From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Electromagnetism |

|---|

|

The first derivation of the Lorentz force is commonly attributed to Oliver Heaviside in 1889,[1] although other historians suggest an earlier origin in an 1865 paper by James Clerk Maxwell.[2] Hendrik Lorentz derived it a few years after Heaviside.[citation needed]

Contents

- 1 Equation (SI units)

- 2 History

- 3 Trajectories of particles due to the Lorentz force

- 4 Significance of the Lorentz force

- 5 Lorentz force law as the definition of E and B

- 6 Force on a current-carrying wire

- 7 EMF

- 8 Lorentz force and Faraday's law of induction

- 9 Lorentz force in terms of potentials

- 10 Lorentz force and analytical mechanics

- 11 Equation (cgs units)

- 12 Relativistic form of the Lorentz force

- 13 Applications

- 14 See also

- 15 Footnotes

- 16 References

- 17 External links

Equation (SI units)

See also: SI units

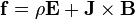

Charged particle

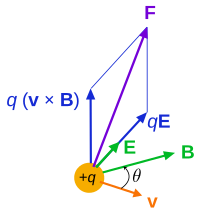

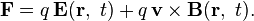

Lorentz force F on a charged particle (of charge q) in motion (instantaneous velocity v). The E field and B field vary in space and time.

A positively charged particle will be accelerated in the same linear orientation as the E field, but will curve perpendicularly to both the instantaneous velocity vector v and the B field according to the right-hand rule (in detail, if the thumb of the right hand points along v and the index finger along B, then the middle finger points along F).

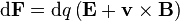

The term qE is called the electric force, while the term qv × B is called the magnetic force.[4] According to some definitions, the term "Lorentz force" refers specifically to the formula for the magnetic force,[5] with the total electromagnetic force (including the electric force) given some other (nonstandard) name. This article will not follow this nomenclature: In what follows, the term "Lorentz force" will refer only to the expression for the total force.

The magnetic force component of the Lorentz force manifests itself as the force that acts on a current-carrying wire in a magnetic field. In that context, it is also called the Laplace force.

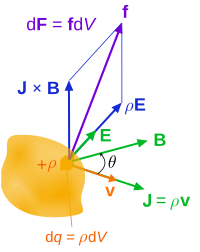

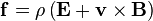

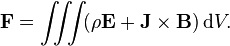

Continuous charge distribution

Lorentz force (per unit 3-volume) f on a continuous charge distribution (charge density ρ) in motion. The 3-current density J corresponds to the motion of the charge element dq in volume element dV and varies throughout the continuum.

In terms of σ and S, another way to write the Lorentz force (per unit 3d volume) is[6]

History

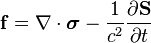

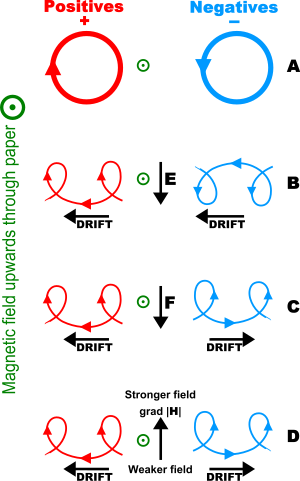

Trajectory of a particle with a positive or negative charge q under the influence of a magnetic field B, which is directed perpendicularly out of the screen.

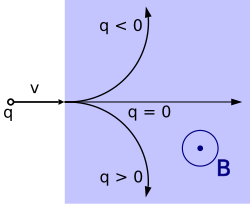

Beam of electrons moving in

a circle, due to the presence of a magnetic field. Purple light is

emitted along the electron path, due to the electrons colliding with gas

molecules in the bulb. Using a Teltron tube.

Charged particles experiencing the Lorentz force.

The modern concept of electric and magnetic fields first arose in the theories of Michael Faraday, particularly his idea of lines of force, later to be given full mathematical description by Lord Kelvin and James Clerk Maxwell.[11] From a modern perspective it is possible to identify in Maxwell's 1865 formulation of his field equations a form of the Lorentz force equation in relation to electric currents,[2] however, in the time of Maxwell it was not evident how his equations related to the forces on moving charged objects. J. J. Thomson was the first to attempt to derive from Maxwell's field equations the electromagnetic forces on a moving charged object in terms of the object's properties and external fields. Interested in determining the electromagnetic behavior of the charged particles in cathode rays, Thomson published a paper in 1881 wherein he gave the force on the particles due to an external magnetic field as[1]

Trajectories of particles due to the Lorentz force

Main article: Guiding center

Significance of the Lorentz force

While the modern Maxwell's equations describe how electrically charged particles and currents or moving charged particles give rise to electric and magnetic fields, the Lorentz force law completes that picture by describing the force acting on a moving point charge q in the presence of electromagnetic fields.[3][16] The Lorentz force law describes the effect of E and B upon a point charge, but such electromagnetic forces are not the entire picture. Charged particles are possibly coupled to other forces, notably gravity and nuclear forces. Thus, Maxwell's equations do not stand separate from other physical laws, but are coupled to them via the charge and current densities. The response of a point charge to the Lorentz law is one aspect; the generation of E and B by currents and charges is another.In real materials the Lorentz force is inadequate to describe the behavior of charged particles, both in principle and as a matter of computation. The charged particles in a material medium both respond to the E and B fields and generate these fields. Complex transport equations must be solved to determine the time and spatial response of charges, for example, the Boltzmann equation or the Fokker–Planck equation or the Navier–Stokes equations. For example, see magnetohydrodynamics, fluid dynamics, electrohydrodynamics, superconductivity, stellar evolution. An entire physical apparatus for dealing with these matters has developed. See for example, Green–Kubo relations and Green's function (many-body theory).

Lorentz force law as the definition of E and B

In many textbook treatments of classical electromagnetism, the Lorentz force Law is used as the definition of the electric and magnetic fields E and B.[17][18][19] To be specific, the Lorentz force is understood to be the following empirical statement:- The electromagnetic force F on a test charge at a given point and time is a certain function of its charge q and velocity v, which can be parameterized by exactly two vectors E and B, in the functional form:

Note also that as a definition of E and B, the Lorentz force is only a definition in principle because a real particle (as opposed to the hypothetical "test charge" of infinitesimally-small mass and charge) would generate its own finite E and B fields, which would alter the electromagnetic force that it experiences. In addition, if the charge experiences acceleration, as if forced into a curved trajectory by some external agency, it emits radiation that causes braking of its motion. See for example Bremsstrahlung and synchrotron light. These effects occur through both a direct effect (called the radiation reaction force) and indirectly (by affecting the motion of nearby charges and currents). Moreover, net force must include gravity, electroweak, and any other forces aside from electromagnetic force.

Force on a current-carrying wire

When a wire carrying an electrical current is placed in a magnetic field, each of the moving charges, which comprise the current, experiences the Lorentz force, and together they can create a macroscopic force on the wire (sometimes called the Laplace force). By combining the Lorentz force law above with the definition of electrical current, the following equation results, in the case of a straight, stationary wire:If the wire is not straight but curved, the force on it can be computed by applying this formula to each infinitesimal segment of wire dℓ, then adding up all these forces by integration. Formally, the net force on a stationary, rigid wire carrying a steady current I is

One application of this is Ampère's force law, which describes how two current-carrying wires can attract or repel each other, since each experiences a Lorentz force from the other's magnetic field. For more information, see the article: Ampère's force law.

EMF

The magnetic force (q v × B) component of the Lorentz force is responsible for motional electromotive force (or motional EMF), the phenomenon underlying many electrical generators. When a conductor is moved through a magnetic field, the magnetic force tries to push electrons through the wire, and this creates the EMF. The term "motional EMF" is applied to this phenomenon, since the EMF is due to the motion of the wire.In other electrical generators, the magnets move, while the conductors do not. In this case, the EMF is due to the electric force (qE) term in the Lorentz Force equation. The electric field in question is created by the changing magnetic field, resulting in an induced EMF, as described by the Maxwell–Faraday equation (one of the four modern Maxwell's equations).[21]

Both of these EMF's, despite their different origins, can be described by the same equation, namely, the EMF is the rate of change of magnetic flux through the wire. (This is Faraday's law of induction, see above.) Einstein's theory of special relativity was partially motivated by the desire to better understand this link between the two effects.[21] In fact, the electric and magnetic fields are different faces of the same electromagnetic field, and in moving from one inertial frame to another, the solenoidal vector field portion of the E-field can change in whole or in part to a B-field or vice versa.[22]

Lorentz force and Faraday's law of induction

Main article: Faraday's law of induction

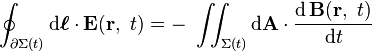

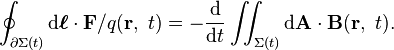

Given a loop of wire in a magnetic field, Faraday's law of induction states the induced electromotive force (EMF) in the wire is:The sign of the EMF is determined by Lenz's law. Note that this is valid for not only a stationary wire — but also for a moving wire.

From Faraday's law of induction (that is valid for a moving wire, for instance in a motor) and the Maxwell Equations, the Lorentz Force can be deduced. The reverse is also true, the Lorentz force and the Maxwell Equations can be used to derive the Faraday Law.

Let Σ(t) be the moving wire, moving together without rotation and with constant velocity v and Σ(t) be the internal surface of the wire. The EMF around the closed path ∂Σ(t) is given by:[23]

NB: Both dℓ and dA have a sign ambiguity; to get the correct sign, the right-hand rule is used, as explained in the article Kelvin-Stokes theorem.

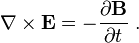

The above result can be compared with the version of Faraday's law of induction that appears in the modern Maxwell's equations, called here the Maxwell-Faraday equation:

So we have, the Maxwell Faraday equation:

If the magnetic field is fixed in time and the conducting loop moves through the field, the magnetic flux ΦB linking the loop can change in several ways. For example, if the B-field varies with position, and the loop moves to a location with different B-field, ΦB will change. Alternatively, if the loop changes orientation with respect to the B-field, the B • dA differential element will change because of the different angle between B and dA, also changing ΦB. As a third example, if a portion of the circuit is swept through a uniform, time-independent B-field, and another portion of the circuit is held stationary, the flux linking the entire closed circuit can change due to the shift in relative position of the circuit's component parts with time (surface ∂Σ(t) time-dependent). In all three cases, Faraday's law of induction then predicts the EMF generated by the change in ΦB.

Note that the Maxwell Faraday's equation implies that the Electric Field E is non conservative when the Magnetic Field B varies in time, and is not expressible as the gradient of a scalar field, and not subject to the gradient theorem since its rotational is not zero. See also.[23][25]

Lorentz force in terms of potentials

See also: Mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field, Maxwell's equations, and Helmholtz decomposition

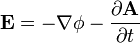

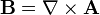

The E and B fields can be replaced by the magnetic vector potential A and (scalar) electrostatic potential ϕ byThe force becomes

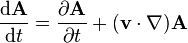

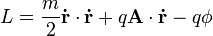

Lorentz force and analytical mechanics

See also: Momentum

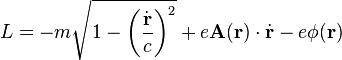

The Lagrangian for a charged particle of mass m and charge q in an electromagnetic field equivalently describes the dynamics of the particle in terms of its energy, rather than the force exerted on it. The classical expression is given by:[26][show]Derivation of Lorentz force from classical Lagrangian (SI units)

The relativistic Lagrangian is

[show]Derivation of Lorentz force from relativistic Lagrangian (SI units)

Equation (cgs units)

See also: cgs units

The above-mentioned formulae use SI units which are the most common among experimentalists, technicians, and engineers. In cgs-Gaussian units, which are somewhat more common among theoretical physicists, one has insteadRelativistic form of the Lorentz force

Covariant form of the Lorentz force

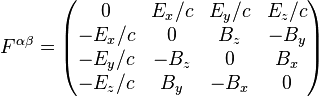

Field tensor

Main articles: Covariant formulation of classical electromagnetism and Mathematical descriptions of the electromagnetic field

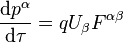

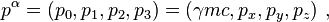

Using the metric signature (-1,1,1,1), The Lorentz force for a charge q can be written in covariant form: the proper time of the particle, Fαβ the contravariant electromagnetic tensor

the proper time of the particle, Fαβ the contravariant electromagnetic tensor is the Lorentz factor defined above.

is the Lorentz factor defined above.The fields are transformed to a frame moving with constant relative velocity by:

Translation to vector notation

The α = 1 component (x-component) of the force isSTA form of the Lorentz force

The electric and magnetic fields are dependent on the velocity of an observer, so the relativistic form of the Lorentz force law can best be exhibited starting from a coordinate-independent expression for the electromagnetic and magnetic fields,[27] , and an arbitrary time-direction,

, and an arbitrary time-direction,  , where

, where is a space-time bivector (an oriented plane segment, just like a vector

is an oriented line segment), which has six degrees of freedom

corresponding to boosts (rotations in space-time planes) and rotations

(rotations in space-space planes). The dot product with the vector

is a space-time bivector (an oriented plane segment, just like a vector

is an oriented line segment), which has six degrees of freedom

corresponding to boosts (rotations in space-time planes) and rotations

(rotations in space-space planes). The dot product with the vector  pulls a vector (in the space algebra) from the translational part,

while the wedge-product creates a trivector (in the space algebra) who

is dual to a vector which is the usual magnetic field vector. The

relativistic velocity is given by the (time-like) changes in a

time-position vector

pulls a vector (in the space algebra) from the translational part,

while the wedge-product creates a trivector (in the space algebra) who

is dual to a vector which is the usual magnetic field vector. The

relativistic velocity is given by the (time-like) changes in a

time-position vector  , where

, whereApplications

The Lorentz force occurs in many devices, including:- Cyclotrons and other circular path particle accelerators

- Mass spectrometers

- Velocity Filters

- Magnetrons

- Lorentz force velocimetry

![{\mathbf {F}}({\mathbf {r}},{\mathbf {{\dot {r}}}},t,q)=q[{\mathbf {E}}({\mathbf {r}},t)+{\mathbf {{\dot {r}}}}\times {\mathbf {B}}({\mathbf {r}},t)]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/b/0/5b00efe720a1eba71859b13377afbcd8.png)

![{\mathbf {F}}=q\left[-\nabla \phi -{\frac {\partial {\mathbf {A}}}{\partial t}}+{\mathbf {v}}\times (\nabla \times {\mathbf {A}})\right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/6/4/5/645ec37306a8ba39e3aa7cdd7317f663.png)

![{\mathbf {F}}=q\left[-\nabla \phi -{\frac {\partial {\mathbf {A}}}{\partial t}}+\nabla ({\mathbf {v}}\cdot {\mathbf {A}})-({\mathbf {v}}\cdot \nabla ){\mathbf {A}}\right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/b/b/5bba93090de1fda1fd2e66af09934f27.png)

![{\mathbf {F}}=q\left[-\nabla (\phi -{\mathbf {v}}\cdot {\mathbf {A}})-{\frac {d{\mathbf {A}}}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}\right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/0/9/409824050e9f9978d8e954b0fb479168.png)

![{\mathbf {F}}=q\left[-\nabla _{{{\mathbf {x}}}}(\phi -{\dot {{\mathbf {x}}}}\cdot {\mathbf {A}})+{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}}{{\mathrm {d}}t}}\nabla _{{{\dot {{\mathbf {x}}}}}}(\phi -{\dot {{\mathbf {x}}}}\cdot {\mathbf {A}})\right]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/a/a/c/aac235a2bb0cd59222be81d621f3c626.png)

![{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}p^{1}}{{\mathrm {d}}\tau }}=q\left[U_{0}\left({\frac {-E_{x}}{c}}\right)+U_{2}(B_{z})+U_{3}(-B_{y})\right].\,](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/d/3/9/d3922f69e3e8a6e81627fed0bc67a648.png)

![{\begin{aligned}{\frac {{\mathrm {d}}p^{1}}{{\mathrm {d}}\tau }}&=q\gamma \left[-c\left({\frac {-E_{x}}{c}}\right)+u_{y}B_{z}+u_{z}(-B_{y})\right]\\&=q\gamma \left(E_{x}+u_{y}B_{z}-u_{z}B_{y}\right)\\&=q\gamma \left[E_{x}+\left({\mathbf {u}}\times {\mathbf {B}}\right)_{x}\right]\,.\end{aligned}}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/5/0/5/5052b1ad14772834e5623d0b0cda7d54.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment