From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Simulated view of VentureStar in low Earth orbit | |||

| Function | Manned Re-usable Spaceplane |

|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Martin |

| Country of origin | United States |

| Size | |

| Height | 38.7 m[1] (127 ft) |

| Diameter | N/A |

| Mass | 1,000,000 kg[1] (2,200,000 lb) |

| Stages | 1 |

| Capacity | |

| Payload to LEO | 20,412 kg[1] (45,000 lb) |

| Launch history | |

| Status | Cancelled |

| Launch sites | Unknown |

| Total launches | 0 |

| First stage - VentureStar | |

| Engines | 7 RS2200 Linear Aerospikes[1] |

| Thrust | 3,010,000 lb[1] (13.39 MN) |

| Burn time | |

| Fuel | LOX/LH2[1] |

VentureStar was to be a single-stage-to-orbit vehicle, launching vertically but returning as an airplane. VentureStar was to be a commercial endeavor, and flights would have been leased to NASA as needed. After failures with the X-33 subscale technology demonstrator test vehicle, funding was cancelled in 2001.

Contents

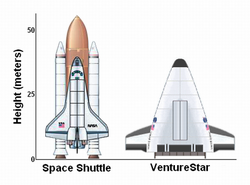

Advantages over the Space Shuttle

VentureStar's engineering and design had offered numerous advantages over the Space Shuttle, representing considerable savings in time and materials, as well as increased safety.[2] VentureStar was expected to launch satellites into orbit at about 1/10 the cost of the Shuttle.Readying VentureStar for flight would have dramatically differed from that of the Space Shuttle. Unlike the Space Shuttle orbiter, which had to be lifted and assembled together with several other heavy components (a large external tank, plus two solid rocket boosters), VentureStar was to be simply inspected in a hangar like an aeroplane.[2]

Also unlike the Space Shuttle, VentureStar would not have relied upon solid rocket boosters which had to be hauled out of the ocean and then refurbished after each launch.[2] Furthermore, design specifications called for the use of linear aerospike engines that maintain thrust efficiency at all altitudes. The Shuttle relied upon conventional nozzle engines which achieve maximum efficiency at only a certain altitude.[2]

VentureStar would have used a new metallic thermal protection system, safer and cheaper to maintain than the ceramic one used on the Space Shuttle. VentureStar's metallic heat shield would have eliminated 17,000 between-flight maintenance hours typically required to satisfactorily check (and replace if needed) the thousands of heat-resistant ceramic tiles that comprised the Shuttle exterior.[2]

VentureStar was expected to be safer than most modern rockets.[2] Whereas most modern rockets fail catastrophically when an engine fails during flight, VentureStar was intended to have a thrust reserve in each engine in the event of an emergency during flight.[2] For example, if an engine on VentureStar were to have failed during an ascent to orbit, another engine opposite to the failed engine would have shut off to counterbalance the failed thrust, and each of the remaining working engines could then have throttled up so as to safely continue the mission.[2]

VentureStar would have been environmentally clean.[2] Unlike the Space Shuttle, whose solid rocket boosters expended chemical wastes during launch, VentureStar's exhausts would have been composed of only water vapor, since VentureStar's main fuels would have been only liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen.[2] VentureStar's simpler design would have excluded hypergolic propellants and even hydraulics, instead only relying upon electrical power for flight controls, doors and landing gear.[2]

Because of its lighter design, VentureStar would have been able to land at virtually any major airport in an emergency,[2] whereas the Space Shuttle required much longer runways than publicly available.

No comments:

Post a Comment