From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"Fembot" redirects here. For other uses, see Fembot (disambiguation).

A gynoid is anything that resembles or pertains to the female human form. The term has more recently been applied to a humanoid robot

designed to more accurately look like a human female with much more

realism than normal androids, or of those with a sexual connotation.

However, it has not gained popular usage to refer specifically to female robots, as the term android is used almost universally to refer to robotic humanoids regardless of apparent gender. Android is perceived as implying a male-styled robot according to some cultural readings however.[1][2][3][4][5]The name is also used in American English medical terminology as a shortening of the term gynecoid (gynaecoid in British English).[6]

Contents

Name

The term gynoid was used by Gwyneth Jones in her 1985 novel Divine Endurance to describe a robot slave character in a futuristic China, that is judged by her beauty.[3]The portmanteau fembot (female robot) was popularized by the television series The Bionic Woman and later used in the Austin Powers films,[7] among others. Robotess is the oldest gender-specific term, originating in 1921 from the same source as robot.

Female robots

Examples of female robots include:- Project Aiko, an attempt at producing a realistic-looking female android. It speaks Japanese and English and has been produced for a price of 13000 Euros[8]

- EveR-1[9]

- Actroid, designed by Hiroshi Ishiguro to be "a perfect secretary who smiles and flutters her eyelids"[10]

- HRP-4C[11]

- Meinü robot[12][13]

As sexual devices

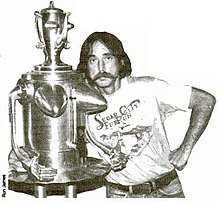

“Sweetheart”, shown with its creator, Clayton Bailey; the busty female

robot (also a functional coffee maker) that created a controversy when

it was displayed at the Lawrence Hall of Science at UC Berkeley.

Female robots as sexual devices have also appeared, with early constructions being crude. The first was produced by Sex Objects Ltd, a British company, for use as a "sex-aid". It was called simply "36C", from her chest measurement, and had a 16-bit microprocessor and voice synthesiser that allowed primitive responses to speech and push button inputs.[16]

Gynoids may be "eroticized", and some examples such as Aiko include sensitivity sensors in their breasts and genitals to facilitate sexual response.[17] The fetishization of gynoids in real life has been attributed to male desires for custom-made passive women, and has been compared to life-size sex dolls.[4]

In fiction

Artificial women have been a common trope in fiction and mythology since the writings of the ancient Greeks. This has continued with modern fiction, particularly in the genre of science fiction. In science fiction, female-appearing robots are often produced for use as domestic servants and sexual slaves, as seen in the film Westworld, Paul McAuley's novel Fairyland (1995), and Lester del Rey's short story "Helen O'Loy" (1938),[2] and sometimes as warriors, killers, or laborers.Metaphors

Misogyny

The treatment of gynoids in fiction has been seen as a metaphor for misogyny, as in the film Blade Runner, in which all three of the important female characters are gynoids, two of whom use their sexuality to attempt to manipulate or kill the protagonist Rick Deckard, often using sexualised imagery, such as when Pris attempts to strangle him between her thighs. Daniel Dinello writes that the violence with which the gynoids are treated represents Deckard's hatred of women. The third gynoid, Rachel, acts as a submissive female, even after Deckard "virtually rapes her".[2] Thomas Foster writes, about the novel Dead Girls by Richard Calder, that the technological bodies of gynoids depict sexism in an unnatural context, highlighting its negative impact. They also show that stereotypes and societal attitudes will not necessarily be altered through technological progress.[18]Japanese anime and manga both have a long tradition of female robot characters. The artist Hajime Sorayama is particularly influential, with his "sexy robot" images, found in his collection The Gynoids (1993).[19] These pieces depict primarily females with metallic skin. Some may interpret "gynoid" art as comments on gender and sexual conventions, and race, by highlighting the "whiteness" of the traditional pin-up girl.[20] The sexualised images of gynoids have also been interpreted as fetishisation of the female body, racial differences, and/or technology.[21]

Female freedom

Gynoids have also been used as a metaphor in feminist discourse, as part of cyborg feminism, representing female physical strength and freedom from the expectation to reproduce.[citation needed]The perfect woman

Étienne Maurice Falconet: Pygmalion et Galatée (1763). Although not robotic, Galatea's inorganic origin has led to comparisons with gynoids.

The first gynoid in film, the maschinenmensch ("machine-human"), also called "Parody", "Futura", "Robotrix", or the "Maria impersonator", in Fritz Lang's Metropolis is also an example: a femininely shaped robot is given skin so that she is not known to be a robot and successfully impersonates the imprisoned Maria and works convincingly as an exotic dancer.[1]

Such gynoids are designed according to patriarchal stereotypes of a perfect women, being "sexy, dumb, and obedient", and reflect the emotional frustration of their creators.[2] Fictional gynoids are often unique products made to fit a particular man's desire, as seen in the novel Tomorrow's Eve and films The Benumbed Woman, The Stepford Wives, Mannequin and Weird Science,[22] and the creators are often male "mad scientists" such as the characters Rotwang in Metropolis, Tyrell in Blade Runner, and the husbands in The Stepford Wives.[23] Gynoids have been described as the "ultimate geek fantasy: a metal-and-plastic woman of your own".[7]

The Bionic Woman television series coined the word fembot. These fembots were a line of powerful lifelike gynoids with the faces of protagonist Jaime Sommers's best friends.[24] They fought in two multi-part episodes of the series: "Kill Oscar" and "Fembots in Las Vegas", and despite the feminine prefix, there were also male versions, including some designed to impersonate particular individuals for the purpose of infiltration. While not truly artificially intelligent, the fembots still had extremely sophisticated programming that allowed them to pass for human in most situations. The term fembot was also used in Buffy the Vampire Slayer (referring to a robot duplicate of the title character, a.k.a. the Buffybot) and Futurama.

The 1987 science fiction cult movie Cherry 2000 also portrayed a gynoid character which was described by the male protagonist as his "perfect partner". The 1964 TV series My Living Doll features a robot, portrayed by Julie Newmar, who is similarly described.

Gender

Fiction about gynoids or female cyborgs reinforce essentialist ideas of femininity, according to Magret Grebowicz.[25] Such essentialist ideas may present as sexual or gender stereotypes. Among the few non-eroticized fictional gynoids include Rosie the Robot Maid[citation needed] from The Jetsons. However, she still has some stereotypically feminine qualities, such as a matronly shape and a predisposition to cry.[26]In a parody of the fembots from The Bionic Woman, attractive fembots in fuzzy see-through night-gowns were used as a lure for the fictional agent Austin Powers in the movie Austin Powers: International Man Of Mystery. The film's sequels had cameo appearances of characters revealed as fembots.

Judith Halberstam writes that these gynoids inform the viewer that femaleness does not indicate naturalness, and their exaggerated femininity and sexuality is used in a similar way to the title character's exaggerated masculinity, lampooning stereotypes.[27]

Sex objects

| Part of a series on |

| Sex and sexuality in speculative fiction |

|---|

Feminist critic Patricia Melzer writes in Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought that gynoids in Richard Calder's Dead Girls are inextricably linked to men's lust, and are mainly designed as sex-objects, having no use beyond "pleasing men's violent sexual desires".[29] The gynoid character Eve from the film Eve of Destruction has been described as "a literal sex bomb", with her subservience to patriarchal authority and a bomb in place of reproductive organs.[22] In the film The Perfect Women, the titular robot Olga is described as having "no sex", but Steve Chibnall writes in his essay "Alien Women" in British Science Fiction Cinema that it is clear from her fetishistic underwear that she is produced as a toy for men, with an "implicit fantasy of a fully compliant sex machine".[30] In the film West World, female robots actually engaged in intercourse with human men as part of the make-believe vacation world human customers paid to attend.

Sex with gynoids has been compared to necrophilia.[31] Sexual interest in gynoids and fembots has been attributed to fetishisation of technology, and compared to Sadomasochism in that it reorganizes the social risk of sex. The depiction of female robots minimizes the threat felt by men from female sexuality and allow the "erasure of any social interference in the spectator's erotic enjoyment of the image".[5] Gynoid fantasies are produced and collected by online communities centered around chat rooms and web-site galleries.[32]

Isaac Asimov writes that his robots were generally sexually neutral and that giving the majority masculine names was not an attempt to comment on gender. He first wrote about female-appearing robots at the request of editor Judy-Lynn del Rey.[33][34] Asimov's short story "Feminine Intuition" (1969) is an early example that showed gynoids as being as capable and versatile as male robots, with no sexual connotations.[35] Early models in "Feminine Intuition" were "female caricatures", used to highlight their human creators' reactions to the idea of female robots. Later models lost obviously feminine features, but retained "an air of femininity".[36]

No comments:

Post a Comment