosives and gas.[40] Similarly, DARPA is developing a neural implant to remotely control the movement of sharks. The shark's unique senses would then be exploited to provide data feedback in relation to enemy ship movement or underwater explosives.[41]In 2006, researchers at Cornell University invented[42] a new surgical procedure to implant artificial structures into insects during their metamorphic development.[43][44] The first insect cyborgs, moths with integrated electronics in their thorax, were demonstrated by the same researchers.[45][46] The initial success of the techniques has resulted in increased research and the creation of a program called Hybrid-Insect-MEMS, HI-MEMS. Its goal, according to DARPA's Microsystems Technology Office, is to develop "tightly coupled machine-insect interfaces by placing micro-mechanical systems inside the insects during the early stages of metamorphosis".[47]

The use of neural implants has recently been attempted, with success, on roaches. Surgically applied electrodes were put on the insect, which were remotely controlled by a human. The results, although sometimes different, basically showed that the roach could be controlled by the impulses it received through the electrodes. DARPA is now funding this research because of its obvious beneficial applications to the military and other areas[48]

In 2009 at the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Micro-electronic mechanical systems (MEMS) conference in Italy, researchers demonstrated the first "wireless" flying-beetle cyborg.[49] Engineers at the University of California at Berkeley have pioneered the design of a "remote controlled beetle", funded by the DARPA HI-MEMS Program. Filmed evidence of this can be viewed here.[50] This was followed later that year by the demonstration of wireless control of a "lift-assisted" moth-cyborg.[51]

Eventually researchers plan to develop HI-MEMS for dragonflies, bees, rats and pigeons.[52][53] For the HI-MEMS cybernetic bug to be considered a success, it must fly 100 metres (330 ft) from a starting point, guided via computer into a controlled landing within 5 metres (16 ft) of a specific end point. Once landed, the cybernetic bug must remain in place.[52]

In art

The concept of the cyborg is often associated with science fiction. However, many artists have tried to create public awareness of cybernetic organisms; these can range from paintings to installations. Some artists who create such works are Neil Harbisson, Moon Ribas, Patricia Piccinini, Steve Mann, Orlan, H. R. Giger, Lee Bul, Wafaa Bilal, Tim Hawkinson and Stelarc.Stelarc is a performance artist who has visually probed and acoustically amplified his body. He uses medical instruments, prosthetics, robotics, virtual reality systems, the Internet and biotechnology to explore alternate, intimate and involuntary interfaces with the body. He has made three films of the inside of his body and has performed with a third hand and a virtual arm. Between 1976–1988 he completed 25 body suspension performances with hooks into the skin. For 'Third Ear' he surgically constructed an extra ear within his arm that was internet enabled, making it a publicly accessible acoustical organ for people in other places.[54] He is presently performing as his avatar from his second life site.[55]

Tim Hawkinson promotes the idea that bodies and machines are coming together as one, where human features are combined with technology to create the Cyborg. Hawkinson's piece Emoter presented how society is now dependent on technology.[56]

Wafaa Bilal is an Iraqi-American performance artist who had a small 10 megapixel digital camera surgically implanted into the back of his head, part of a project entitled 3rd I.[57] For one year, beginning 15 December 2010, an image is captured once per minute 24 hours a day and streamed live to www.3rdi.me and the Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art. The site also displays Bilal's location via GPS. Bilal says that the reason why he put the camera in the back of the head was to make an "allegorical statement about the things we don't see and leave behind."[58] As a professor at NYU, this project has raised privacy issues, and so Bilal has been asked to ensure that his camera does not take photographs in NYU buildings.[58]

Machines are becoming more ubiquitous in the artistic process itself, with computerized drawing pads replacing pen and paper, and drum machines becoming nearly as popular as human drummers. This is perhaps most notable in generative art and music. Composers such as Brian Eno have developed and utilized software which can build entire musical scores from a few basic mathematical parameters.[59]

Scott Draves is a generative artist whose work is explicitly described as a "cyborg mind". His Electric Sheep project generates abstract art by combining the work of many computers and people over the internet.[60]

Artists as cyborgs

Artists have explored the term cyborg from a perspective involving imagination. Some work to make an abstract idea of technological and human-bodily union apparent to reality in an art form utilizing varying mediums, from sculptures and drawings to digital renderings. Artists that seek to make cyborg-based fantasies a reality often call themselves cyborg artists, or may consider their artwork "cyborg". How an artist or their work may be considered cyborg will vary depending upon the interpreter's flexibility with the term. Scholars that rely upon a strict, technical description of cyborg, often going by Norbert Wiener's cybernetic theory and Manfred E. Clynes and Nathan S. Kline's first use of the term, would likely argue that most cyborg artists do not qualify to be considered cyborgs.[61] Scholars considering a more flexible description of cyborgs may argue it incorporates more than cybernetics.[62] Others may speak of defining subcategories, or specialized cyborg types, that qualify different levels of cyborg at which technology influences an individual. This may range from technological instruments being external, temporary, and removable to being fully integrated and permanent.[63] Nonetheless, cyborg artists are artists. Being so, it can be expected for them to incorporate the cyborg idea rather than a strict, technical representation of the term,[64] seeing how their work will sometimes revolve around other purposes outside of cyborgism.[61]In body modification

As medical technology becomes more advanced, some techniques and innovations are adopted by the body modification community. While not yet cyborgs in the strict definition of Manfred Clynes and Nathan Kline, technological developments like implantable silicon silk electronics,[65] augmented reality[66] and QR codes[67] are bridging the disconnect between technology and the body. Hypothetical technologies such as digital tattoo interfaces[68][69] would blend body modification aesthetics with interactivity and functionality, bringing a transhumanist way of life into present day reality.In addition, it is quite plausible for anxiety expression to manifest. Individuals may experience pre-implantation feelings of fear and nervousness. To this end, individuals may also embody feelings of uneasiness, particularly in a socialized setting, due to their post-operative, technologically augmented bodies, and mutual unfamiliarity with the mechanical insertion. Anxieties may be linked to notions of otherness or a cyborged identity.[70]

In popular culture

Main article: Cyborgs in fiction

See also: Cyberpunk and List of fictional cyborgs

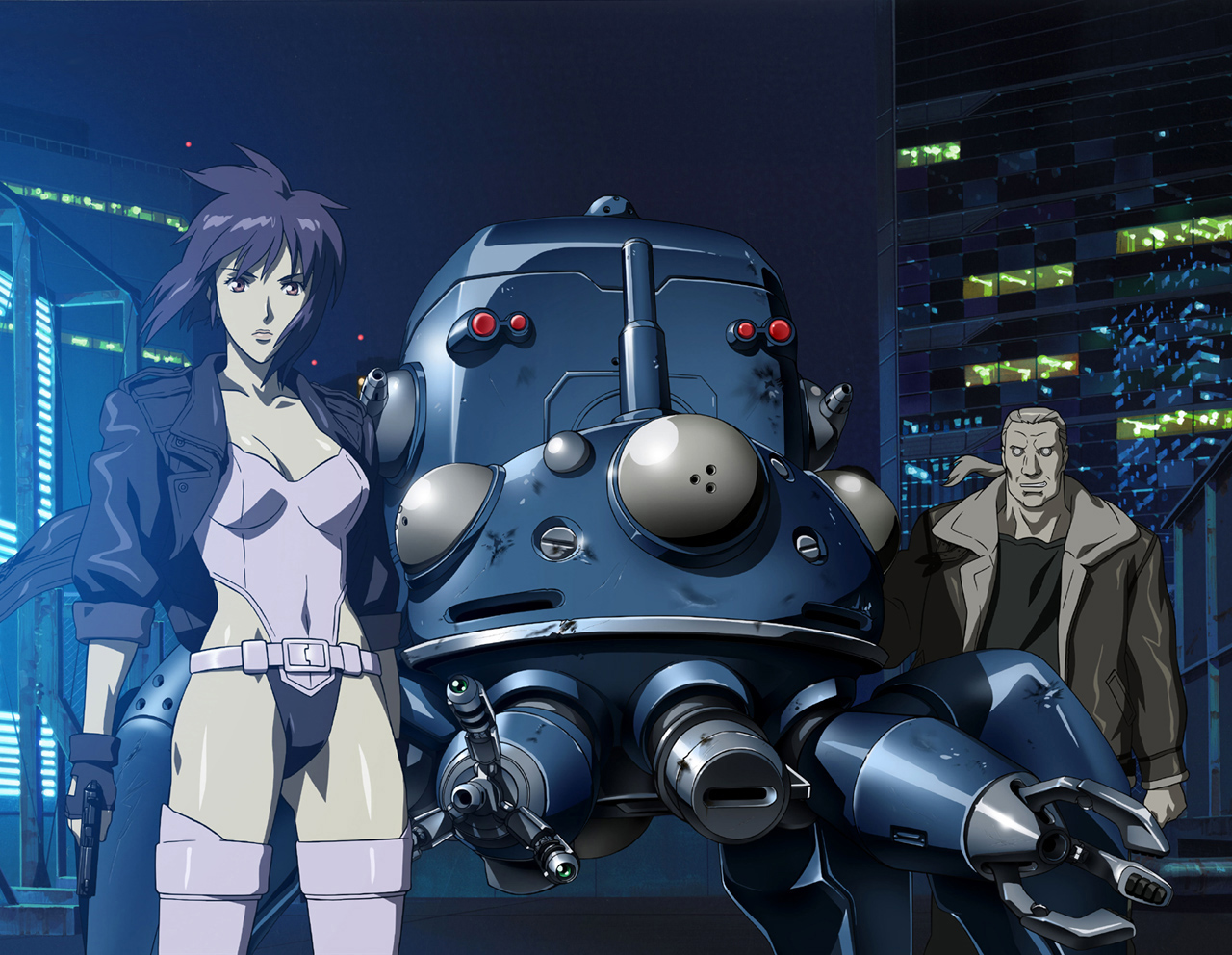

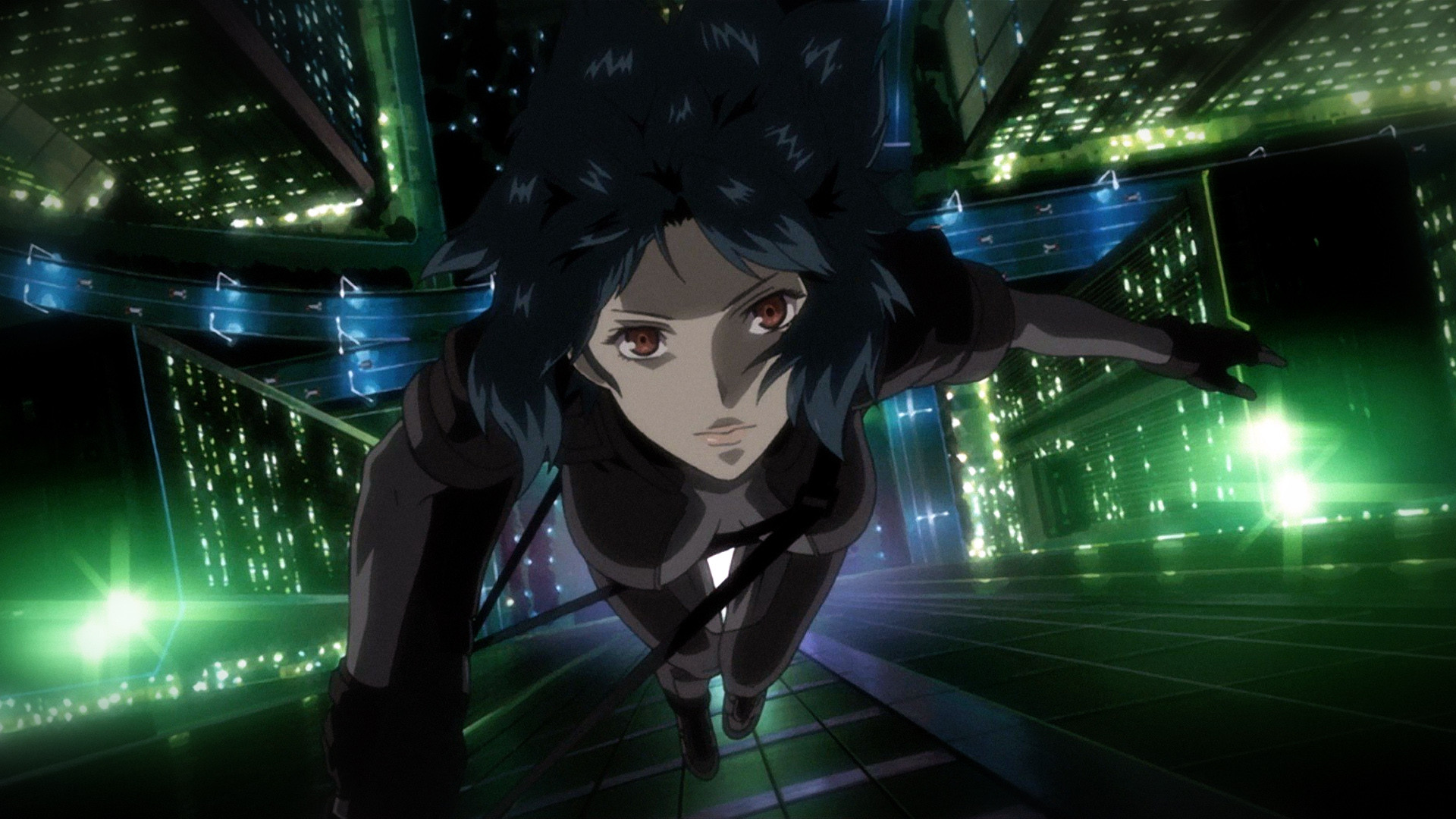

Cyborgs have become a well-known part of science fiction literature

and other media. Although many of these characters may be technically androids, they are often referred to as cyborgs. Well-known examples from film and television include RoboCop, Terminators, Evangelion, The Six Million Dollar Man, Replicants from Blade Runner, Daleks and Cybermen from Doctor Who, the Borg from Star Trek, Darth Vader and General Grievous from Star Wars, Inspector Gadget, and Cylons from the 2004 Battlestar Galactica series. From manga and anime are characters such as 8 Man (the inspiration for RoboCop), Kamen Rider, Ghost in the Shell's Motoko Kusanagi, as well as characters from western comic books like Tony Stark (after his Extremis and Bleeding Edge armor) and Victor "Cyborg" Stone. The Deus Ex videogame series deals extensively with the near-future rise of cyborgs and their corporate ownership, as does the Syndicate series.Cyborgization in critical deaf studies

Joseph Michael Valente, describes "cyborgization" as an attempt to codify "normalization" through cochlear implantation in young deaf children. Drawing from Paddy Ladd's work on Deaf epistemology and Donna Haraway's Cyborg ontology, Valente "use[s] the concept of the cyborg as a way of agitating constructions of cyborg perfection (for the deaf child that would be to become fully hearing)". He claims that cochlear implant manufacturers advertise and sell cochlear implants as a mechanical device as well as an uncomplicated medical "miracle cure". Valente criticizes cochlear implant researchers whose studies largely to date do not include cochlear implant recipients, despite cochlear implants having been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 1984.[71] Pamela J. Kincheloe discusses the representation of the cochlear implant in media and popular culture as a case study for present and future responses to human alteration and enhancement.[72]Cyborg Foundation

In 2010, the Cyborg Foundation became the world's first international organization dedicated to help humans become cyborgs.[73] The foundation was created by cyborg Neil Harbisson and Moon Ribas as a response to the growing amount of letters and emails received from people around the world interested in becoming a cyborg.[74] The foundation's main aims are to extend human senses and abilities by creating and applying cybernetic extensions to the body,[75] to promote the use of cybernetics in cultural events and to defend cyborg rights.[76] In 2010, the foundation, based in Mataró (Barcelona), was the overall winner of the Cre@tic Awards, organized by Tecnocampus Mataró.[77]In 2012, Spanish film director Rafel Duran Torrent, created a short film about the Cyborg Foundation. In 2013, the film won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival's Focus Forward Filmmakers Competition and was awarded with $100,000 USD.[78]

See also

Nyctalopics

Although there are varietals of cyborgs and applied cybernetics, the actual process of becoming a cyborg is known as nyctalopics. The term is coined after the first description of a cyborg, Nyctalope, who appeared in the works of Jean de La Hire.Biorobotics

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Biomechanical (disambiguation).

Biorobotics is often used to refer to a real subfield of robotics: studying how to make robots that emulate or simulate living biological organisms mechanically or even chemically. The term is also used in a reverse definition: making biological organisms as manipulatable and functional as robots, or making biological organisms as components of robots.

In the latter sense, biorobotics can be referred to as a theoretical discipline of comprehensive genetic engineering in which organisms are created and designed by artificial means. The creation of life from non-living matter for example, would be biorobotics. The field is in its infancy and is sometimes known as synthetic biology or bionanotechnology.

In fiction, biorobotics makes many appearances, like the biots of the novel Rendezvous with Rama or the replicants of the film Blade Runner.

Contents

Biorobotics in Fiction

Biorobotics has made many appearances in works of fiction, often in the form of synthetic biological organisms.The robots featured in Rossum's Universal Robots, the play that originally coined the term robot, are presented as synthetic biological entities closer to biological organisms than the mechanical objects that the term robot came to refer to. The replicants in the film Blade Runner are biological in nature: they are organisms of living tissue and cells created artificially. In the novel The Windup Girl by Paolo Bacigalupi, "windups" or "New People" are genetically engineered organisms.

The word biot, a portmanteau of "biological robot", was originally coined by Arthur C. Clarke in his 1972 novel Rendezvous with Rama. Biots are depicted as artificial biological organisms created to perform specific tasks on the space vessel Rama. This affects their physical attributes and cognitive abilities.

Humanoid Cylons in the 2004 television series Battlestar Galactica are another example of biological robots in fictions. Almost undistinguishable from humans, they are artificial creations created by mechanical cylons.

The authors of the Star Wars book series The New Jedi Order reprised the term biot. The Yuuzhan Vong uses the term to designate their biotechnology.

The term bioroid, or biological android, as also been used to designate artificial biological organisms, like in the manga Appleseed. In 1985 the animated Robotech television series popularized the term when it reused the term from the 1984 Japanese series The Super Dimension Cavalry Southern Cross.

In Warhammer 40k Imperium (Warhammer 40,000) uses servitors, vat-grown humans with cybernetic parts replacing most parts of the body.They lack emotions or intelligence and are only capable of simple tasks. A more advanced imperial robots are used by the imperium,Instead of using humans they are mostly machine and has biological brain and some other biological parts.Unlike servitors they are capable of having programmed instincts when killing but still they lack any true intelligence.

Practical experimentation

A biological brain, grown from cultured neurons which were originally separated, has been developed as the neurological entity subsequently embodied within a robot body by Kevin Warwick and his team at University of Reading. The brain receives input from sensors on the robot body and the resultant output from the brain provides the robot's only motor signals. The biological brain is the only brain of the robot.[1]Android (robot)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Mechanoid" redirects here. For other uses, see Mechanoid (disambiguation).

An android is a robot[1] or synthetic organism[2][3][4] designed to look and act like a human, especially one with a body having a flesh-like resemblance.[2] Until recently, androids have largely remained within the domain of science fiction, frequently seen in film and television. However, advancements in robot technology have allowed the design of functional and realistic humanoid robots.[5]Contents

Etymology

The word was coined from the Greek root ἀνδρ- 'man' and the suffix -oid 'having the form or likeness of'.[6]The Oxford English Dictionary traces the earliest use (as "Androides") to Ephraim Chambers' Cyclopaedia, in reference to an automaton that St. Albertus Magnus allegedly created.[3][7] The term "android" appears in US patents as early as 1863 in reference to miniature human-like toy automatons.[8] The term android was used in a more modern sense by the French author Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam in his work Tomorrow's Eve (1886).[3] This story features an artificial humanlike robot named Hadaly. As said by the officer in the story, "In this age of Realien advancement, who knows what goes on in the mind of those responsible for these mechanical dolls." The term made an impact into English pulp science fiction starting from Jack Williamson's The Cometeers (1936) and the distinction between mechanical robots and fleshy androids was popularized by Edmond Hamilton's Captain Future (1940–1944).[3]

Although Karel Čapek's robots in R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) (1921) – the play that introduced the word robot to the world – were organic artificial humans, the word "robot" has come to primarily refer to mechanical humans, animals, and other beings.[3] The term "android" can mean either one of these,[3] while a cyborg ("cybernetic organism" or "bionic man") would be a creature that is a combination of organic and mechanical parts.

The term "droid", coined by George Lucas for the original Star Wars film and now used widely within science fiction, originated as an abridgment of "android", but has been used by Lucas and others to mean any robot, including distinctly non-human form machines like R2-D2. The word "android" was used in Star Trek: The Original Series episode What Are Little Girls Made Of? The abbreviation "andy", coined as a pejorative by writer Philip K. Dick in his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, has seen some further usage, such as within the TV series Total Recall 2070.[9]

Authors have used the term android in more diverse ways than robot or cyborg. In some fictional works, the difference between a robot and android is only their appearance, with androids being made to look like humans on the outside but with robot-like internal mechanics.[3] In other stories, authors have used the word "android" to mean a wholly organic, yet artificial, creation.[3] Other fictional depictions of androids fall somewhere in between.[3]

Eric G. Wilson, who defines androids as a "synthetic human being", distinguishes between three types of androids, based on their body's composition:

- the mummy type - where androids are made of "dead things" or "stiff, inanimate, natural material", such as mummies, puppets, dolls and statues

- the golem type - androids made from flexible, possibly organic material, including golems and homunculi

- the automaton type - androids which are a mix of dead and living parts, including automatons and robots[4]

Projects

Japan

The Intelligent Mechatronics Lab, directed by Hiroshi Kobayashi at the Tokyo University of Science, has developed an android head called Saya, which was exhibited at Robodex 2002 in Yokohama, Japan. There are several other initiatives around the world involving humanoid research and development at this time, which will hopefully introduce a broader spectrum of realized technology in the near future. Now Saya is working at the Science University of Tokyo as a guide.

The Waseda University (Japan) and NTT Docomo's manufacturers have succeeded in creating a shape-shifting robot WD-2. It is capable of changing its face. At first, the creators decided the positions of the necessary points to express the outline, eyes, nose, and so on of a certain person. The robot expresses its face by moving all points to the decided positions, they say. The first version of the robot was first developed back in 2003. After that, a year later, they made a couple of major improvements to the design. The robot features an elastic mask made from the average head dummy. It uses a driving system with a 3DOF unit. The WD-2 robot can change its facial features by activating specific facial points on a mask, with each point possessing three degrees of freedom. This one has 17 facial points, for a total of 56 degrees of freedom. As for the materials they used, the WD-2's mask is fabricated with a highly elastic material called Septom, with bits of steel wool mixed in for added strength. Other technical features reveal a shaft driven behind the mask at the desired facial point, driven by a DC motor with a simple pulley and a slide screw. Apparently, the researchers can also modify the shape of the mask based on actual human faces. To "copy" a face, they need only a 3D scanner to determine the locations of an individual's 17 facial points. After that, they are then driven into position using a laptop and 56 motor control boards. In addition, the researchers also mention that the shifting robot can even display an individual's hair style and skin color if a photo of their face is projected onto the 3D Mask.

Korea

KITECH researched and developed EveR-1, an android interpersonal communications model capable of emulating human emotional expression via facial "musculature" and capable of rudimentary conversation, having a vocabulary of around 400 words. She is 160 cm tall and weighs 50 kg, matching the average figure of a Korean woman in her twenties. EveR-1's name derives from the Biblical Eve, plus the letter r for robot. EveR-1's advanced computing processing power enables speech recognition and vocal synthesis, at the same time processing lip synchronization and visual recognition by 90-degree micro-CCD cameras with face recognition technology. An independent microchip inside her artificial brain handles gesture expression, body coordination, and emotion expression. Her whole body is made of highly advanced synthetic jelly silicon and with 60 artificial joints in her face, neck, and lower body; she is able to demonstrate realistic facial expressions and sing while simultaneously dancing. In South Korea, the Ministry of Information and Communication has an ambitious plan to put a robot in every household by 2020.[10] Several robot cities have been planned for the country: the first will be built in 2016 at a cost of 500 billion won, of which 50 billion is direct government investment.[11] The new robot city will feature research and development centers for manufacturers and part suppliers, as well as exhibition halls and a stadium for robot competitions. The country's new Robotics Ethics Charter will establish ground rules and laws for human interaction with robots in the future, setting standards for robotics users and manufacturers, as well as guidelines on ethical standards to be programmed into robots to prevent human abuse of robots and vice versa.[12]United States

Walt Disney and a staff of Imagineers created Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln that debuted at the 1964 New York World's Fair.[13]Hanson Robotics, Inc., of Texas and KAIST produced an android portrait of Albert Einstein, using Hanson's facial android technology mounted on KAIST's life-size walking bipedal robot body. This Einstein android, also called "Albert Hubo", thus represents the first full-body walking android in history (see video at [14]). Hanson Robotics, the FedEx Institute of Technology,[15] and the University of Texas at Arlington also developed the android portrait of sci-fi author Philip K. Dick (creator of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the basis for the film Blade Runner), with full conversational capabilities that incorporated thousands of pages of the author's works.[16] In 2005, the PKD android won a first place artificial intelligence award from AAAI.

United Kingdom

In 2001, Steve Grand OBE, creator of the computer game Creatures, created an android, or anthropoid, he named it Lucy. The intention was that she would have to learn everything, including how to use her mechanical vocal chords to speak. Her systems were made to be similar to a human's.Use in fiction

See also: List of fictional robots and androids

Androids are a staple of science fiction. Isaac Asimov pioneered the fictionalization of the science of robotics and artificial intelligence, notably in his 1950s series I, Robot and Foundation and Empire.[17]

One thing common to most fictional androids is that the real-life

technological challenges associated with creating thoroughly human-like

robots – such as the creation of strong artificial intelligence – are assumed to have been solved.[18]

Fictional androids are often depicted as mentally and physically equal

or superior to humans – moving, thinking and speaking as fluidly as

them.[3][18]The tension between the nonhuman substance and the human appearance – or even human ambitions – of androids is the dramatic impetus behind most of their fictional depictions.[4][18] Some android heroes seek, like Pinocchio, to become human, as in the films Bicentennial Man, Hollywood, Enthiran and A.I. Artificial Intelligence,[18] or Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Others, as in the film Westworld, rebel against abuse by careless humans.[18] Android hunter Deckard in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and its film adaptation Blade Runner discovers that his targets are, in some ways, more human than he is.[18] Android stories, therefore, are not essentially stories "about" androids; they are stories about the human condition and what it means to be human.[18]

One aspect of writing about the meaning of humanity is to use discrimination against androids as a mechanism for exploring racism in society, as in Blade Runner.[19] Perhaps the clearest example of this is John Brunner's 1968 novel Into the Slave Nebula, where the blue-skinned android slaves are explicitly shown to be fully human.[20] More recently, the androids Bishop and Annalee Call in the films Aliens and Alien Resurrection are used as vehicles for exploring how humans deal with the presence of an "Other".[21]

Female androids, or "gynoids", are often seen in science fiction, and can be viewed as a continuation of the long tradition of men attempting to create the stereotypical "perfect woman".[22] Examples include the Greek myth of Pygmalion and the female robot Maria in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Some gynoids, like Pris in Blade Runner, are designed as sex-objects, with the intent of "pleasing men's violent sexual desires,"[23] or as submissive, servile companions, such as in The Stepford Wives. Fiction about gynoids has therefore been described as reinforcing "essentialist ideas of femininity",[24] although others have suggested that the treatment of androids is a way of exploring racism and misogyny in society.[25]

No comments:

Post a Comment