Built and designed in the 1960s after the A-12 Oxcart, the SR-71 Blackbird is still the fastest, most vanguardist air-breathing airplane in the history of aviation.

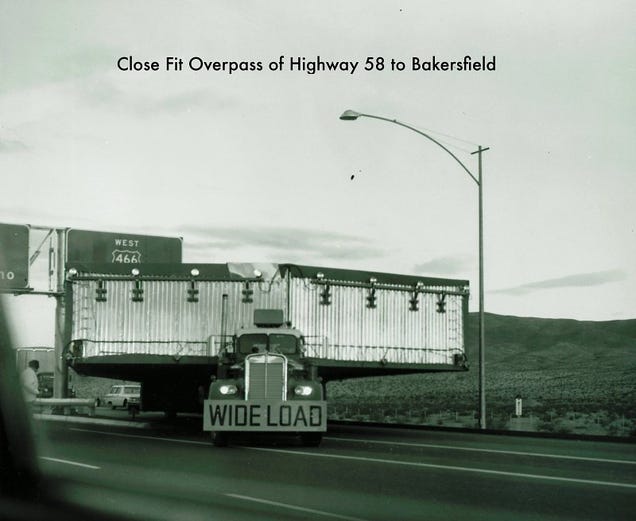

These once classified photos reveal how Lockheed built both birds in

secret, in California. They look taken at the Rebel base in Hoth.

"Everything had to be invented"

The A-12

and the SR-71 were a completely different design from anything else

before it—and everything after, as time has demonstrated. At the time,

many of the technologies needed to make these airplanes were considered

"impossible." And yet, thanks to Kelly Johnson and the amazing team at

engineers and scientists at Lockheed's Skunk Works, they were invented

from scratch—in twenty months.

According to Lockheed Martin's official account,

Kelly Johnson—the engineer who made the A-12 Oxcart and the SR-71

Blackbird—"everything had to be invented. Everything." From the The Pratt & Whitney J58 engines—a

technological feat still unsurpassed by today's mass manufactured

airplanes—to its titanium skin—capable of surviving temperatures from

315C (600F) to more than 482C (900F)—and composite materials. Its landing gear, for example, is "the largest piece of titanium ever forged in the world."

Ironically, the United States did not have enough titanium to build

these airplanes, so they have to buy it from the Soviet Union. Imagine

that: Buying the only material in the world that could make an spy plane

from the country you wanted to spy.

Major Brian Shul, one of the SR-71 pilots and author of Sled Driver, tells more about the manufacturing process:

Lockheed engineers used a titanium alloy to construct more than 90 percent of the SR-71, creating special tools and manufacturing procedures to hand-build each of the 40 planes. Special heat-resistant fuel, oil, and hydraulic fluids that would function at 85,000 feet and higher also had to be developed.

Thanks to

these technologies and his skills, Shul survived many surface-to-air

missile attacks (check out this amazing story about how the Blackbird saved his neck over the skies of Libya.) No Blackbird was ever shot down.

These photos are a testimony to this amazing engineering and manufacturing feat:

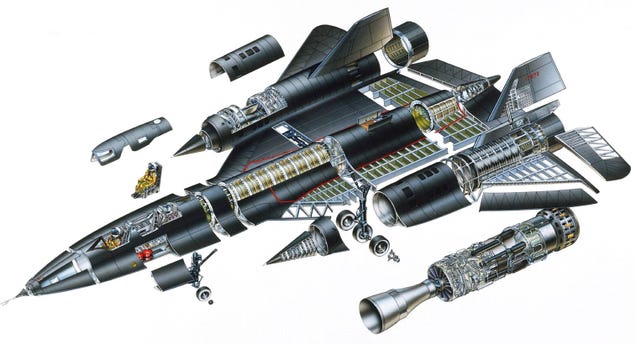

Cutaway illustrations of the twin cockpit variant of the SR-71.

Notice the inlet funnels that increased the air speed in front of the J58 engines.

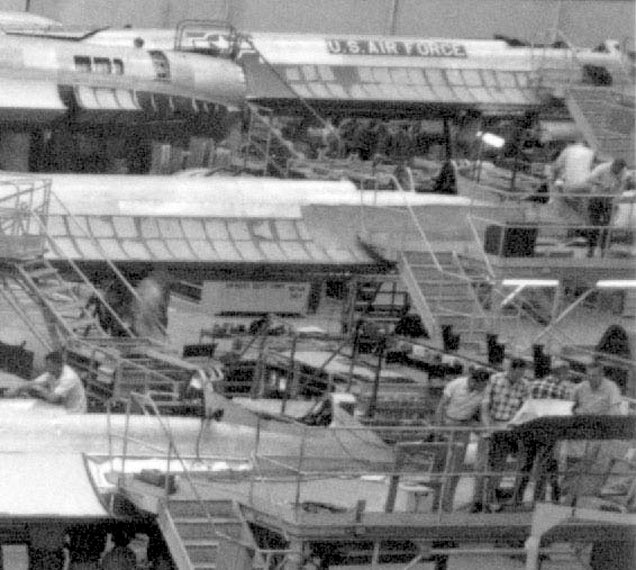

Lockheed's Skunk Works's manufacturing plant in Burbank, California. Later,

both the Oxcart and the Blackbird would be coated with an special black

paint that reduced the temperature by 23C (75F) and had radar absorbing

capabilities.

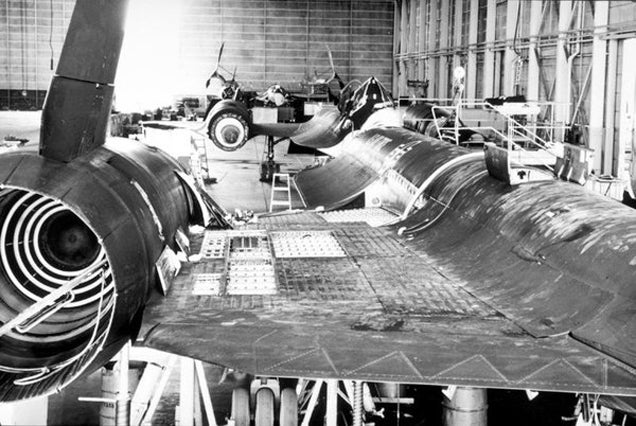

Notice the titanium panels forming the skin of these birds.

Only 50

Blackbird airframes were built. "The dies or molds were destroyed as

directed by then Secretary of Defense McNamara to prevent any other

nation from building the aircraft."

Final A-12 Oxcart ever produced: Article 133

Close up of one of the SR-71s in manufacturing

Another angle, from the other side

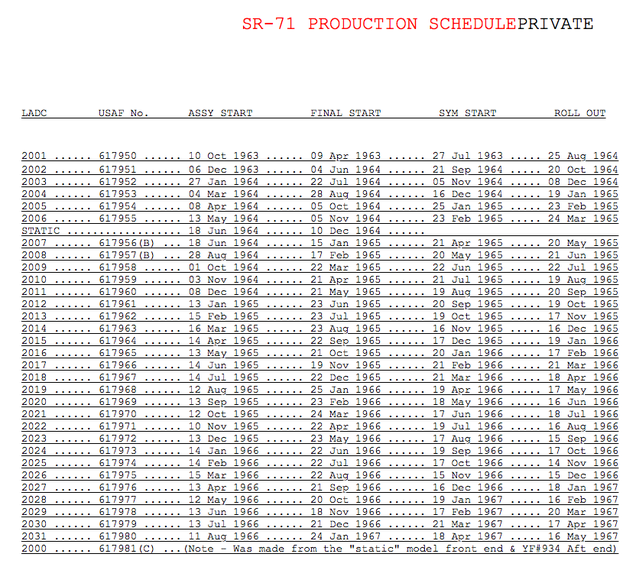

Production schedule for the SR-71

The J-58 engines

This is the exhaust of the J-58 engine. It could reach temperatures of 1760C (3200F).

The Blackbirds kept flying long after their retirement from the USAF. One of them stayed at NASA: Here's

a photo from the Armstrong Flight Research Center (then Dryden) of an

SR-71 being retrofitted for test of the Linear Aerospike SR Experiment

(LASRE).

The finished Blackbirds

And now more Blackbird porn because I know you love it

The analog

cockpit was the only thing that, compared to the

rest of futuristic

technologies used in the Oxcart and

Blackbird, seems completely out of

place:

You can see it in ultra-high definition here. And get the explanation of how it works from a SR-71 pilot here.

478 total people have flown the Blackbirds. More people have climbed to the top of Mount Everest than has flown this aircraft. Although a few Lockheed crewmembers were killed during the testing stages of the Blackbird, the U.S. Air Force never lost a man in the entire 25 years of active service. The SR-71 flew for 17 straight years (1972-1989) without a loss of plane or crew. Considering the environment the Blackbirds flew in, that is an enviable safety record.

According

to Kelly Johnson, no SR-71 was ever touched by any of the more than

1,000 missiles launched at these birds since its first mission to 1981.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(Redirected from Lockheed M-21)

Not to be confused with McDonnell Douglas A-12 Avenger II.

| A-12 | |

|---|---|

| An A-12 aircraft (serial number 06932) | |

| Role | High-altitude reconnaissance aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Corporation |

| First flight | 26 April 1962 |

| Introduction | 1967 |

| Retired | 1968 |

| Status | Retired |

| Primary user | Central Intelligence Agency |

| Number built | A-12: 13; M-21: 2 |

| Variants | Lockheed YF-12 |

| Developed into | Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird |

The Lockheed A-12 was a reconnaissance aircraft built for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) by Lockheed's famed Skunk Works, based on the designs of Clarence "Kelly" Johnson. The A-12 was produced from 1962 to 1964, and was in operation from 1963 until 1968. The single-seat design, which first flew in April 1962, was the precursor to both the twin-seat U.S. Air Force YF-12 prototype interceptor and the famous SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft. The aircraft's final mission was flown in May 1968, and the program and aircraft retired in June of that year. The A-12 program was officially revealed in the mid-1990s.[1]

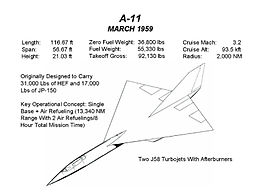

Design and development

With the failure of the CIA's Project Rainbow to reduce the radar cross section of the U-2, preliminary work began inside Lockheed in late 1957 to develop a follow-on aircraft to overfly the Soviet Union. Under Project Gusto the designs were nicknamed "Archangel", after the U-2 program, which had been known as "Angel". As the aircraft designs evolved and configuration changes occurred, the internal Lockheed designation changed from Archangel-1 to Archangel-2, and so on. These nicknames for the evolving designs soon simply became known as "A-1", "A-2", etc.[2]These designs had reached the A-11 stage when the program was reviewed. The A-11 was competing against a Convair proposal called Kingfish, of roughly similar performance. However, the Kingfish included a number of features that greatly reduced its radar cross section, which was seen as favorable to the board. Lockheed responded with a simple update of the A-11, adding twin canted fins instead of a single right-angle one, and adding a number of areas of non-metallic materials. This became the A-12 design. On 26 January 1960, the CIA ordered 12 A-12 aircraft.[3] After selection by the CIA, further design and production of the A-12 took place under the code-name Oxcart.

The first five A-12s, in 1962, were initially flown with Pratt & Whitney J75 engines capable of 17,000 lbf (76 kN) thrust each, enabling the J75-equipped A-12s to obtain speeds of approximately Mach 2.0. On 5 October 1962, with the newly developed J58 engines, an A-12 flew with one J75 engine, and one J58 engine. By early 1963, the A-12 was flying with J58 engines, and during 1963 these J58-equipped A-12s obtained speeds of Mach 3.2.[7] Also, in 1963, the program experienced its first loss when, on 24 May, "Article 123"[8] piloted by Kenneth S. Collins crashed near Wendover, Utah.[9]

The reaction to the crash illustrated the secrecy and importance of the project. The CIA called the aircraft a Republic F-105 Thunderchief as a cover story;[10] local law enforcement and a passing family were warned with "dire consequences" to keep quiet about the crash.[8] Each was also paid $25,000 in cash to do so; the project often used such cash payments to avoid outside inquiries into its operations.[8] The project received ample funding; contracted security guards were paid $1,000 monthly with free housing on base, and chefs from Las Vegas were available 24 hours a day for steak, Maine lobster, or other requests.[8]

In June 1964, the last A-12 was delivered to Groom Lake,[11] from where the fleet made a total of 2,850 test flights.[10] A total of 18 aircraft were built through the program's production run. Of these, 13 were A-12s, three were prototype YF-12A interceptors for the U.S. Air Force (not funded under the OXCART program), and two were M-21 reconnaissance drone carriers. One of the 13 A-12s was a dedicated trainer aircraft with a second seat, located behind the pilot and raised to permit the Instructor Pilot to see forward. The A-12 trainer "Titanium Goose", retained the J75 powerplants for its entire service life.[12]

Operational history

The Director of the CIA decided to deploy some A-12s to Asia. The first A-12 arrived at Kadena Air Base on Okinawa on 22 May 1967. With the arrival of two more aircraft on 24 May, and 27 May this unit was declared to be operational on 30 May, and it began Operation Black Shield on 31 May.[15] Mel Vojvodich flew the first Black Shield operation, over North Vietnam, photographing surface-to-air missile (SAM) sites, flying at 80,000 ft (24,000 m), and at about Mach 3.1. During 1967 from the Kadena Air Base, the A-12s carried out 22 sorties in support of the War in Vietnam. Then during 1968, Black Shield conducted operations in Vietnam and it also carried out sorties during the Pueblo Crisis with North Korea.[citation needed]

Retirement

Ronald L. Layton flew the 29th and final A-12 mission on 8 May 1968, over North Korea. On 4 June 1968, just 2½ weeks before the retirement of the entire A-12 fleet, an A-12 out of Kadena, piloted by Jack Weeks, was lost over the Pacific Ocean near the Philippines while conducting a functional check flight after the replacement of one of its engines.[17][18] Frank Murray made the final A-12 flight on 21 June 1968, to Palmdale, California storage facility.[19]

On 26 June 1968, Vice Admiral Rufus L. Taylor, the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence, presented the CIA Intelligence Star for valor to Weeks' widow and pilots Collins, Layton, Murray, Vojvodich, and Dennis B. Sullivan for participation in Black Shield.[17][20][21]

The deployed A-12s and the eight non-deployed aircraft were placed in storage at Palmdale. All surviving aircraft remained there for nearly 20 years before being sent to museums around the United States. On 20 January 2007, despite protests by Minnesota's legislature and volunteers who had maintained it in display condition, the A-12 preserved in Minneapolis, Minnesota, was dismantled to ship to CIA Headquarters to be displayed there.[22]

Timeline

The following timeline describes the overlap of the development and operation of the A-12, and the evolution of its successor, the SR-71.- 16 August 1956: Following Soviet protest of U-2 overflights, Richard M. Bissell, Jr. conducts the first meeting on reducing the radar cross section of the U-2. This evolves into Project Rainbow.

- December 1957: Lockheed begins designing subsonic stealthy aircraft under what will become Project Gusto.

- 24 December 1957: First J-58 engine run.

- 21 April 1958: Kelly Johnson makes first notes on a Mach 3 aircraft, initially called the U-3, but eventually evolving into Archangel I.

- November 1958: The Land panel provisionally selects Convair Fish (B-58-launched parasite) over Lockheed's A-3.

- June 1959: The Land panel provisionally selects Lockheed A-11 over Convair Fish. Both companies instructed to re-design their aircraft.

- 14 September 1959: CIA awards antiradar study, aerodynamic structural tests, and engineering designs, selecting Lockheed's A-12 over rival Convair's Kingfish. Project Oxcart established.

- 26 January 1960: CIA orders 12 A-12 aircraft.

- 1 May 1960: Francis Gary Powers is shot down in a U-2 over the Soviet Union.

- 26 April 1962: First flight of A-12 with Lockheed test pilot Louis Schalk at Groom Lake.

- 13 June 1962: SR-71 mock-up reviewed by USAF.

- 30 July 1962: J58 engine completes pre-flight testing.

- October 1962: A-12s first flown with J58 engines

- 28 December 1962: Lockheed signs contract to build six SR-71 aircraft.

- January 1963: A-12 fleet operating with J58 engines

- 24 May 1963: Loss of first A-12 (#60–6926)

- 20 July 1963: First mach 3 flight

- 7 August 1963: First flight of the YF-12A with Lockheed test pilot James Eastham at Groom Lake.

- June 1964: Last production A-12 delivered to Groom Lake.

- 25 July 1964: President Johnson makes public announcement of SR-71.

- 29 October 1964: SR-71 prototype (#61-7950) delivered to Palmdale.

- 22 December 1964: First flight of the SR-71 with Lockheed test pilot Bob Gilliland at AF Plant #42. First mated flight of the MD-21 with Lockheed test pilot Bill Park at Groom Lake.

- 28 December 1966: Decision to terminate A-12 program by June 1968.

- 31 May 1967: A-12s conduct Black Shield operations out of Kadena

- 3 November 1967: A-12 and SR-71 conduct a reconnaissance fly-off. Results were questionable.

- 26 January 1968: North Korea A-12 overflight by Jack Weeks photo-locates the captured USS Pueblo in Changjahwan Bay harbor.[23]

- 5 February 1968: Lockheed ordered to destroy A-12, YF-12 and SR-71 tooling.

- 8 March 1968: First SR-71A (#61-7978) arrives at Kadena AB to replace A-12s.

- 21 March 1968: First SR-71 (#61-7976) operational mission flown from Kadena AB over Vietnam.

- 8 May 1968: Jack Layton flies last operational A-12 sortie, over North Korea.

- 5 June 1968: Loss of last A-12 (#60–6932)

- 21 June 1968: Final A-12 flight to Palmdale, California.

Variants

Training variant

YF-12A

Main article: Lockheed YF-12

The YF-12 program was a limited production variant of the A-12.

Lockheed convinced the U.S. Air Force that an aircraft based on the A-12

would provide a less costly alternative to the recently canceled North

American Aviation XF-108,

since much of the design and development work on the YF-12 had already

been done and paid for. Thus, in 1960 the Air Force agreed to take the

seventh through ninth slots on the A-12 production line and have them

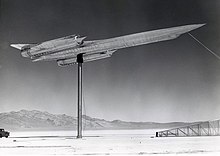

completed in the YF-12A interceptor configuration.[24]M-21

See also: Lockheed D-21

The M-21 variant carried and launched the Lockheed D-21,

an unmanned, faster and higher-flying reconnaissance drone. The M-21

had a pylon on its back for mounting the drone and a second cockpit for a

Launch Control Operator/Officer (LCO) in the place of the A-12's Q bay.[25]

The D-21 was autonomous; after launch, it would fly over the target,

travel to a predetermined rendezvous point, eject its data package, and

self-destruct. A C-130 Hercules would catch the package in midair.[26]The M-21 program was canceled in 1966 after a drone collided with the mother ship at launch. The crew ejected safely, but the LCO drowned when he landed in the ocean and his flight suit filled with water.[27] The D-21 lived on in the form of a B-model launched from a pylon under the wing of the B-52 bomber. The D-21B performed operational missions over China from 1969 to 1971.[28]

A-12 aircraft production and disposition

| Serial number | Model | Location or fate |

|---|---|---|

| 60-6924 | A-12 | Air Force Flight Test Center Museum Annex, Blackbird Airpark, at Plant 42, Palmdale, California. 606924 was the first A-12 to fly. |

| 60-6925 | A-12 | Intrepid Sea-Air-Space Museum, parked on the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid, New York City |

| 60-6926 | A-12 | Lost, 24 May 1963 |

| 60-6927 | A-12 | California Science Center in Los Angeles, California (Two-canopied trainer model, "Titanium Goose")[29] |

| 60-6928 | A-12 | Lost, 5 January 1967 |

| 60-6929 | A-12 | Lost, 28 December 1965 |

| 60-6930 | A-12 | U.S. Space and Rocket Center, Huntsville, Alabama |

| 60-6931 | A-12 | CIA Headquarters, Langley, Virginia[N 1] |

| 60-6932 | A-12 | Lost, 4 June 1968 |

| 60-6933 | A-12 | San Diego Aerospace Museum, Balboa Park, San Diego, California |

| 60-6937 | A-12 | Southern Museum of Flight, Birmingham, Alabama |

| 60-6938 | A-12 | Battleship Memorial Park (USS Alabama), Mobile, Alabama |

| 60-6939 | A-12 | Lost, 9 July 1964 |

| 60-6940 | M-21 | Museum of Flight, Seattle, Washington |

| 60-6941 | M-21 | Lost, 30 July 1966 |

Specifications (A-12)

General characteristics- Crew: 1 (2 for trainer variant)

- Length: 101.6 ft (30.97 m)

- Wingspan: 55.62 ft (16.95 m)

- Height: 18.45 ft (5.62 m)

- Wing area: 1,795 ft² (170 m²)

- Empty weight: 54,600 lb (24,800 kg)

- Loaded weight: 124,600 lb (56,500 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Pratt & Whitney J58-1 afterburning turbojets, 32,500 lbf (144 kN) each

- Payload: 2,500 lb (1,100 kg) of reconnaissance sensors

- Maximum speed: Mach 3.35 (2,210 mph, 3,560 km/h) at 75,000 ft (23,000 m)

- Range: 2,200 nmi (2,500 mi, 4,000 km)

- Service ceiling: 95,000 ft (29,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 11,800 ft/min (60 m/s)

- Wing loading: 65 lb/ft² (320 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.56

See also

- Related development

- Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Related lists

No comments:

Post a Comment